How the Copy Machine Gave Rise to New York’s Downtown Arts Scene

In the early 1970s, as New York City was in an economic and social downturn, a vibrant arts scene emerged in downtown Manhattan south of 14th Street. From its onset, it was fully aware of its status as a bona fide scene. Over the next two and a half decades, the scene gave rise to a generation of innovative artists, writers, and musicians. Yet, even though the downtown scene generated its share of art world celebrities, it was always defined by a distinctly DIY aesthetic and ethic. As Brandon Stosuy emphasizes in “Up Is Up, But So Is Down,” a compendium of texts and images documenting downtown’s literary scene, writers and other cultural producers here “took an active role in the production process, starting magazines, small and occasional presses, galleries, activist organizations, theaters and clubs,” and this was as true for the scene’s celebrity artists as it was for its cultural producers working in relative obscurity.

Like most scenes, this one was the result of a convergence of historic, economic, and technological factors. As emerging artists actively sought out spaces to occupy rather than negotiate entry to, cheap rent emerged as a key factor in the scene’s development (and at the time, cheap rent was not difficult to find). But cheap rent was not the only factor driving the downtown arts scene; it was also contingent on the growing availability of a new medium: the copy machine.

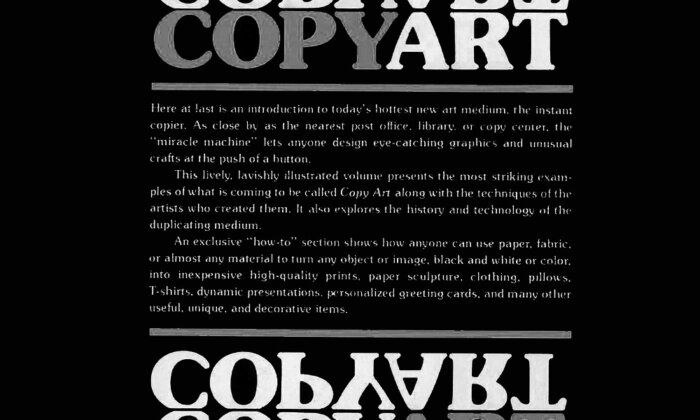

Emerging in the early 1970s just as copy machines started to move out of offices and libraries and into bodegas and copy shops, New York’s downtown scene benefited from this new form of inexpensive print production from the outset: Musicians without agents lined up at copy machines to turn out homemade posters advertising upcoming gigs; downtown artists embraced copy machines as a way to move their art out of the gallery and museum and into the street; and writers seized copy machines as a way to self-publish zines, broadsides, and even books. As Marvin Taylor, director of the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University, observes in “The Downtown Book,” “Downtown work exploded traditional art forms, exposing them as nothing more than cultural constructs. Verbo-visual work, installation art, performance art, appropriation art, graffiti painting, Xerox art, zines, small magazines, self-publishing, outsider galleries, mail art, and a host of other transgressions abounded.” Significantly, most of the art forms listed by Taylor depended on xerography either directly or indirectly: It was either the medium these artists were working with or in, the means by which they were publicizing their work, or the medium of production and dissemination.

Xerography’s platform, in a sense, was the city itself, and anyone strolling by was a potential subscriber.

Not surprisingly, the Downtown Collection, which Taylor founded at Fales in the early 1990s and continues to develop, is a veritable storehouse of xeroxed ephemera. Among the dozens of collections — some donated by individual artist and many others by artist collectives and other downtown organizations and galleries — are countless examples of artworks, posters, flyers, and printed materials turned out on copy machines. Yet, in my various trips to Fales to carry out research, I found it difficult to find a definitive example or set of examples that might help me illustrate just how important xerography was to the development of the downtown scene in the 1970s and 1980s. The collections that comprise the Downtown Collection contain examples of all the types of art mentioned by Taylor — xerox art, zines, small magazines, and mail art alongside thousands of photocopied flyers, ticket stubs, and posters. In some collections, receipts and check stubs reveal just how much money some of the individuals and collectives represented in the collection were spending on xerography at the time. More or less absent, however, are any self-conscious references to xerography. One is left with the impression that, like talking or breathing, xerography was just something people were doing all the time, out of necessity and convenience. For this reason, it wasn’t something anyone spent much time thinking or writing about or documenting in any formal manner.

Photographs of artists hanging out around Xerox machines at all-night copy shops in the East Village may be elusive (which is not to say that such photographs are not in the collection, only that I never found them), but there is no way to visit the Downtown Collection and not leave with a strong impression that in the 1970s to 1980s, xerography was central to the production and dissemination of art and community building in the downtown scene. In some cases, it was how emerging artists established international reputations while conveniently bypassing gatekeepers at established galleries and art museums.

Downtown artists like Jenny Holzer and Keith Haring, for example, experimented with xerography in the late 1970s and 1980s before settling on other media. With few exceptions, however, works turned out on copy machines were rarely labeled or categorized as such. The medium, in most cases, was so taken for granted that it was not always identified as a distinct form of image reproduction, even when being used to produce artworks.

