How to Perform the City in Poetry

On April 18, 1923, after having excoriated American artists, citizens, and law enforcement for more than a decade, the German-born Dadaist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874–1927) was leaving New York. Waving farewell from the Port Authority pier was magazine editor Jane Heap, who had steadfastly championed the Baroness’s poetry in the pages of The Little Review. The water churning beneath the S.S. York that was carrying the Baroness back to Germany was nothing compared to the violent turbulences she had whirled up during her thirteen-year sojourn in America.

No one had ever before seen a woman like the Baroness. In 1910, on arrival from Berlin, she was promptly arrested for promenading on Pittsburgh’s Fifth Avenue dressed in a man’s suit and smoking a cigarette, even garnering a headline in the New York Times: “She Wore Men’s Clothes,” it proclaimed aghast. Just as they were by her appearance, Americans were flabbergasted by the Baroness’s verse. Delirious in its ragged edges and atonal rhythms, the poetry echoes the noise of the metropolis itself. Profanity sounds loudly throughout her poems as she imagines a farting god; depicts sexless nuns gliding machine-like on wheels through city streets; and playfully deconstructs the names of her contemporaries, as Marcel Duchamp becomes “M’ars” (my arse) and William Carlos Williams is renamed “W.C.” (water closet).

As a neurasthenic, kleptomaniac, and man-chasing protopunk poet, the Baroness was an agent provocateur within New York’s modernist revolution. Together with the writers associated with Others magazine, including Alfred Kreymborg, William C. Williams, Ezra Pound, Hart Crane, Mina Loy, Wallace Stevens, and Lola Ridge, she was part of the free verse movement causing a public uproar “as much by the sexual content of the ‘corsetless verse’ as by its formal improprieties,” as Suzanne Churchill notes in her book “The Little Magazine Others and the Renovation of Modern American Poetry.” But the Baroness’s poetic enterprise, in advance even of the vanguard, involved more than taking off the proverbial corset — though she did that too by literalizing and performing the metaphor, infamously parading herself in the nude or in Dada couture of her own making.

The Baroness’s poetic practice, which both electrified and alienated other poets, courted danger and scandal by raising an entirely new set of questions: What constitutes poetry? What are its aims? Where are its borders? Steeped in the arts and crafts movement in Munich and Berlin, the Baroness embraced a do-it-yourself aesthetic that would become central to the punk movement sixty years later. Her poems are both antihierarchical and instructional, showing readers how to “do it yourself”: How to practice poetry in the modern world; how to become poetry; how to turn poetry into sex; and, fundamentally, how to use poetry to extend modern identity.

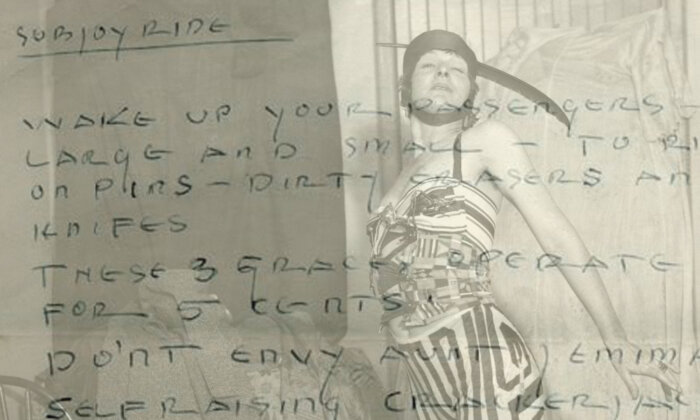

So how exactly does one make a performance poem in the modern world? The Baroness leads the way, cruising the city with her senses attuned to the language of the body. Take “Subjoyride,” in which we embark on a high-energy walk through New York City, board a subway car at Broadway, and traverse a museum city of readymades and objects trouvés. “Subjoyride” exuberantly channels the city’s unceasing motion and energy, but also forces us to confront the underside of a burgeoning culture of consumerism. With objects, brand names, and landmarks colliding, the poem draws attention to its very construction. It references the external world and mirrors the way in which the modern metropolis assaults our senses with electric signs, with scents and sounds, and supersized advertisements:

Wrigley’s

Pinaud’s heels for the wise —

Nothing so Pepsodent — soothing —

Pussy Willow — kept clean

With Philadelphia Cream

Cheese.

