Magical Thinking and Cultural Amnesia on the Western Frontier

Board games encourage a form of magical thinking, in which a small rectangle of cardboard becomes an inhabitable space with ample scope for movement and action. One of the most expansive spaces evoked in such games has been the American West, especially in the postwar period, when manufacturers capitalized on the popularity of television Westerns, issuing games such as Hopalong Cassidy and Gunsmoke. Yet the phenomenon has a longer history. The Lone Ranger Game was produced in 1938, and the Bandit Trail Game Featuring Gene Autry in 1929. The Game of Buffalo Bill is even older, dating from the last years of the 19th century, when the western frontier stood at the center of contemporary debates about the future of white America.

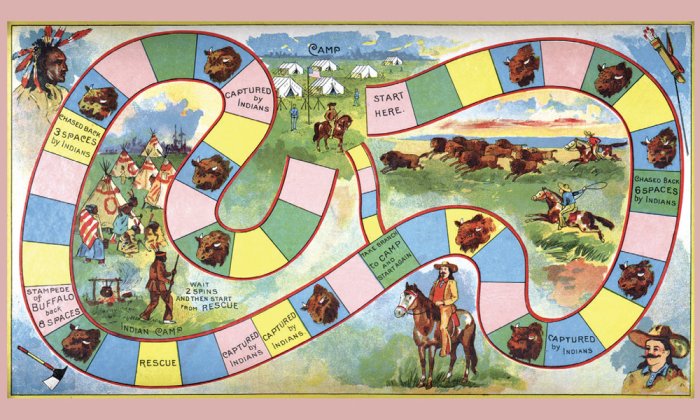

Parker Brothers issued The Game of Buffalo Bill, in which players emulate the famous bison hunter William F. Cody, in 1898. The year of the game’s release is noteworthy, as just five years earlier, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner had bemoaned the closing of the frontier, which he argued was integral to giving American democracy its particular form and spirit. Via Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows, which ran from 1884 to 1913, Cody kept the frontier open for his urban audiences, staging spectacles of Western dangers — including Indian attacks on settler cabins — calculated to provide a vicarious thrill. Perhaps The Game of Buffalo Bill could bring a similar frontier-by-proxy experience into the middle-class parlor, a site many late-19th-century critics associated with doting mothers and milquetoast sons.

