How the FBI Destroyed the Careers of 41 Women in TV and Radio

“How do you tell a Communist? Well, it’s someone who reads Marx and Lenin,” joked Ronald Reagan in 1989. “And how do you tell an anti-Communist? It’s someone who understands Marx and Lenin.”

Reagan, most likely, never read Marx or Lenin, and if he did, he certainly didn’t understand them. However, he understood what he was doing when he invoked the fear of communism to win elections in 1980 and ’84.

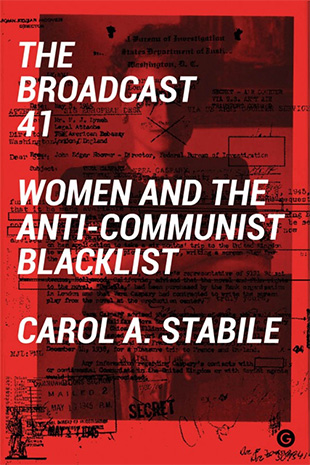

But even before that, beginning in the 1960s, he employed a different tactic to appeal to another fantasy: As Carol Stabile, a professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at the University of Oregon, writes in her book “The Broadcast 41: Women and the Anti-Communist Blacklist,” Reagan “used the phrase family values to attack groups that did not conform to anti-communists’ preferred version of Americanism: welfare moms, people of color, immigrants, students, and his progressive critics.” In fact, adds Stabile, Reagan’s 1980 campaign (“Let’s Make America Great Again”), like Donald Trump’s 2016 revival, drew on sexist, isolationist, and white supremacist visions of the past rooted in the television narratives anti-communists had created in the 1950s.

In the conversation that follows, Stabile and I discuss the beginnings of the FBI’s anti-communist crusade and what might be learned from the stories of the women who were censored and purged from television in the 1950s — a powerful backlash against progressives in media who were seen as a threat to the traditional portrayal of the American family on the airwaves. We also discuss what this history might tell us about current debates on free speech and “cancel culture.”

A stream and lightly edited transcript of the podcast, which was recorded in October 2020, can be found below. You can subscribe to the podcast at Apple, Spotify, or Podbean.

Sam Kelly: How are you feeling about the election?

Carol A. Stabile: I remember the days after the 2016 election and waking up and thinking to myself, “This is really bad. Maybe this is the worst it can get.” But in the years since it’s like we’re just seeing it totally fall apart. I was finishing up the book as Trump was elected and he is the inheritor of the legacies I’m critical of in the book. It was startling to me. In retrospect, that was foolish on my part. It was almost as if the decades between 1950 and 2016 hadn’t even happened. His obvious white supremacist positions, his misogyny, the attacks on immigrants. It was like being in some horrible time machine.

SK: I agree. The book is a great roadmap for American politics today. Can you begin to explain the history you’re writing about in this book?

CAS: My project started percolating in the 1990s; I was struck by the contrast between American politicians’ attachment to the idea of “family values” and the reality of their own families. Whether you looked at the right arm of American capitalism or the (so-called) left arm of American capitalism. From the Bushes to the Clintons, it’s all about “family values.”

I started thinking about where this story came from and the conditions in which those stories were created so that they could be re-invoked by generations of politicians who had grown up with a fantasy of American identity and American families. This led me back to the early days of television. A lot of this discourse invoked televisual representations of family rather than actual families. Reagan couldn’t exactly use his own family as an exemplar to support his political vision. I started looking at who was working in the industry in the years after World War II. What I discovered was very different than what I had been taught. There is a sense that when we look back on the history of media that marginalized groups like women and people of color just suddenly appear on the scene in the 1970s. In fact, these struggles are a central part of the history of those industries.

Imagine American television if W.E.B. Du Bois had been a news commentator at CBS. This was one of the things that the FBI was really concerned about.

I also found that there was a great deal of optimism after World War II, that people could use television to promote civil rights, democracy, to educate and uplift people. Then you have the blacklist. By 1950, many of the innovators who had written and worked on progressive programs prior to 1950 were out of the industry. They had been silenced by the force of the anti-communist backlash. A lot of the book is based on FBI files which I’m still receiving 10 years later. What’s revealed in these documents really emphasized that there was this whole other possible trajectory for TV. Imagine American television if W.E.B. Du Bois had been a news commentator at CBS. This was one of the things that the FBI was really concerned about. And this was a real possibility, CBS was actually talking about the whiteness of their newsroom and the need to have rich and varied voices.