The Baroness is an associative machine whose finely tuned sensors find poetry in everyday life: appropriating, borrowing, cataloging, collaging, and parodying consumer products and advertisement slogans. Similar to Schwitters’ MERZ, a spoof on the pervasive dominance of KomMERZ or commerce, so the Baroness’s “Subjoyride” presents a form of Dada “subvertising.” Brand names are powerful precisely because they have the ability to change the cognitive structure of consumers, as Mark Batey notes in his book “Brand Meaning,” each encounter with a brand providing “a stimulus that is stored in the brain and adds to the associative network already existing for the brand.” The Baroness’s verse is fresh today because it lambasts the brand-centricity that shapes urbanite identities, a phenomenon more pervasive today than ever before (see Naomi Klein’s “No Logo”). Blasting our blasé attitude, our blinkered, self-involved consumption, the Baroness’s verse achieves one of Dada’s central goals: to deautomatize (deautomatisieren) the reader by defamiliarizing the quotidian familiar; to “Wake up your passengers—/Large and small,” as she writes in the poem.

Thus, we also experience poetry itself anew. Not by normative means pretty, the poems depict a life lived in desperation and in courage, and so are startling in their beauty. Our consciousness is captured not only by the baffling simultaneity of heterogeneous materials but by the ongoing transformation of self.

SUBJOYRIDE

READY-TO-WEAR —

AMERICAN SOUL POETRY.

(THE RIGHT KIND)

It’s popular — spitting Maillard’s

Safety controller handle —

You like it!

They actually kill Paris

Garters dromedary fragrance

Of C.N. in a big Yuban!

Ah — madam —

That is a secret Pep-O-Mint —

Will you try it —

To the last drop?

Tootsie kisses Marshall’s

Kippered health affinity

4 out of 5 — after 40 — many

Before your teeth full-o’

Pep with 10 nuggets products

Lighted Chiclets wheels and

Axels — carrying Royal

Lux Kamel hands off the

Better Bologna’s beauty —

Get this straight — Wrigley’s

Pinaud’s heels for the wise —

Nothing so Pepsodent — soothing —

Pussy Willow — kept clean

With Philadelphia Cream

Cheese.

They satisfy the man of

Largest mustard underwear —

No dosing —

Just rub it on.

Weak — rundown man like

The growing miss as well —

Getting on and off unlawful

With jelly — jam — or Meyer’s 100

Soap noodles

The Rubberset kind abounds —

The exact flavor lasts —

No metal can VapoRub

Oysterettes.

Wenatchee Barbasol peaks

Father John’s patent — presentation —

Set — cold — gum’s start

And finish.

18 years’ electro-pneumatic

Operation Mary Garden cost

The golden key $1,500,000

Smile — see Lee Union — all

It’s the grandest thing —

After every meal — no boiling

Required — keeps the

Doctor a day — just Musterole

Dear Mary — the mint with

The hole — oh Lifebuoy!

Adheres well — delights

Your taste — continuous

Germicidal action — it

Means a wealth of family

Vicks —

Our men know their

Combatant jobs since 1888 —

Quicker than Maxwell

Brakes.

You can teach a select

Seal packer parrot — Rinso —

Postum lister World-War

On Saxo Salve — —

Try a venotonic semi-

Soft of a stiff indigestion

Don’t scratch!

Original sunshine makes

Tanlac children

Do you know that made

From rich pure shaving

Cream Jim Henry tired 102

Out?

Famous Fain reduces

Reg’lar fellows to the

Toughest Cory Chrome

Pancake apparel — kept

Antiseptic with gold dust

Rapid transit — —

It has raised 3 generations

Of mince-piston-rings-pie.

Wake up your passengers —

Large and small — to ride

On pins — dirty erasers and

Knives

These 3 Graces operate slot

For 5 cents.

Don’t envy Aunt Jemima’s

Self raising Cracker Jack

Laxative knitted chemise

With that chocolaty

Taste — use Pickles in Pattern

Follow Green Lions.

(1920–1922)

Irene Gammel is Director of the Modern Literature and Culture Research Centreat Ryerson University, Toronto. She is the author of several books, including “Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity,” the first biography of the enigmatic dadaist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. You can engage her on twitter @MLC_Research.

Suzanne Zelazo is a poet, editor, and educator. She is the author of “Lances All Alike” and co-editor, with Irene Gammel, of “Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.”