Leonard Cohen and the Concert That Never Was

In late 2016, one week after the death of Leonard Cohen on November 7, 2016, I traveled to Ramallah to give a series of talks. As chance would have it, Michael Rakowitz was also there to give some artist-led workshops. Michael and I had been avowed fans of Cohen’s work for some time and we had discussed it at numerous events over the years. Apart from the sadness at his demise, there was a gratifying sense of what Cohen had left behind, in his music and writing, and we duly decided to hold an impromptu wake in the Garage Bar in Ramallah. Cohen’s songs were sung and others joined in — and, looking back now, it seemed a fitting way to celebrate the life of an artist we not only admired but had, in different ways, looked to for solace over the years.

Although we had both spoken of a project that Michael had been working on for some years, it was on that evening that I fully learned of its entire history. “I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze,” the title being a line from a Cohen song, had begun as a research project in 2009 and, by 2016, it was taking on a more coherent, and yet highly speculative form. From its outset, the project was focused on Leonard Cohen’s work and Michael would return to Ramallah in 2017, as he recounts below, to shoot a film in the Alhambra Palace Hotel that directly references a number of key events in the singer’s life. Two distinct elements arose here, one relating to a concert that Cohen performed on September 24, 2009, when he was booked to play at the Ramat Gan Stadium — the national stadium of Israel until 2014 — in the district of Tel Aviv. Following mounting pressure from pro-Palestinian voices, it was decided that the concert, his first in Israel since 1980, would be accompanied by a twin event at the Ramallah Cultural Palace in the West Bank. Hosted by the Palestinian Prisoners Club (PPC), this latter performance would be attended by families of some of the Palestinians in Israeli jails and detention centers. For various reasons, as we will see, the concert did not take place and Cohen never played in the West Bank, or anywhere else in Palestine — an omission that Michael’s project has since attempted to remedy.

The history of Cohen’s performances in the Middle East does not stop there and include an unlikely meeting between the singer and Ariel Sharon, then a major general in the Israeli army, in the Sinai desert during the 1973 Arab–Israeli War. As I became more aware of the project, both on the evening in question and over the last three years, I was more impressed at how Michael’s project distilled historical research, personal reflection, archival enquiry, performative gestures, exhibition making, epistolary dispatches, and other forms of informal communication to keep the project focused. In doing so, his research brought together seemingly disparate events including the formation of PACBI in Ramallah in 2004 (a founding member of the Palestinian Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions National Committee, also known as BDS); Cohen’s statements on Israel and Palestine (e.g., on the night of the Ramat Gan concert he declared his support for the Israeli-Palestinian NGO Bereaved Families for Peace movement); and a 2009 Leonard Cohen concert in Chicago that had an equally revelatory and disquieting impact on Rakowitz, who attended it with his wife, Lori; and, crucially, the concert that never happened in Ramallah. These approaches to research form a speculative understanding of, amongst other things, what constitutes authorship, cultural property, identity, material agency, evidence, political alliance, and the idea (if not ideal) of posthumous authorization, not to mention the legal issues surrounding the politics of boycotting.

The one abiding sense of the work that I have come away with is the idea of future potential: Out of a double refusal, the cancellation of Cohen’s concert and the difficulties encountered in staging Rakowitz’s program, there remains a recuperative gesture — embodied in Rakowitz’s goal to stage the concert through an act of radical cross-border ventriloquy — to this project that probes the conditions of possibility and impossibility in the name of solidarity. Conjoining the cultural histories of Palestine and Israel with the ethical dilemmas faced by performers under the conditions of a boycott, the project, and the accompanying volume, brings to light the research that went into this multifaceted work and plots the future arc of its trajectory. In the following interview, which is published in extended form in the book, I spoke to Michael about the historical origins of “I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze” and its many variations, including a number of elements that were abandoned as it was developed over time.

Anthony Downey: I want to begin by asking you how you first came across the multifaceted story that is at the center of this work: a story that involves, on the most simplistic level, a concert in Ramallah by the late Leonard Cohen that never took place. How did that begin?

