I Made a Video Game of “The Artist Is Present.” Marina Abramović Couldn’t Sit Through It.

It’s May 15, 2013, and I am sitting directly across from Marina Abramović, arguably the world’s most famous performance artist. She’s wearing a red T-shirt and her hair is in a braid over her right shoulder. The setup is not a little like experiencing her famous performance “The Artist Is Present” except that she’s on my laptop screen via Skype and we’re not being completely silent — we’re talking about time and video games. How did I get here? Let’s rewind a little . . .

Back in 2011, I was teaching an experimental game design course at the IT University of Copenhagen. On the second day of class I spoke about different kinds of experimental art and artists, including Marina Abramović and “The Artist Is Present.” My point at the time was to get the students thinking about the broader idea of bringing an experimental mindset to their work.

In many ways, Abramović’s performance was an extraordinarily simple work: She sat in a chair in the atrium of MoMA in New York City and invited visitors to sit opposite her. While sitting, neither the visitor nor Abramović spoke, they just maintained eye contact. When the visitor felt they were finished, they left, and the next person in line took their place. Abramović performed this work every day the museum was open, for eight hours each day, for almost three months. She sat with her silent guests for 716 hours in total.

By the end of class that day, I found myself proclaiming that I would make “The Artist Is Present” into a video game. At first this was bravado, a gesture to show the students that you could make a game about anything, even “just” sitting in a chair for a very long time. Abramović’s performance is anything but straightforward, though, and my bravado was rewarded with the difficult task of figuring out how to represent it accurately. What I’d thought was a “one-liner” game about doing nothing turned out to be much more than that. As I thought more about the specifics of a potential video game version of the performance, I came to realize that much of the real attraction and interest surrounding the original work is about the audience experience of its long duration.

Over the course of its run, more than 1,000 people sat with Abramović, silently holding her gaze. One person found it so moving they returned 21 times. Some people sat for a few minutes, but more than one sat for hours, matching, to some small extent, Abramović’s feat of endurance. Many, many people were brought to tears by looking into this woman’s eyes. There was a tremendous power and tension in that time of sitting. Logistically, too, the audience experience was heightened. The work rapidly became wildly popular and slots for sitting with Abramović were in demand. Long queues formed outside the museum before opening time and there were mad dashes to get to the front when the doors swung open. People waited in line for hours, tingling with anticipation. To sit opposite a woman in a red dress.

The beauty of waiting and its attendant feeling of expectation is how much it helps us experience time.

I decided that my “The Artist Is Present” would put the player in the role of an audience member and that it would be a game made out of time. I was thinking both about Abramović’s concept of “long durational performance” and its focus on the present moment, but also the audience’s time and how much of it they spent waiting. The beauty of waiting and its attendant feeling of expectation is how much it helps us experience time. I was confident that a game about time — about waiting — was a terrible idea by most metrics available to evaluating “good” game design but that just made me sure it would be a worthwhile project. Something interesting was bound to come up if I started a conversation with time in video game form. Let’s now pay a visit to the virtual Marina Abramović of that video game. Let’s play “The Artist Is Present.”

The game opens outside a pixel-art version of MoMA’s front entrance. The graphics are in the style of Sierra games from the late ’80s. Our character is randomly generated, we’re just another visitor to the museum, not a fantasy warrior or a super-soldier. When we approach the doors, a message pops up:

The Museum of Modern Art is closed. Our hours are: Wednesday—Monday, 10:30AM to 5:30PM. Closed Christmas and Thanksgiving.

It seems we’ve come when the museum is shut. You see, the game keeps the same hours as the real museum in New York City, right down to taking account of the time zone and time set on your computer. This is the first indication that time here may not function in quite the same way we’re used to from other video games we’ve played; it’s a little introductory inconvenience. Oddly enough, though, I’ve only ever had positive feedback from players about this aspect of the game. They have felt real pleasure at the idea of a game being closed, as if respecting real-world time lends more substance to the virtual world. At any rate, we’ll have to wait until a little later . . .

We’re back, having checked the day and time in New York. Now when we approach MoMA’s doors, they slide open. We arrive in the ticketing hall. To enter the guarded exhibition area to the right, we need to buy a ticket. It’s $25, but don’t worry, it’s just play money.

As we go through these motions, we relax into a more familiar sense of video game time: We are the fulcrum of the world, and the game seems to merely wait for us to act. Now time is not so much a continuous thing but rather a punctuation of specific events: buy the ticket, greet the security guard, walk through the door. We appear to drive time forward with our own agency.

