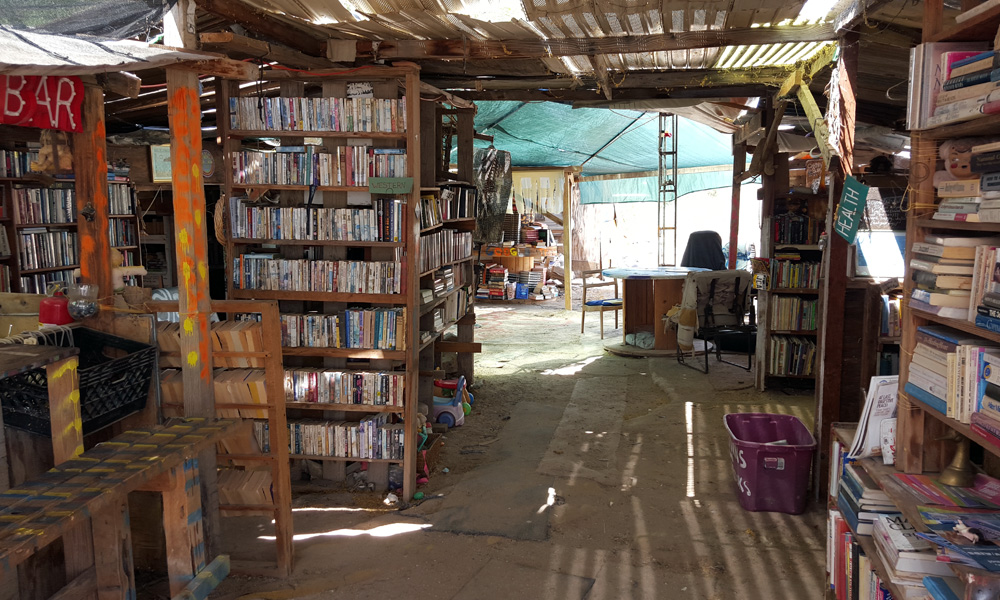

Inside the Lizard Tree Library at Slab City

Under the unforgiving sun of southern California’s Colorado Desert lies Slab City, a community of squatters, artists, snowbirds, migrants, survivalists, and homeless people. Called by some “the last free place” and by others “an enclave of anarchy,” Slab City is also the end of the road for many. Without official electricity, running water, sewers, or trash pickup, Slab City dwellers also live without law enforcement, taxation, or administration. Built on the concrete slabs of Camp Dunlap, an abandoned Marine training base, the settlement maintains its off-grid aspirations within the site’s residual military perimeters and gridded street layout; off-grid is really in-grid.

In their book “Slab City: Dispatches from the Last Free Place,” from which the following text is excerpted, architect and writer Charlie Hailey and photographer Donovan Wylie explore the contradictions of Slab City. They show us Slab Mart, a conflation of rubbish heap and recycling center; RVs in conditions ranging from luxuriously roadworthy to immobile; shelters cloaked in pallets and palm fronds; and the alarmingly opaque water of the hot springs.

Editor’s note: The Lizard Tree Library reached out in August 2024 to clarify that the library is now under the care of Head Librarian Zoe Aurora Grimes and does, in fact, close. Please check their hours before visiting.

Suspense fills Lizard Tree Library’s anteroom. Romance is in the cubby to its side. Midday sun blows in through the door frame, and its crisp ambience illuminates the gold and aqua cover of Kate Mosse’s bestseller “Labyrinth,” the spine of Tess Gerritsen’s “Body Double,” Patricia Cornwell’s “All That Remains,” and what looks to be Ann Rule’s entire true-crime oeuvre. With the desert sun, you enter through the narrow frame, stooping and stepping down five inches, just enough to know that you have arrived. There’s no door because the library never closes. Carpet lines a lumpy floor, and dirt and bottle caps pool in low spots and well up where it meets plywood walls. Splintered and bleeding creosote, railroad ties turn upright to support a roof draped with woven and dyed fabric that hangs only a few inches above six feet.