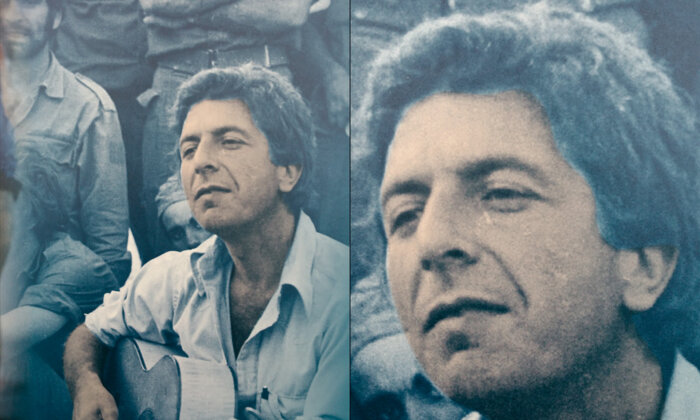

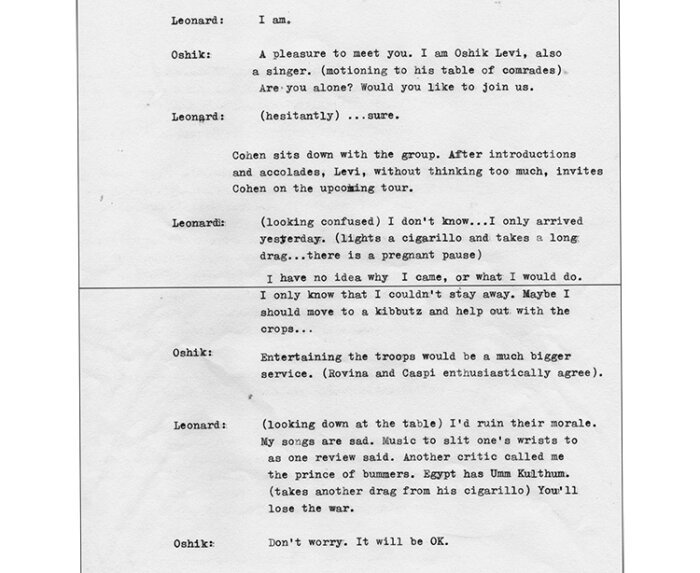

Michael Rakowitz: The project has multiple points of origin, which is appropriate since it is about — to use Cohen’s terms — “various positions,” and it is also about a multitude of different truths. The actual project probably has its most immediate origins in May 2009, on the night I saw Leonard Cohen at the Chicago Theatre, and in July of the same year, when a Cohen concert was canceled in Ramallah. My wife is a Montreal Jew, like Cohen (we met while dancing in the Bulgarian Bar in New York City in 2002), and we had gotten tickets from her parents for her birthday that year to see Cohen in concert […] What happened in that show was that a man approaching eighty years old – namely, Cohen – walked out with his group of musicians that included Javier Mas playing an archlute, which is a lot like an oud. […] When Cohen recited “A Thousand Kisses Deep” like a poem and said the line “I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze,” I felt like I was going to weep. As someone who deals with depression, it hit my core; as somebody who deals with my own disappointment or inability to do anything but stay in the middle and be frozen in between, those lines went straight to my most innermost self. Cohen’s economy of words, his being able to distill the human condition down to that one sentence, was phenomenal. After the concert, I was wired; I couldn’t sleep. I went to one of the Leonard Cohen online forums and there was a post with the subject line “Leonard Cohen, October 22, 1973,” which is the date I was born. I clicked on the post and it was an image of Cohen playing to Israeli soldiers in the Sinai desert, and in the crowd surrounding him was Ariel Sharon.

When Cohen recited “A Thousand Kisses Deep” like a poem and said the line “I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze,” I felt like I was going to weep. As someone who deals with depression, it hit my core.