SK: Your book challenges the idea that the white conservative consensus of that era was naturally occurring and in fact, you highlight that it took a huge amount of effort, money, and labor to manufacture that consensus. The stories of the Broadcast 41 are an example of what that manufacturing process looked like. This was a group of women who were working in television who were attacked for their politics. Could you talk about those women?

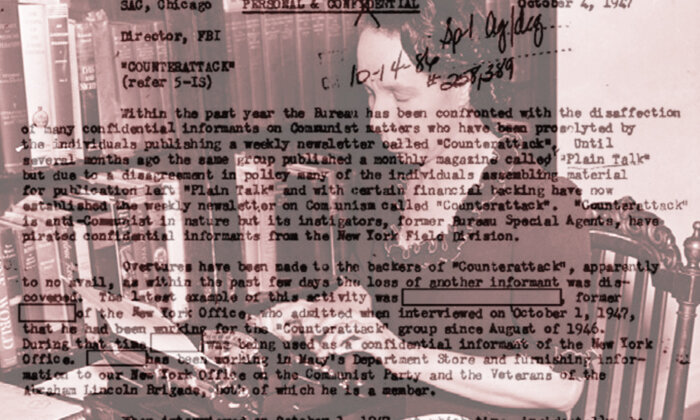

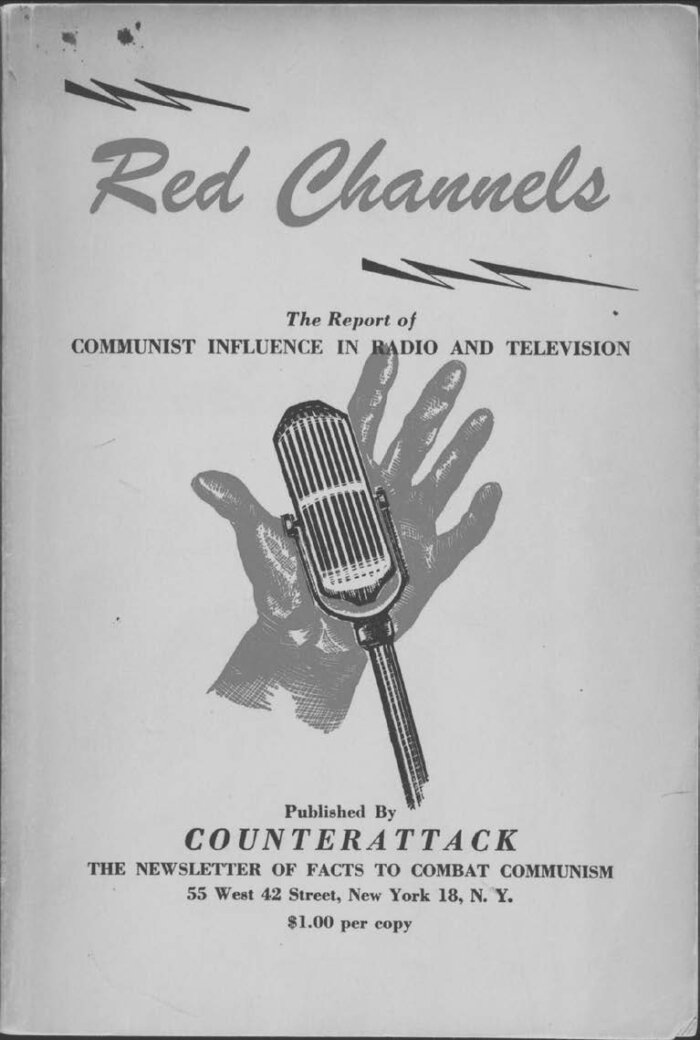

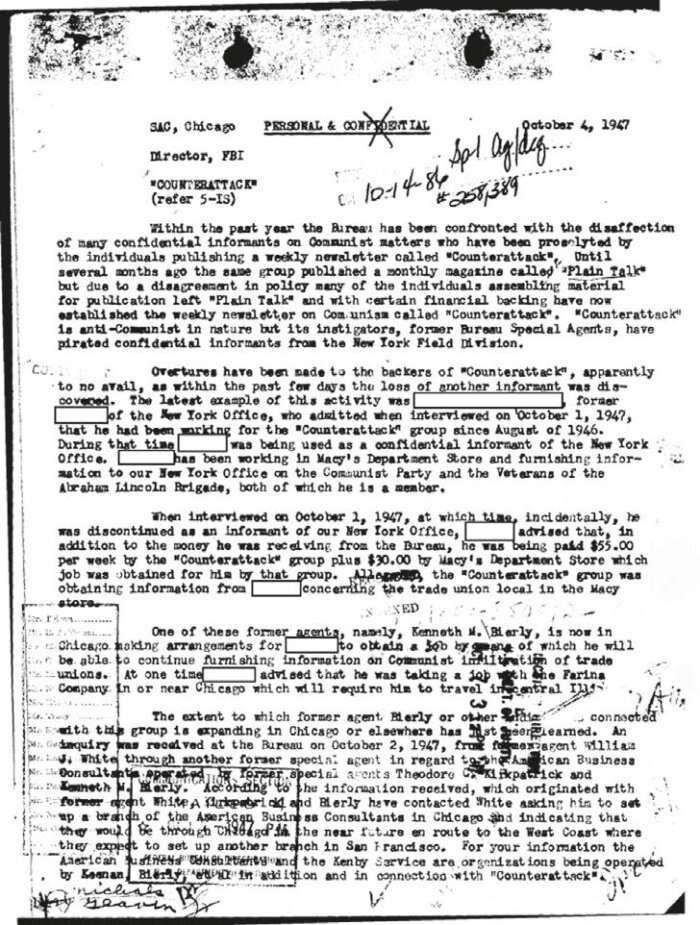

CAS: In the 1940s, the anti-communist movement was using media to suppress dissent and ensuring that alternative viewpoints didn’t get any air time. One of the instruments used to do this was a blacklisting magazine called Counterattack. The founders of Counterattack published what they called “factual information” to distinguish their brand of information from the supposedly propagandistic information purveyed by proponents of civil rights. In 1950 they published a book called “Red Channels” (referred to as the Bible of the Blacklist). “Red Channels” is very influential in the television and broadcast industry. It was used to screen personnel. It was used by networks and agencies to generate their own blacklists. That document became a primary source for me. It’s also worth noting that the American business consultants who published both Counterattack and “Red Channels” were all former FBI agents who maintained deep connections to the FBI.

Reading “Red Channels,” I noticed that in an industry that was overwhelmingly male: 41 of the 151 people listed in the pages were women. That surprised me so I started looking at the profiles of these women, and found that it was a fascinating group. Anti-communists were casting a wide net so some of these women were classical musicians, some of them were choreographers or actors. A handful were writers, like