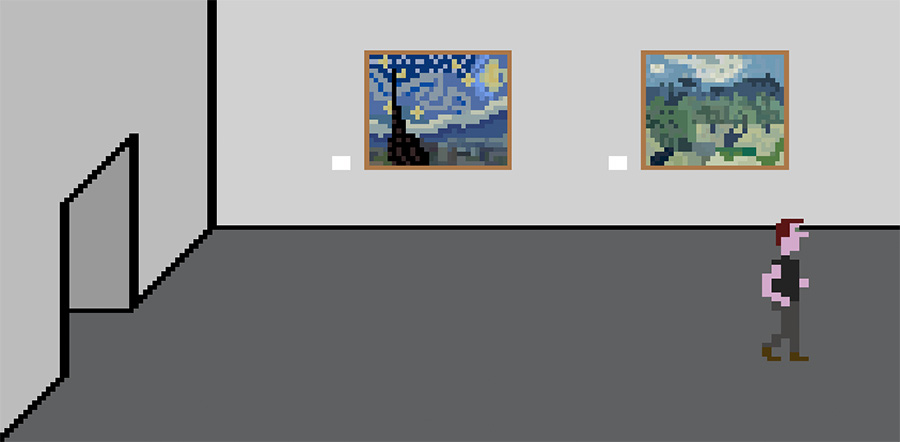

Finding ourselves in a hallway running left to right, we set off past blocky reproductions of famous artworks in the MoMA collection. “The Starry Night” and “Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background” by Van Gogh are in this section. We move forward at 20 pixels-per-second, feeling effective. In video games, this is another fundamental indicator of the passage of time — we’re getting somewhere, it’s time well spent. Again, time is so often measured by our ability to act. Indeed, in many games, when we stop moving, the world itself stops and waits too.

In the next section of the hallway, we see Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans,” but we also see the back end of a queue of people. Here we come across something that is less common in play but that is in fact an iconic image of a real-world relationship to time: waiting, a form of time we’re predisposed to dislike. This is odd, though, for at least a couple of reasons. One is that queues are a bit like rainbows: There’s the anticipation of something valuable at the other end, a treasure like a renewed passport or an excellent brunch. And another, perhaps more poetic, reason is that queues encourage us to experience time, to be present, much in the way of Marina Abramović’s long durational performances. Being in a real-life queue can feel uncomfortably present indeed.

All this is in direct contradiction to many game design principles, from avoiding repetitive and boring tasks to pursuing flow and immersion. But principles aren’t everything. Let’s venture to the head of the queue to see what the fuss is all about. When we walk into the next screen, we realize this is no small thing: The queue extends across the whole space, in front of Matisse’s “Dance.” There must be at least 15 people waiting. When we pass through to the next screen, we finally see the front of the queue. It terminates at a white line of tape on the floor, monitored by two security guards. Behind the tape are two chairs and a table. One chair is occupied by someone like you, another visitor to the museum. The other chair is occupied by a woman in a vivid red dress with a braid of hair over her left shoulder: Marina Abramović. This is what everyone is waiting for, the gold at the end of that rainbow of time.

At last! We can now put together the demand for our time represented by the queue with the reward offered by the game: sitting in a chair. We’re in a video game here, a medium largely premised on entertainment value for money, so it’s reasonable to think carefully about what’s worth our time. Perhaps this is the moment to turn away in exasperation, as I’m sure many did, but then again, perhaps we can’t help asking ourselves: Could it be worthwhile? This is the same question the original performance provokes, one that is partially answered by the daily queues for the experience of sitting opposite Abramović. It must be worth it after all. And so perhaps we think to ourselves, surely, surely the creator of this game wouldn’t ask me to wait for nothing? Let’s find out.

We retrace our pixelly footsteps, past the Matisse and all the way to the back of the queue. Setting ourselves up behind the last person, we receive a message from the game:

You join the queue to see Marina Abramović. Now all you have to do is wait.

Waiting is often thought of as inaction, as doing nothing, but that’s not what it’s really like. Waiting in its pure form is feeling time passing. And boy does it pass slowly in this queue. When I made the game, I did enough research to get a reasonable sense of the rhythm of the queue as reported by the people who took part in the original performance. I learned that the average time spent by a single visitor was roughly 20 minutes but that there was a huge variance. A majority spent less time sitting with Abramović, but a handful spent far, far longer. To emulate this, the game version allocates a random amount of time each computer-generated visitor will sit from a list of possibilities in minutes.