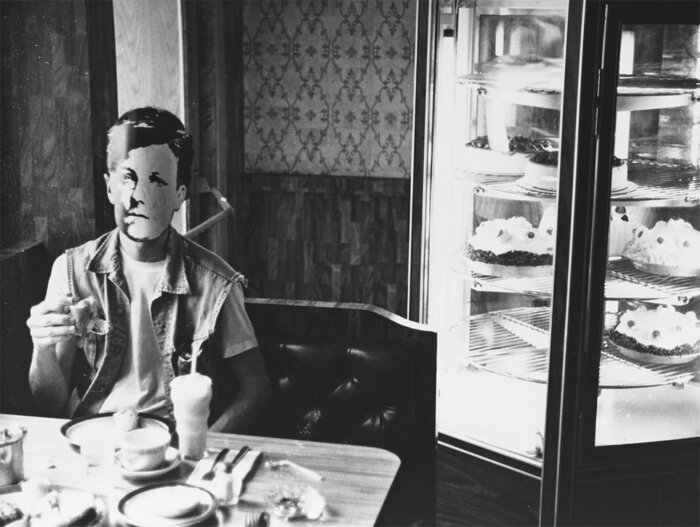

This is precisely why, on one of my trips to Fales, I asked to look at one of the most iconic works to come out of New York’s downtown art scene in the 1980s. David Wojnarowicz’s “Arthur Rimbaud in New York” features a photocopied (yes, I confirmed) cutout of Rimbaud’s face cast against various iconic locations around New York City. In its acid-free folder at Fales, the mask (likely just one of the many versions used by Wojnarowicz in the series) looks like nothing more or less than a hastily produced, photocopied paper mask. In the series, the flimsy paper mask is repeated again and again, and in each photograph the mask is attached to another body in another space — a gesture that not only underscores the ephemerality and mobility of the xerographic medium but also the power of the multiple as a means to quite literally occupy the city.

While Wojnarowicz along with Holzer and Haring eventually received attention in New York and well beyond, for most artists in the downtown scene the copy machine was less a medium of art than a means of communication and publicity. After all, prior to the development of digital social media platforms in the late 1990s, xeroxed posters and flyers were the primary means by which artists and performers took publicity into their own hands. Unlike more recent forms of social media, which are typically only or primarily visible to people who are already members or subscribers, xerography’s platform, in a sense, was the city itself, and anyone strolling by was a potential subscriber.

It’s precisely this democratizing effect that David A. Ensminger celebrates in “Visual Vitriol.” While recognizing that most copy machines were produced by the very sorts of large corporations that no self-respecting punk would ever dream of endorsing, Ensminger concludes, “Xerox and others produced machines that freed punk graphic artists from the demands of money, time, and energy by handing them a machine that could act as a Trojan horse.” The Trojan horse in question enabled punk and its signature aesthetic to carve out visible spaces not only in New York but in cities across North America and well beyond, at a time when many downtowns were more synonymous with abandonment and crime than cultural production. While not everyone viewed punk as distinct from the social problems plaguing inner cities in the 1970s and 1980s (in many respects, punk was where it was precisely because high crime rates and the divestment of properties had left a convenient space for it to fill), at least in New York the punk scene was, from the outset, deeply entangled with the city’s downtown art scene. Punk’s visible presence there in the 1970s and 1980s — the walls of posters and flyers for upcoming shows and events of all kinds that appeared as a result — was a sign of life, of a constantly shifting life force in New York’s downtown landscape. This aesthetic and energy were in turn recirculated in much of the work produced by artists who were part of downtown scene at the time.

Punk’s visible presence was a sign of life, of a constantly shifting life force in New York’s downtown landscape

Xerography, in this sense, offered more than a means of production and distribution that bypassed the expectations and censorship of promoters, curators, and publishers. In the 1970s and 1980s, walls of xeroxed posters and street art distinguished downtown scenes from other neighborhoods by creating constantly changing and highly textured facades. Xerography also effectively blurred the boundary between art making, its context, and its publicity. As a result, as artists, musicians, poets, and performers of all kinds publicized their work and events, the city in turn was transformed. These posters changed what certain neighborhoods looked like and changed the function of these neighborhoods along the way.

In an interview for the ACT UP Oral History Project, Avram Finkelstein, artist and cofounder of Gran Fury, recalls, “Eighth Street was literally papered with posters, manifestos and posters and diatribes. It was literally like a billboard, the entire corridor between the East and West Village, and I remember that as a very vital way that people communicated in the street. It was free. Everyone did it. I remember it as a part of my adolescence.” Artist and activist Carrie Yamaoka, reflecting on the downtown scene in the same period, remembers that “back then, you could look at a wall and see a poster and you knew that so and so is playing at the Pyramid on Saturday. … That is really the way you would find out that something was going on. It was a bulletin board, but the bulletin board was everywhere.”

One might argue that there have always been posters in downtown cores of cities, making what happened as a result of xerography merely an extension of previous forms of urban advertising. This analogy quickly breaks down, however, since with xerography there was a drastic shift in who was producing the posters and how posters were being produced. As Ensminger emphasizes, the postering and flyering that were synonymous with the punk scene and more broadly with artistic production during the punk era were not simply about advertising events. Sometimes, after a show was announced, three or four different posters would appear advertising the gig — some made by members of the band and others by fans (something that xerography made possible by drastically reducing both the cost and time of production). Copy machines not only helped to forge social bonds but also arguably changed who could be an active participant in the making of culture.

After all, as long as the city was a bulletin board and the bulletin board was everywhere, in a sense we were all living in our communication platform. We walked through it, were influenced by its aesthetic, and of course, as my own archival research for this chapter reminded me, we took it mostly for granted too — that is, until downtowns regained their status as sites of economic interest and the aesthetics and content of xeroxed posters began to come under attack.

As downtowns regained their mainstream appeal in the late 1980s and 1990s (both as sites of commerce and as preferred places to live), public postering — with its strong links to art, activism, and the punk scene — was targeted as one of the things to be contained or eliminated (along with other forms of street art). If borrowed time on copy machines and borrowed space on city walls once offered artists and activists a way to carve out a space for themselves in downtowns and actively participate in defining cities, by the late 1990s these practices were increasingly being constructed as antithetical to efforts to clean up, gentrify, and privatize the same public spaces.

Kate Eichhorn is Chair and Associate Professor of Culture and Media at the New School. She is the author of several books, including “The End of Forgetting” and “Adjusted Margin,” from which this article is excerpted.