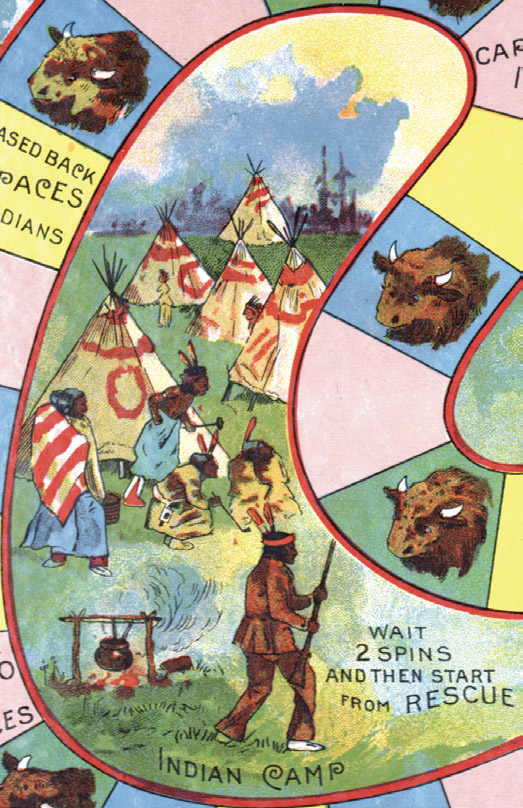

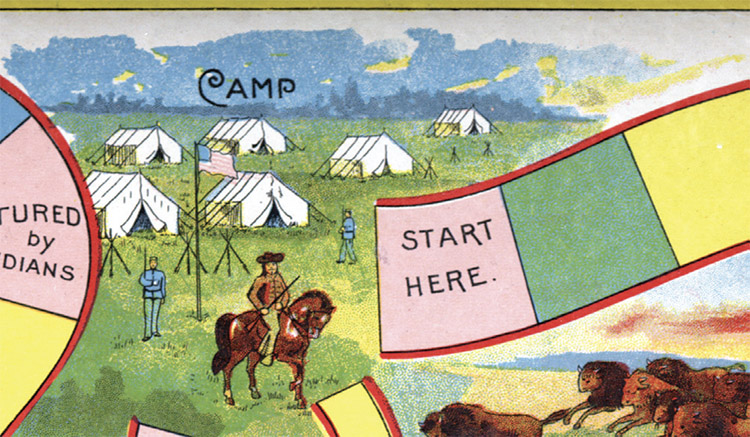

To be sure, the racial logic of the game parallels that of Turner’s Frontier Thesis and the Wild West shows. The players — the ones enjoying agency in the game — are implicitly white. They start and finish the game at the “Camp,” a label without a racial modifier, as whiteness here is the unmarked norm. Visual cues help convey the racial identity of the site, where an American flag flutters over rows of military-style tents facing a parade ground guarded by armed white men. The whiteness of this locale is confirmed by the presence of an “Indian Camp” in another vignette. (Of course, “Native American” had not yet entered the lexicon, but the word “Indian” was anything but value-free; whites often used it interchangeably with “savage.”)

Although the Indian camp, too, is guarded by a man with a rifle, everything else about it highlights the differences between the two settings and their human inhabitants: the irregular arrangement of colorful tepees, the figures’ hunched postures, the blankets in which some of them are wrapped, and the feathers that others wear in their headbands. Tellingly, the Indian camp is not a site of agency; when players land on a space labeled “captured by Indians,” they move their playing piece to the Indian camp, where the game board instructs them to “wait 2 spins and then start from [the space labeled] Rescue.” Indeed, there are four spaces where players can be “captured by Indians,” two others where they can be “chased back 6 spaces by Indians,” and just one where they confront a buffalo stampede. In short, Indians are the primary impediment to a successful hunt.

At the same time, The Game of Buffalo Bill is remarkably tame. For one thing, the object of the game is to capture at least 10 buffalo before beating a hasty return to camp. Cody, of course, did not capture buffalo; he killed them. He purportedly killed over 4,000 in an eight-month period in 1867 and 1868 and even nicknamed his rifle “Lucretia Borgia” in acknowledgment of the gun’s alluring deadliness. Yet, in the game’s vignette of the hunt, the white hunters are unarmed. (One swings a lasso in an improbable attempt to rope a galloping buffalo.) Even being captured by Indians is a sedate affair. The seized player simply sits out two turns, certain in the knowledge of rescue; how or by whom is not specified. The game’s sinuous path — its form undoubtedly meant to suggest the uncultivated character of the landscape — would not be out of place in a Picturesque garden. Even the game board’s pastel color palette seems calculated to allay any sense of danger. Yes, two of the game board’s corners contain images of Native American weapons, but even these are displayed as trophies, material proof that white Americans had subdued the continent’s original inhabitants.

William Cody purportedly killed 4,000 buffalo in an eight-month period. Yet, in the game’s vignette of the hunt, the white hunters are unarmed.

Inevitability is endemic to The Game of Buffalo Bill, as in many board games. An indicator tells players how many spaces to move, ultimately determining the victor. While players may not know at the start of the game who will win, they can rest assured that one of their number, always imagined as white, will return to camp unscathed, having laid claim to the land by seizing control of its resources. In that sense, the indicator is like the deity who (in the minds of many white Americans) dictated that the nation’s manifest destiny was to occupy the continent from coast to coast.

If The Game of Buffalo Bill was a pallid version of the frontier experience Turner had valued so highly, it may have contributed something even more integral to normalizing white domination of North America. By inviting players to inhabit an imaginary space where frontier conflict was reduced to a gentle stroll along a pastel-colored path, this board game encouraged a form of magical thinking that amounted to a deep cultural amnesia about the violence — including the racial violence — inherent in the taking of the continent.

Abigail A. Van Slyck is Dayton Professor Emerita of Art History at Connecticut College. Her books include “A Manufactured Wilderness: Summer Camps and the Shaping of American Youth, 1890–1960” (University of Minnesota Press) and “Free to All: Carnegie Libraries and American Culture, 1890–1920” (University of Chicago Press). This article is excerpted from the volume “Playing Place.”