The other virtual visitors in the game might sit with Abramović for two minutes, or they might stay for eight hours. This unpredictability functions as a variable reward schedule for the player as favored by behaviorists, slot machines, and Facebook. There’s an exciting jolt of action as the queue moves forward, followed by a wait for the next stimulus.

Given that we’re going to be here a while, you’ll probably want to occupy yourself in other ways. There’s only so long you can gaze at the 68 x 42 pixels that make up Matisse’s masterpiece or the hairstyles of the people in front of you. When I played through the game, I devoted an afternoon and evening to it. I watched episodes of “The West Wing,” I browsed the internet, I made an omelet. All told I waited for five hours before I made it to the front of the queue, so do keep yourself busy. This is another element of waiting and our experience of it. Unlike Marina Abramović and her laser-like focus, we inevitably feel the urge to fill the many moments with anything except our awareness of their passing. This is a video game that all but forces us to do other things. Thank goodness for cellphones, right? Maybe you could play “Candy Crush Saga” or something.

Here we are, still waiting. The queue has been advancing and we’ve advanced with it each time. In fact, each move forward has been fraught because there is another twist to all this waiting. I implemented the game to enforce the queue’s rules. If you’re not at your keyboard when the queue moves, after 900 frames of animation (30 seconds) you will be pushed aside by the character behind you, and you’ll lose your place. You just didn’t want it enough, apparently. In the same controlling way, if you have the clever idea of repeatedly pressing the right arrow key to move forward to ensure that you’ll never miss your chance, regardless of whether there’s space, I have bad news for you. The game interprets this as rudely “shoving” the person in front of you. Do it repeatedly and you’ll be escorted out by security.

When I endured my five-hour playthrough, I was checking the game screen roughly every 20 seconds, making sure I’d never miss my chance to move up.

I inserted these two small additions to the game to foreground active waiting. There’s no easy way to circumvent the queue or to automate it, you have to be there, like Marina Abramović. The effect is a hypersensitivity to time as represented by the queue. When I endured my five-hour playthrough, I was checking the game screen roughly every 20 seconds, making sure I’d never miss my chance to move up, fretting about accidentally shoving someone and getting kicked out. Trips to the bathroom were an agony of anxiety. “The West Wing” was a blur. I burned my omelet. This is another dimension to time: Make it the center of your attention, tie it to something you care about, and you’ll develop strong feelings about it. You’ll find yourself in a bittersweet vortex of boredom and anxiety. It’s as if you were wildly oscillating your way through Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s famous diagram of “flow,” never hitting the sweet spot, only the apex and the nadir repeatedly. This is not in the design textbooks.

Somehow, some way, we’re here at the very front of the queue. We’re next! Attempt to remain calm as the person ahead of you rises from the chair to leave. Breathe deeply as the security guard gives you brief instructions drawn from reports of the original performance:

“Hi. You’re next.”

“There are just a few simple rules I need to give you.”

“Sit still, don’t move around.”

“Don’t talk to her.”

“Maintain eye contact the entire time you are seated.”

“That’s it. You can go.”

Trying not to forget how your fingers work, you press the keys to navigate yourself to that coveted chair, now empty and waiting for you. I still remember the buzzing panic of this moment in my own playthrough, the sense that something would go wrong at this critical moment. Whether it’s just cognitive dissonance — “There’s no way I would have waited this long for something that’s not worth it” — or whether the experience in the queue is in some weird way transcendent, I can assure you that there is a deep significance here. And others I have spoken to have felt it too. Somehow, despite doing “nothing” for the last several hours, you feel exhausted and elated, ready to take your place in the pantheon of those who have what it takes: time.

When Marina Abramović emailed me back in 2013, she reported that she had played the game herself. Could there be anything better than the thought of this epic performance artist sitting down at her laptop and guiding her character through the hallways of the museum she knows so well to join a queue to sit with . . . herself? It was music to my ears. And so was learning that she’d been pushed out of the queue because she had wandered off to make lunch. Even during our conversation on Skype, she was sautéing onions. It turns out that not everyone’s cut out to wait in a queue to sit with virtual Marina Abramović. Not even Marina Abramović.

Pippin Barr is Associate Professor of Computation Arts at Concordia University. Barr has collaborated with artists including Marina Abramović and @seinfeld2000 and produced games about everything from airplane safety instructions to chess to parenting. He is the author of “The Stuff Games Are Made Of,” from which this article is adapted.