‘It’s very likely you won’t be electrocuted’: On Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik’s ‘TV Bra’

On September 7, 1968, 100 members of the New York Radical Women gathered on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, New Jersey. They had come to picket the Miss America pageant to protest female enslavement to what they called “ludicrous beauty standards.”

The rally had a playful spirit. Stink bombs were thrown, a goat was crowned Miss America and paraded outside the convention hall, and a large bathing-beauty puppet was auctioned off. At the center of the action was a “Freedom Trash Can” into which the women tossed the implements of their enslavement: high-heeled shoes, girdles, false eyelashes, hair curlers, and brassieres. “Liberation now!” they shouted. The organizers had intended to set the trash afire, but they did not, calling the action instead “a symbolic bra-burning.”

The composer and video artist Nam June Paik had a nose for the absurd, especially when it concerned sex, women, pop culture, and mass media. Within months of the purported bra-burning he had devised a new piece for Charlotte Moorman, “TV Bra for Living Sculpture” (1969). No Maidenform, Paik’s bra was an ungainly assemblage of two small television picture tubes encased in plexiglass boxes, one for each breast, which were held on Moorman’s body by wide, transparent vinyl straps and safety pins. It was uncomfortable — she complained about its weight (nearly six pounds) and the heat it generated — and she worried about the high-voltage wires attached to the backs of its picture tubes, which carried between five and ten thousand volts of electricity over her bare skin. When Paik strapped her in for the first time, he said, “It’s very likely you won’t be electrocuted.”

There were several options for its operation. The TV sets could be tuned to broadcast television or display prerecorded tapes; they could also show a live, closed-circuit image captured by Paik as he walked among the audience with a video camera. (“Putting the audience’s faces on my brassiere,” was Moorman’s description of this method.) When Moorman wore “TV Bra” she improvised what she called abstract sounds on her cello and altered the television pictures in various ways. Sometimes she taped magnets to her wrists, which distorted the video images as she moved her arms; other times, she used a microphone to pick up the cello sounds, which were then transformed into optical signals that disturbed the television pictures.

Moorman debuted the piece on May 17, 1969, in a five-hour performance at the opening of the exhibition “TV as a Creative Medium,” organized by Howard Wise for his gallery on West 57th Street. By all accounts it was a dazzling show, with two darkened rooms of TV sets that glowed with kaleidoscopic colors and abstract video fantasies. The sight of her in that gallery of unmanned machines must have been startling. Bathed in the eerie glow of cathode-ray tubes, she and her cello were an earthy oasis of flesh, hair, sweat, wood, and catgut. The “TV Bra,” by contrast, comprised a pair of electronic pasties that streamed intangible, almost magical energy. Together these two aspects transformed Moorman into a female shaman for the McLuhan age, an era when technological gadgets were not the ubiquitous bodily prostheses that they are today.

According to its title, “TV Bra” was made for a “living sculpture.” Was Paik thinking of himself as Pygmalion, the mythic sculptor who fell so deeply in love with his statue that the gods brought her to life? Perhaps; he had once described topless Moorman as a “live Greek female torso sitting still at a cello.” But during the 1960s, the concept of a “living sculpture” was in vogue among artists aiming to confuse the boundaries of art, life, and commerce. Early in the decade the Italian artist Piero Manzoni had sold “magic bases,” portable pedestals that turned anyone who stood on them into a human sculpture. For a fee, he would also sign your body and issue a certificate declaring you a work of art. In 1962, during the Festival of Misfits, the French artist Ben Vautier lived for three weeks in the storefront window of London’s Gallery One as a “Living Sculpture” who could be purchased for 250 pounds. And in 1969, the British collaborative team Gilbert and George coated themselves with bronze paint and stood motionless for a time on a staircase in a Dutch museum.

“TV Bra” belongs to this aesthetic species, but its central theme was the link between human beings and their machines. “The real issue implied in [the fusion of] ‘Art and Technology,’” Paik wrote in the Wise Gallery exhibition brochure, “is not to make another scientific toy, but how to humanize technology and the electronic medium, which is progressing rapidly — too rapidly.” In “TV Bra” he accomplished this through a doubling in which Moorman’s body became a television screen and televisions stood in for parts of her body.

While “TV Bra” was a serious work of art, it was also a send-up — of bra-burnings, “Living Bras” (a then-current ad slogan for Playtex brassieres), and widespread worries that excessive time in front of the “boob tube” was breeding an infantile population addicted to “electronic breastfeeding.” Moorman expanded the parody by making it her habit to don the bra onstage, as part of the performance. Because it was too heavy and awkward to put on by herself, she always had an assistant, usually male. This resulted in an unlikely vignette: a man laboring to help a woman put on her bra rather than take it off. (At the Wise Gallery exhibition her assistant was Paik’s teenaged nephew Ken Hakuta. He remembers that Moorman’s breasts were the first he had ever seen, and that Paik “threw an absolute fit” when he found out what had transpired.)