Sitting on an L-shaped bench, an intimate corner within the foyer’s refuge, your eyes adjust to saturated light, as cardboard labels on mattress springs wave genres, desperate for attention in shade-cooled wind. It’s all here: zines to science, biography to biology, history to sci fi, homeschooling to parenting. Above plywood and particle board shelves and a section labeled Large Print, another message sends notice: Shut up and read. That recess to your left is the Romance section, red hearts painted on shelves, and incongruously, but actually just right, a ripped Arnold Schwarzenegger posters the ceiling. A hardcover edition of “The Bridges of Madison County” lies open on the lowest shelf. Peggy Sadlik, known as Rosalie, started the library in 1999 with these two small rooms, six feet deep and about 16 across.

Cave Man and Cornelius Vanga set out to restore the library two and a half years ago. It had fallen into disrepair over the previous eight years, and the partners expanded its spaces and holdings fourfold beyond the original rooms. In the middle of the main area, a blue bin labeled Returns catalogs the circulation of recent titles; on top of a large pile are “Toad on the Road,” the April 2016 issue of Time magazine with Ted Cruz on the cover, and “The Tactical Edge: Surviving High Risk Patrol.” This library, like Slab City, is a place of juxtapositions. I turn around from the plastic box and pull a copy of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” from the Classics section.

Back on the bench, I read: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” García Márquez’s first lines remind me of the push and pull of time, and the gypsy camp a little further on is a lesson in the artifice of making do. Useful things presented to Buendia’s father — magnetized ingots, a telescope, and ice — become magical through their extraordinary properties. What if the equation is reversed? Books in Slab City are like ice in Macondo, and their stories — infused with lo real maravilloso — provide valuable footholds out here in the desert on the edge of society. As I read, the drone of the canal’s nearby falls is more muffled air than turbid water, and the curling edge of a book scratches against another’s cover. Palo verde flowers rattle in cobwebs and blow across floors, shelves, and books. The eponymous lizard tree is shedding its confetti of blossoms, faded yellow like exposed pages under the ceiling’s parted canvas skylights. García Márquez famously said that “surrealism runs through the streets” of Mexico, and the uncanny is the everyday here in Slab City.

García Márquez famously said that “surrealism runs through the streets” of Mexico, and the uncanny is the everyday here in Slab City.

I’m with the district attorney’s office, a man’s voice announces from the doorway.

Can you help me find someone?

From the other side of the library, Cornelius calls out: They’re patrons of the library. Leave them alone.

Sitting on a bench further in, the other patron looks up from her book, and I point to the back as the agent, hired by Missouri’s social services department to investigate a couple and their children, walks in and continues his questions:

Can you tell me where Slab City #99 is?

No, haven’t heard the address before.

Cornelius’ answer is patient but blunt.

Do you know who this person is?

Everybody goes by nicknames here.

If I can’t find them, I’ll have to shut them off from EBT. I just want to make sure they get their money. Two kids are with them, they would be thirteen and sixteen now. … This is an unusual place.

Thanks, we’ve been fixing it up for the past two years or so.

Here’s my card, please let me know if you hear from them.

Cornelius accepts it like a donation to the library. Tires crunch on gravel, and the realities of electronic benefits transfer recede back to El Centro and Missouri. No due dates. No library cards. This is not one of Carnegie’s libraries, but it remains in that spirit of free access. On the front doorway’s jamb, I read Ships are safe at harbor but that’s not what ships are built for, attributed to unknown but coined by John A. Shedd, an author and professor. His name appearing alongside the industrialist’s in a turn-of-the-century Journal of Education, Shedd was a contemporary of Andrew Carnegie, who might have followed with his own platitude: “Think of yourself as on the threshold of unparalleled success. A whole, clear, glorious life lies ahead of you. Achieve! Achieve!” Without any of the capitalist underpinnings, the Lizard Tree Library, as a vessel of books, has dutifully left port to occupy this liminal place in the wake of Carnegie and his Free Libraries: “A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.”

Here, springing from another desert, this oasis of books reminds us where free resides. A library in the open. When it rains, many of the books get wet, but they will quickly dry.

Charlie Hailey, Professor in the School of Architecture at the University of Florida, is the author of, among other books, “Camps: A Guide to 21st Century Space,” “The Porch: Meditations on the Edge of Nature,” (University of Chicago Press), and “Slab City: Dispatches From the Last Free Place,” from which this article was excerpted. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2018.