For me, somebody who in 2009 had already been a signatory of the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) for three years, and had been critical of Zionism as an ideology that purports to speak for world Jewry and as an ideal to which we are supposed to adhere, the Zionist ideology of people like Sharon was something that I had long ago divested myself from. So, seeing my newfound idol sitting next to Sharon, who is like the symbol of everything that has gone wrong (in terms of Jewish nationalism, the displacement of people, and the genocide being waged against the Palestinian people), on the receiving end of Cohen’s art put me into a state of panic. What does this mean and why did it happen exactly on my birthday? An image of Cohen entering the stage appeared in my mind, not just onto the stage of the Chicago Theatre but also into my life, and then into my art life—and then that image was gone.

AD: What replaced that image of him?

MR: A much more complicated one. I felt that maybe this photograph is the image of the ethical crisis of the post-Holocaust Jew. I read more and more about why he was apparently in Israel that day, and I realized that it came out of a set of complicated moments in his life: his marriage was not going well, he had a young child that he didn’t know what to do with, and he wanted to leave Hydra, where he had been living with them. And then when he does leave, in October 1973, he goes to join the Jewish people who are facing (in that moment) their most serious existential threat—after the Holocaust—from Egypt and other countries. He left Hydra to go to Israel to, in his words, “stop Egypt’s bullet.” As a Jew, as somebody raised by an Iraqi Jewish mother, I had grown up as the child of parents who were born before the end of the Second World War and understood what its aftermath meant. This feeling, this cognitive dissonance, created a desire for a homeland for the Jewish people, which made so much sense in light of the millennia of racism and anti-Semitism that they had faced – a situation that culminated in the most horrific, systematic attempt to exterminate an entire race of people. I could understand where Cohen stood, and his feelings of doubt and unease. In that moment, for me, that discomfort Cohen feels made me realize that a film needs to be made: a film that describes our current condition.

AD: What happened then? Because things developed quickly for you in relation to this project.

MR: Well, based on the events described in Ira B. Nadel’s book Various Positions: A Life of Leonard Cohen (1996), and the whole incredible story of Cohen in Israel as a kind of warrior poet during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, my immediate thought was that those episodes should be conveyed not as a set of drawings but as a film. My friend, the photographer Marc Joseph Berg, looks a lot like Leonard Cohen and plays guitar, and so I immediately envisioned him being able to play that role. After learning about the history behind the photograph, I felt I already had a script for what could be a dynamic, complex, poetic, and surreal film based on the 1973 events alone.

However, two months after seeing Cohen in Chicago in 2009, I went to Jerusalem at the invitation of Jack Persekian, Director of the Al Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art. When I arrived, there was a rumor that Cohen was going to play in Ramallah in September of that year. That sounded incredible to me and I wondered what he had to go through to bring a concert to Ramallah. I wondered if he had second thoughts – those same second thoughts that I and other Jews have had – about his previous stance on Israel, as evidenced in his participation in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, and if playing in Ramallah was an articulation of this shift in his thinking. I started to think about the many times I have seen Cohen’s lyrics quoted – in writings about art by Palestinian artists such as Sharif Waked, for example. One of the first times I heard Cohen’s songs used in a soundtrack was in Palestinian director Elia Suleiman’s 1996 film, Chronicle of a Disappearance, where “First We Take Manhattan” is played, the first track on his 1988 album, I’m Your Man. The opening lyrics – “They sentenced me to twenty years of boredom / For trying to change the system from within” – are in many ways prophetic, but they suggest he has read the mind of every artist who has ever been conflicted about making a work of art in a system they find to be abhorrent yet continues to work inside that very system.

While I was in Jerusalem, a more complex story started to emerge. It was revealed that the Ramallah concert was being set up by Cohen’s management after the announcement of a gig that I didn’t know about, one scheduled for Tel Aviv on September 24, 2009. In Palestine, the perception was that the Ramallah concert was being pursued as a way of mitigating ongoing protests and potential protests leading up to and after the Tel Aviv concert. Cohen has a strong following in the Arab world so a concert in Ramallah would make sense, but in this case it was seen by Palestinian civil society as an attempt to please both the oppressor and the oppressed.

Cohen has a strong following in the Arab world so a concert in Ramallah would make sense, but in this case it was seen by Palestinian civil society as an attempt to please both the oppressor and the oppressed.