Vera Caspary. Some were members of the Communist Party, such as Shirley Graham Du Bois, whose husband was W.E.B. Du Bois. Vera Caspary was also a member. Some of these women were liberals. Some of them were blacklisted simply for their support of the New Deal and Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the depression. There was a wide range of politics within this group, representing positions from across the spectrum of American left.

SK: Could you talk a bit more about the institutions driving this operation, specifically the FBI?

CAS: The anti-communist movement begins after World War I, born out of the fear that there might be a revolution in the United States, similar to the Bolshevik Revolution. During World War II, the attacks on progressives in the media lessen. There are other things going on. It wasn’t an opportune moment to invoke fears of communism and socialism. But they start to ramp up almost immediately after World War II. There’s a lot of concern about the growing power of the civil rights movement. And even though “communist” is the name they give their targets, a lot of the fears are fueled by white supremacy and the fear of civil rights.

In fairness, in the United States, the Communist Party was the only party to support a federal anti-lynching law. The Communist Party, whatever else you want to say about it, had views on race that were far more progressive than either of the two official parties. Meanwhile, the FBI has been gathering information on so-called communists for as long as it’s been in operation. It’s been propagandizing against communism and socialism since the mid-1930s when the FBI establishes The Crime Records Bureau, which is their name for its public relations operation. These forces converge with veterans’ organizations, which some historians have pointed out are — this may a metaphor I take back — akin to super spreader events for white supremacy.