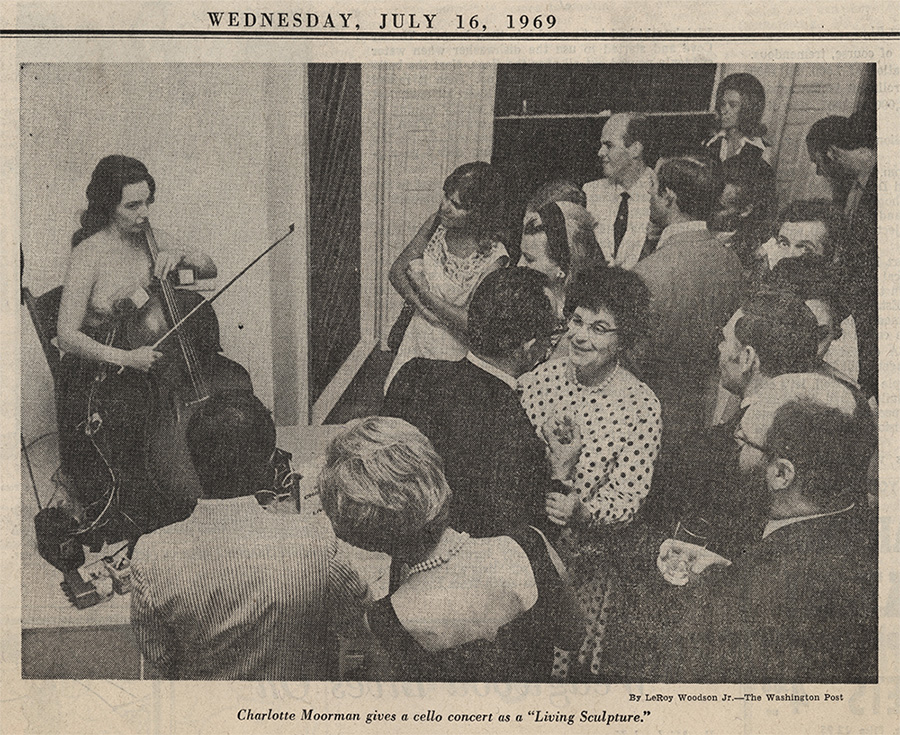

In July 1969, Moorman took “TV Bra” to Washington, D.C., for the opening of the Corcoran Gallery’s “Cybernetic Serendipity,” another of the growing number of exhibitions to explore the conjunction of communication, science, and art. The cocktail party preview was on July 16, the day that Apollo 11 was launched on its historic moon-landing mission. Moorman performed that evening and later wrote to New York Times critic Grace Glueck about the experience: “I’m so sorry I couldn’t stop performing Paik’s TV Bra to speak to you before you left. But I was performing for the most marvelous cross-section of people — computer experts, men who build missiles, mothers and their children, NBC and Metro Media TV, Popular Photography magazine, artists, tourists, etc. — with the space takeoff program on each breast. They asked such things as what I thought the future of TV and art is? How my TV Bra worked mechanically? What is the connection of the space flight and my TV Bra? etc. I always play so they can see the whole work, but afterwards I’m happy to answer their questions.” Whenever Moorman wore the “TV Bra,” she became her own tour guide. She peppered her performances with explanatory chat and sometimes even answered questions while she was playing. She was earthy, approachable, and charming. “Like a hostess at a Texas barbeque,” recalls one viewer.

“TV Bra” was the first new work Paik made for Moorman after her arrest two years earlier. Clearly it was a response to that incident; “TV Bra” both restored her modesty and relieved her of the designation “topless.” (Never mind that the bra actually encouraged prurience by compelling spectators to stare at her breasts.) More broadly, “TV Bra” was the culmination of Moorman and Paik’s five-year-long project to conjoin sex and music. As an object, it perfectly encapsulates Paik’s artistic goals, Moorman’s brilliance as a performer, their personal history, and its cultural context. In hindsight, “TV Bra” almost seems inevitable.

“‘TV Bra’ is one third of [the piece], I’m one third of it, and my cello is one third of it. When we’re all together, the work is complete.”

Moorman adored the piece. She believed it was Paik’s finest work and said that wearing it was “a great, great feeling, so pure and romantic.” During the 1970s she performed “TV Bra” more than any other piece in her repertoire, so much so that it became an attribute nearly equal in importance to her cello. When she became too ill to use it any longer, she put it on a shelf in her loft, and she and her husband Frank watched the David Letterman Show on its tiny sets. Only when she was near death and desperately in need of cash did she agree to sell it.

“TV Bra” initiated the second phase of Moorman and Paik’s relationship, and for that alone it would be notable. It also is a signal work in the history of video art, an unprecedented fusion of sculpture, moving imagery, performance, sound, and popular culture. Without Moorman’s body, spirit, and cello, however, it is considerably diminished. As she put it, “‘TV Bra’ is one third of [the piece], I’m one third of it, and my cello is one third of it. When we’re all together, the work is complete.”

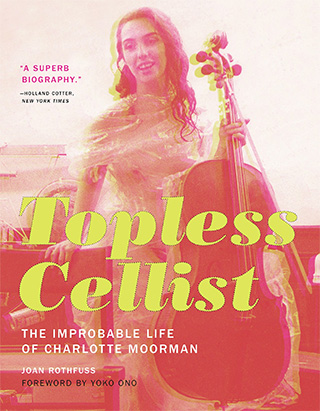

Joan Rothfuss is an independent writer and curator based in Minneapolis. From 1988 to 2006 she was a curator at the Walker Art Center, where she organized exhibitions on Joseph Beuys, Bruce Conner, Jasper Johns, and Fluxus, among others. Her many publications include the books “Time Is Not Even, Space Is Not Empty: Eiko & Koma” (Walker Art Center, 2011) and “Topless Cellist: The Improbable Life of Charlotte Moorman,” from which this article is excerpted.