The actual story goes something like this: After Amnesty International pulled its association with the concert in Tel Aviv, Cohen’s management reached out to the Palestinian Prisoners Club (PPC) to see if they could work together and have him perform at the Ramallah Cultural Palace. The entire proceeds of the concert would be donated to the PPC to aid the plight of Palestinians in Israeli jails. I am still researching the details of this, so we will see what the research reveals at a later date. But the known outcome of all of this is that the PACBI raised opposition to the Ramallah concert if Cohen was still going to play Tel Aviv. Spokespeople for PACBI and Cohen engaged in dialogue, but ultimately the singer’s management needed to make a choice and decided to go ahead with the concert in Tel Aviv.

Thereafter, PACBI released several statements explaining their position on the matter in relation to the outcome. Cohen’s concert was then billed as “A Concert for Peace, Reconciliation and Tolerance,” with the proceeds donated to an organization that supports grassroots peacemaking efforts between Israeli and Palestinian families who have suffered loss as a result of the war. For me, these events identify a moment when I started to realize that one of the things that happens during a boycott is tragedy—and it has to happen because otherwise what is a boycott? Clearly, I was imagining the other possible outcome: the cancellation of the concert in Tel Aviv and how that would have been a different tragic outcome for Cohen and his Israeli fans. But, to put it in Jewish terms, a Yom Kippur fast is not supposed to be easy. I have signed on to a collective boycott, which I regard as being like a fast—an enactment of penitence, of meditation, of sorrow. But fasting is also like a boycott: it is (hopefully) temporary and will be broken so we can eat together again. At the same time, it was not lost on me that one of the potential costs of a boycott is that it can appear to be a moment where politics obliterates art. I wanted to find a way for art to obliterate politics. There was something about the fate of the artwork, in the midst of all this, that I wanted to meditate on.

AD: How did you go about effecting that—the sense of what happened to the artwork, in this instance, the unperformed concert?

MR: I started to think that maybe, as an artist who adheres to the terms of PACBI, I could perform that unfulfilled concert in Palestine. And in this sense, it is not so different than an orchestra performing the work of a composer from centuries ago. Cohen’s songs are not very hard to sing, they are not in a vocal register like Paul McCartney’s, which I cannot reach, so then I started to think, Well, maybe I could sing his songs.

AD: And there was a specific Cohen track that gave you a breakthrough on this, I recall.

MR: Cohen has this beautiful song called “Going Home,” from the 2012 album Old Ideas. When you listen to that song, it’s this wonderfully solipsistic thing where he’s saying: “I’d love to speak with Leonard / […] / Though he knows he’s really nothing / But the brief elaboration of a tube.”

AD: Ah yes, there is a thing here about tubes and venting, or giving voice, enunciating, but also deferral.

If Cohen is not allowed to enunciate the air coming from his lungs and sing in Ramallah, what would that mean if the air was coming from my anti-Zionist, Arab Jewish lungs?

MR: Yes, when I heard that I started to think about my old artworks with tubes, where I used air-conditioning and heating ventilation systems in projects like paraSITE (1998–ongoing); the warm air that goes through these custom-built shelters for the homeless is, by extension, inflating a pair of lungs. And the way that the voice is basically air that comes from our lungs and is then enunciated by the vocal cords. And I thought, Oh my god, this is all about air again! and if Cohen is not allowed to enunciate the air coming from his lungs and sing in Ramallah, what would that mean if the air was coming from my anti-Zionist, Arab Jewish lungs? Could I sing his songs? Would the elaboration of that tube be okay in enunciating and articulating and uttering his words? And that was where I got this idea to more or less do the concert and bring something into being where the art was recuperated, even if the art needed to be given over to somebody else who was actually able to carry it out. It’s a way of creating a double alliance, a double solidarity, and I was very interested in that because it complicates our thinking and widens our possibilities while creating a moment of vision where we can actually move forward together, as opposed to saying that we are frozen in the middle. I would be a surrogate, a host, to create an acceptable provenance from which to transmit the artwork. I was just really captivated by that: the work could still be a film but then this idea allowed me to enter into that photograph of Cohen singing in the Sinai desert on the day that I was born and to see the concert as something that truly relates to the Arab-Israeli War and the war within ourselves, which then becomes an artwork of atonement in some ways.