They’re breaking into buildings illegally; they’re conducting illegal wiretaps. The FBI is very hands-off because their political beliefs align and they’re happy for it to happen.

The FBI is also ramping up its surveillance of domestic dissidents and they have a whole range of operations called comm-fil programs (communist infiltration.) These are precursors to the better-known counter-intelligence programs of the ‘60s and ‘70s that are aimed at organizations like The Black Panther Party and The American Indian Movement.

The anti-communist movement is really focused on three things: civil rights, trade unions, and media. The movement itself is made up of the FBI, but also people leaving the FBI who want to make some money in this newly emerging security/surveillance state. They’re especially concerned with New York City, which is seen as a hotbed of communist activity. That’s the crucible out of which the American Business Consultants emerges. Even though this organization has a short run (from roughly 1947 to 1952) their impact is disproportionate to their size. They’re breaking into buildings illegally; they’re conducting illegal wiretaps. The FBI is very hands-off because their political beliefs align and they’re happy for it to happen.

SK: How did these groups affect the careers of these women?

CAS: This morning I was thinking about what Marshall McLuhan said, and sometimes the message is the message. Anti-communists were very effective in using strategies and tactics we’ve seen over the last four years. They smeared people without evidence. And like on Twitter, you can disprove something, but once you put it out there, it’s out there.

You didn’t even have to belong to the Communist Party. They had this term “fellow traveler” that encompasses anyone who wasn’t willing to publicly support anti-communist principles in politics. They smeared people and called them in front of The House Un-American Activities Committee. They promoted rumors and gossip, all of it without factual backing. There were some cases where people did fight back and made them correct their errors in the pages of Counterattack. But as someone once said of Jean Muir, the first actress to be targeted, it’s like a bruised Apple. Once the Apple is bruised, the taint remains. And even if you defended yourself, it just feeds the publicity.

SK: What kind of surveillance was taking place?

CAS: In some cases, people were followed by the FBI. Madeline Lee Gilford, for example, who had two small children, she got to know the FBI agents who were parked outside of her house on a daily basis. The FBI was tampering with people’s mail, getting information about bank accounts and looking at their financial records. In a number of cases, people could no longer get passports. Which was terrible for musicians in particular, who could still work in Europe, but because they were denied a passport could no longer travel and make a living. Agents cultivated confidential informants from their friends and their workplaces so that it became a very paranoid period, you just didn’t know who among your circle of friends and coworkers might be providing information to the FBI.

SK: What effect did this program of sustained intimidation have on the American media landscape?

CAS: It removed a lot of very, very talented people from the industry. People who had progressive points of view. People who were involved with films like “Gentleman’s Agreement” (1947) which is about antisemitism in the United States, and used a lot of blacklisted talent. There’s also “Counterattack” (1945), which was written and produced by Adrian Scott, one of The Hollywood 10.

People learned to self-censor. People who remained in the industry realized that there were topics that had become associated with communism that you couldn’t talk about. Immigration is one. Before the 1950s, there are a good number of what were called “ethnic sitcoms.” These sitcoms, which it’s worth adding still trafficked in terrible stereotypes, became untouchable in the 1950s.

People learned to self-censor. People who remained in the industry realized that there were topics that had become associated with communism that you couldn’t talk about.

If you look at the history of immigrants on American television, you can see that no one wanted to take on a topic that (no matter how you deal with it) is going to be seen as controversial. That is a chilling result of anti-communism, which became part of the structure of the industry. People just learned. We all know. We work in various places. There are some fights you think you could win and some you can’t. Writing about race, writing about women’s liberation, writing about immigration, all became very controversial. While there were people who still manage to do some of this work, it was not easy to do it and it certainly wasn’t encouraged. Can I give you just one example that I love?

SK: Please do.

CAS: Okay. Do you know the BBC program “The Hour” (2011), which was about a BBC newsroom in the 1950s?

SK: Yeah.