AD: You were asked to exhibit the work in 2015. Can you talk a little about that? Because it affects certain elements of the research and how the work developed.

MR: Yes, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MACM) found out about my project in 2015. They had written to me saying they were planning an exhibition called “The Future,” which was meant to celebrate the 375th anniversary of Montreal, and they had chosen Cohen as the artist that they wanted other artists to react to and focus on. The curators said that this was not being set up as a tribute to Cohen, because Cohen was not interested in simple beatification, but as an opportunity for other artists to respond to Cohen’s work. When they found out about my project, they thought it was important to include. I explained to them that the artwork is very much about wrestling with your angels, so to speak, which is considered something that is fundamental to Jewish thinking and debate. I thought: Oh my god, this is incredible, Cohen has actually given his blessing to the exhibition, which means he’s actually given his blessing to the project, and maybe I will even be able to meet this person who will give me permission to sing the concert in Ramallah and it’s going to be amazing.

[…]

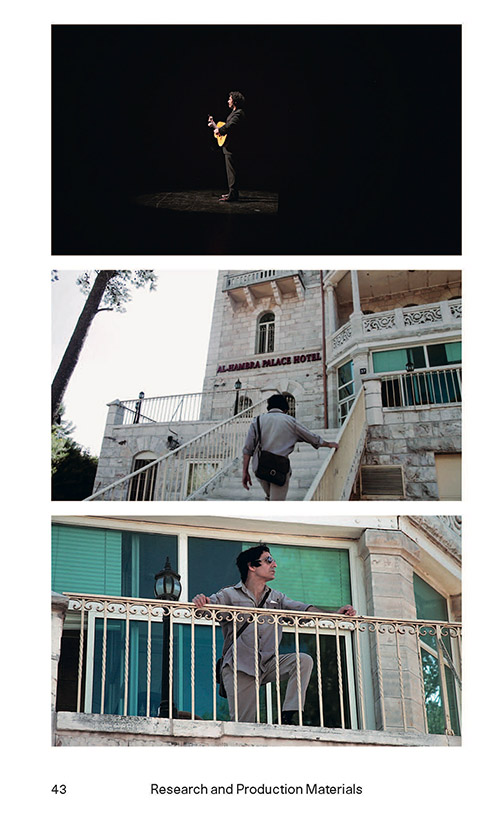

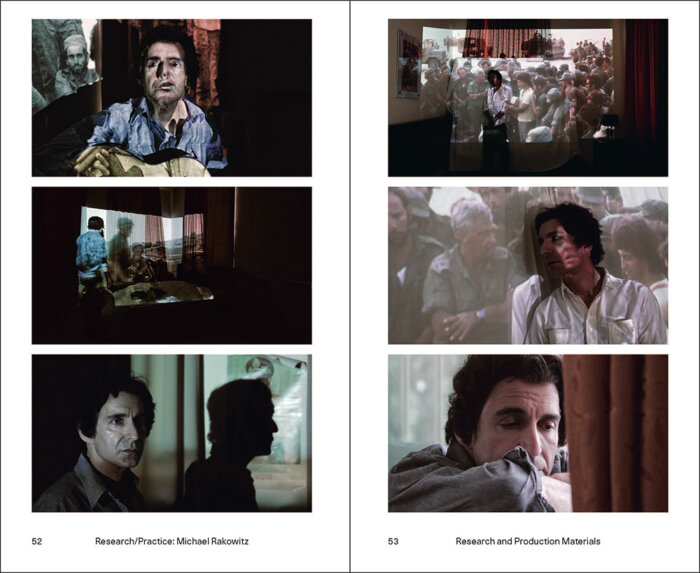

I had initial phone calls with Cohen’s manager and he was warm and interested, and loved the idea of the Ramallah concert happening, that is, with me singing the songs. And then I ended up in Ramallah to actually shoot the film in the Alhambra Palace Hotel in 2017. The Alhambra hotel was built as a private residence in 1926 and converted into a hotel in 1947. It was one of those hotels where popular singers, actors, and entertainers from the Arab world would stay if they were performing in places like Jerusalem. I considered that an interesting corollary. Originally, I thought that the Chelsea Hotel in New York City was the right site to make the film, since Cohen lived there for some time along with other great artists and performers, and immortalized the residence in his song “Chelsea Hotel #2.” Hotels in general have always seemed like surreal, liminal spaces to me, and I thought it would be beautifully abstract to film the events of October 1973 in that space. I dreamed up scenes of Leonard walking from his hotel room to the one across the hall to represent the Israelis crossing into Egypt during the war. Footage of the Arab-Israeli War would be projected on curtains in the room, bringing the battle into a personal space. But when I found out that the Alhambra also hosted celebrated performers at a time right before the partition of Palestine, it became much more interesting to film there. Choosing the Alhambra Palace Hotel as a site would allow Cohen to not just exist in this destination, but that he could step out of that place and into the limbo of Palestine, the “in between” space.

Hotels in general have always seemed like surreal, liminal spaces to me, and I thought it would be beautifully abstract to film the events of October 1973 in that space.

So in August 2017 Robert Chase Heishman, with whom I codirected the film, Marc Joseph Berg, who would be portraying Leonard Cohen, and I arrived in Ramallah, ready to film over a two-week period. While we were there I was contacted by the MACM. It seemed there was a misunderstanding of my initial proposal by Cohen’s management, who was surprised that an actor would be portraying his late client. This was concerning, since that had been part of the proposal since 2009. I did not think that there would be any conceptual or political disagreement with the work, since I was telling the story as I understood it to have happened and as it had been written about in Ira B. Nadel’s biography, Various Positions, which was unauthorized by the singer but was supposedly factual. And so, in this sense, I felt my project should proceed full speed ahead, but suddenly there seemed to be some turbulence.

In the midst of all this, I had been in contact with musicians in Palestine who expressed a willingness to play Cohen’s songs at the Ramallah Cultural Palace, where the concert was supposed to happen. This was all arranged with help from Jack Persekian and the Al Ma’mal Foundation, and there was enthusiasm about wielding art as something that could productively sidestep the boycott without punishing the artists. It was also a way for me to reconvene with my desire to become a better guitar player. When I started to gear up the project, I became so excited that I was taking flamenco guitar lessons every week—Cohen had also taken flamenco guitar lessons as a young man and some of his songs, such as “The Partisan” and “Avalanche,” have interesting and very challenging flamenco arpeggios. It was method art-making, like method acting, when you assume the behavior and life of the character you are going to depict in a role, and I started to feel closer to Cohen.

AD: But something else happened at this point?

MR: In prepping for all of this, and in running the first rehearsals for the concert—which was due to happen in October 2017 and would serve as the culmination of the film—it was revealed that the Palestinian musicians did not feel comfortable with the whole setup after all. Even though there was admiration for the songs, there was also resentment about who Cohen was, and those photographs of him playing for the Israeli army in 1973 had actually gone viral in the aftermath of his death. Media outlets in Israel started to circulate the photographs as a way of mourning Cohen and being thankful for the fact that he belonged to Israel. And so this created a moment of precarity for the musicians; they weren’t looking to abandon me, but they felt unsafe playing his songs and had to withdraw. This put an end to the idea of the concert being performed in Ramallah. (Add to this the fact that claims started to emerge—and I don’t know how much of this was verified—that Cohen’s songs had been used to torture Palestinian prisoners, and the situation became quite difficult. This had been reported on a website called Walla, using testimonies from Israeli soldiers.)