CAS: If you look at that alongside “Mad Men,” I think you get a sense of the long-term effects. In “Mad Men,” what you have is a fantasy of the 1950s in which women aren’t part of the industry at all. They just accidentally happened into it. They’re kind of stupid, and get pregnant without even knowing it, until they give birth. But if you look at “The Hour,” it’s a really different depiction of the struggle faced by women in that industry. There were women in the industry. I think that you get a lot of historical representations that are warped by the anti-communist lens.

SK: I’m really glad you used the word fantasy there, because one of the fantasies prevalent at the beginning of the book is the image of the “post-war American family.” It’s an image of a white heterosexual, gender normative, patriarchal family, that is, as you write, drawn on over and over again by the likes of Reagan and Trump. Their deployment of “family values” is never the values of access to education, access to healthcare, access to childcare. Can you talk about hierarchies being reaffirmed in those kinds of anti-communist “family values”?

CAS: Yeah. Make America great again, huh? I mean, MAGA is based on a fantasy of what the country looked like: a self-reliant, economically solvent, white unit that has always been out of sync with the reality of many Americans. But it’s very useful as a trope. Reagan invokes it later in life. And let’s not forget Reagan’s role as an FBI informant and a union buster who worked to suppress progressive views in Hollywood. These were people who knew what they were doing, who knew that they were appealing to was a white fantasy about America.

American television has only recently included representations of black families that aren’t pathologized.

Even before the 1950s, the anti-communists were very deliberate in creating a particular vision, then protecting and defending it. I think what happens with television in the 1950s is that they have the opportunity to create an industrial product that is then reanimated for decades and decades. American television has only recently included representations of black families that aren’t pathologized. And representations of immigrant families and their struggles that aren’t “The Godfather” or something.

SK: All of this is also dependent on set roles for men and women. Can you talk about the decision to write specifically about women that were blacklisted and their experiences of facing fights on multiple fronts? By that I mean, not only struggling for civil rights and workers’ rights but also facing homophobia and misogyny in those struggles themselves.

CAS: Looking at those 41 women who were blacklisted, many of them were the children of immigrants. Many of them did not conform to norms of gender or to sexuality. And as you put it, they were struggling on multiple fronts. Think about Margaret Webster, who was a lesbian working in theater, whose work was really focused on addressing segregation. Her commitments were to civil rights and the rights of refugees and immigrants.

Maybe this is my optimism but I love stories about people who did the right thing at a moment in time when it was so hard to do the right thing. When the price you paid for doing the right thing could be so steep. I think about John Brown, and I think about these women who knew the forces that were gathering against them and stood by what they thought was politically right and true. For example, there’s this whole group of (what we would now describe as) queer women in and around women’s publishing and broadcasting that no one’s written about. Their politics are very intersectional. There were also women whose lives didn’t conform to a gender binary.

Maybe this is my optimism but I love stories about people who did the right thing at a moment in time when it was so hard to do the right thing.

There’s Dorothy Parker and Lillian Hellman who have been framed as through this lens of difficult women. Because of course, men in the industry weren’t difficult. And someone like Shirley Graham Du Bois, who broke so much new ground. But because of anti-communism, her books are out of print. She’s only now starting to receive the attention that other authors have because their reputations weren’t ruined in the same way.

SK: It makes me optimistic, but also in another way, it makes me quite depressed, to think of how many of the exact same anti-communist narratives are still prevalent. For example, the idea that women not serving their role as subservient housewives, who are sexually and financially independent is somehow the root cause of the decline of Western civilization. In one sense that is completely absurd, but it’s a story that’s deployed by very popular figures on the right from the likes of Prager U, Jordan Peterson, Ben Shapiro, etc. Another recycled narrative is that black and indigenous people aren’t organizing their own actions. That instead, there’s actually a secret conspiracy orchestrated by communists. Could you talk about why those narratives are still so prevalent, how they function and how we might reframe them?

CAS: That’s such an important question. I was thinking about this with reference to Trump’s increasing emphasis “law and order” because clearly, he doesn’t care about law and order when it comes to his own behavior. There’s a story that there has to be some kind of outside agitation and marginalized, oppressed, disenfranchised people cannot make these arguments and organize these movements on their own. What’s so interesting about the last eight months in particular, is that it feels like Trump is desperate and he’s going deep into that historical playbook in ways that make very little sense. For example, his recent tweets about the radical left and Nancy Pelosi. I can tell you; I do consider myself radical and I consider myself a leftist, and people like Pelosi have nothing to do with my politics.

The other thing that’s interesting, too, are the recent attacks on education, which I didn’t talk about enough in my book. The blacklist really effected progressive educators. When I was a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, the provost still had to swear an oath every year saying that no faculty members were members of the Communist Party. And I don’t think that’s changed, honestly. The recent attack on critical race theory and racial sensitivity training is from the same playbook. It shows you the level of fear there is about education and educated people.

SK: I want draw these histories into dialogue with phenomena like the “cancel culture” and “free speech.” Many people are energized by a fear that they’re being censored and that certain ideas aren’t being listened to. This story has so much to say on the question of, historically, who has actually been censored? Which ideas have been deemed unacceptable for serious consideration? Could reflect on those debates with The Broadcast 41 in mind?

CAS: These are authoritarian movements, that like nothing less than being challenged or being questioned. I’m an educator. I spend a lot of time answering questions and talking to my students about things that they don’t understand or places where they disagree. That is an important and valuable is part of the process of education. But again, anti-communists, and in the most recent iteration of Trump, just want to be right. They don’t want to be challenged.

It strikes me as ironic that they have a critique of cancel culture, when they are the ones who refuse to listen to scientists, who refuse to engage in any kind of principled discussion based on research, facts, and things we know about the world. I also think that they hide behind a demonization of social media. This is what I said earlier, sometimes the message is the message. I think people feel that “Well, Twitter and social media, have created such terrible, acrimonious cultures.” But in the research, I’ve done, these women received death threats. They received hideous forms of communication from anti-communists, political organizations and individuals.

Social media has pulled back the veil on some really terrible bullying practices. But I also think it has allowed people, for good and ill, to know that they’re not alone. One of the most terrible effects of the 1950’s blacklist was that it isolated its targets. You didn’t know who you could talk to. You couldn’t find other people who’d had similar experiences. The gatekeepers of traditional media were so fully in charge that it made it difficult to tell alternative stories.

To refer back to notions of free speech, the people who are talking about free speech, they don’t want to have a conversation. They want to have a monologue. And they’re just really angry that principled people are challenging them on their half-baked opinions.

SK: A good example of this happened in the U.K. a couple of weeks ago. The government circulated a document guiding school curriculum. And in the same document, it was stated that teachers must educate children on the risks of cancel culture and censorship, but then a few pages later it stated that teachers can’t educate children using anti-capitalist material.

Nonetheless, lets finish on an optimistic note. I’m asking people to finish off these conversations by advising listeners how they can organize in the lead up to this election. In this instance, Donald Trump and Joe Biden, draw on the anti-communist playbook. What lessons could we take from the struggles of these women?

CAS: Well, despite the shared anti-communist rhetoric, and you’re right to do that because Joe Biden has taken pains to distance himself from those traditions. I do think that there’s a generation, who are interested in these ideas. They’re interested in thinking about history in ways that haven’t been available to them in the past.

That movement, coupled with the movement for racial justice in this country, I don’t think that can be stopped. We have tools at our disposal that previous generations didn’t.

The pandemic and subsequent economic recession is impacting people’s everyday experience. I think that there’s going to be a place for ideas about healthcare, about sharing, about compassion, about a government that cares for people rather than incarcerating and murdering them. I think all of those things are in the air in ways that I haven’t seen in my lifetime.

Another thing I’m hopeful about is reinventing public education in the U.K. and the United States because it’s been so deracinated by neo-liberalism. One of the ways that you get people to agree to authoritarian regimes is by scaring them and preventing them from acquiring the tools they need to be critical.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m terrified. In the next year or so, whatever happens with the election, it’s going to be impossibly hard.

SK: Carol, thanks so much for speaking to me today.

CAS: Thank you, too. Thanks for reading my book and for talking to me about it. I’m glad that there was some part of it that made you feel a little bit more optimistic.

Sam Kelly is the host of the MIT Press podcast and a member of the Press’s publicity and marketing team.

Carol A. Stabile is Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Associate Dean for Strategic Initiatives for the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Oregon. She is the author of several books, most recently “The Broadcast 41: Women and the Anti-Communist Blacklist.”