It was also clear that the interviews I had conducted and hoped to use in the film could not be used now. One of them was with Cohen’s management telling the story about the concert in Ramallah (how it happened, how it got canceled), and one with Omar Barghouti (who is one of the founders of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement and PACBI), telling it from his perspective. Barghouti was one of the people involved in the discussions around Cohen not being allowed to play in Ramallah so he offered to do an interview, which was very gracious of him. He finally disallowed its use in the documentary when he found out the Israeli consulate in Montreal had supported travel costs for one of the exhibiting artists to install work and attend the opening. I understood why that was a problem for Barghouti and I agreed with his decision. But if I wasn’t able to have his voice in the film then I wasn’t going to allow other voices to be there unchallenged. In a way, this project about refusal has effectively setup all these other refusals. So with the concert unable to happen, and for reasons I couldn’t predict at the time, it felt like the Cohen estate and the musicians were almost relieved that it wouldn’t happen. I still keep my fingernails long on my left hand—my strumming hand—so that if a miracle does happen, and it is decided that the show can be staged, then I can do it in a heartbeat. I practice the songs frequently, and continue to study the lyrics.

AD: I want to ask how, as an artist—and this is core to some of the questions this work raises—you can negotiate the apparent impasse of the rhetoric that surrounds pro-Israel/anti-Israel, pro-Zionist/anti-Zionist, and so on. Because it seems to me that you did find a way, a very productive, speculative way to do this. And that’s through a moment of ventriloquism: you ventriloquize Cohen, not to bypass a boycott (which would go against your long-held beliefs on this matter), but to reify the potential of a boycott to open up a further series of questions and debates around the relationship between politics and art, in both Cohen’s work and your own. What must not happen in order for something to happen? A concert must be canceled for a concert to potentially happen, and so on. Your concert was not performed because of the boycott that also stopped Cohen’s work from being performed, but your work—as a result of this double refusal—articulates a potential strategy that recuperates Cohen through your Arab Jewish ventriloquizing of his voice; something does happen from a series of refusals that creates a space of enunciation—does that make sense?

MR: Yes, of course. That’s a very beautiful way of putting it, and I thought about ventriloquy quite a lot, because it contains the word “vent,” which means wind, but of course the vent in ventriloquy is the belly, and the belly is connected to the diaphragm. The lungs enable enunciation, and the projection of the voice is like magic. I closed the film I made with a rendition of Cohen’s song “If It Be Your Will,” which includes the phrase “I shall abide until I am spoken for.” So if you want me to sing, I will sing; if you do not want me to sing, the act of not singing is a choice too. Nonparticipation is a choice, and sometimes not going forward is the thing to do. So, this song is really about voice, and the potential for words to be uttered but also the potential for words to be held in a place of indeterminacy, a space of limbo, just like the film as it currently stands, or the figure of Cohen in the Alhambra hotel. The precision that I am looking for is in the imprecise and the more ambiguous, which is the language of poetry. It’s not sloganeering.

In my work I hope to never engage in something as simplistic as sloganeering. I don’t think it necessarily makes great art, and that is ultimately what I am trying to do.

In my work I hope to never engage in something as simplistic as sloganeering. I don’t think it necessarily makes great art, and that is ultimately what I am trying to do. I think that that’s part of a way of using the impasse as material. In realizing that there are absences and redactions that point to a certain presence, but also accepting that such presence can be spectral. I talk about it all the time, with the things that I make that are engaging with the cultural heritage of Iraq: the spectral, ghostlike quality of the material. What I’m making is not a reconstruction, it is actually a reappearance—and it will disappear again. And that’s what a ghost does. I’m interested in art that can actually haunt. And to create these moments of discomfort that come in through comfort and intimacy.

Michael Rakowitz lives and works in Chicago. His work has appeared in venues worldwide including dOCUMENTA (13), P.S.1, MoMA, MassMOCA, Castello di Rivoli, the 16th Biennale of Sydney, the 10th and 14th Istanbul Biennial, Sharjah Biennial 8, Tirana Biennale, National Design Triennial at the Cooper-Hewitt, and Transmediale 05.

Anthony Downey is Professor of Visual Culture in the Middle East and North Africa, within the Faculty of Arts, Design and Media at Birmingham City University. He is the series editor for Research/Practice, published by Sternberg Press, and the author of several books on the politics of visual culture