How Pac-Man Revolutionized Gaming

When Pac-Man arrived in 1980, it didn’t just become a popular video game. It transcended video games. There was Pac-Man cereal in grocery stores, a Pac-Man cartoon on television, and even a hit Pac-Man song on the radio. In other words, Pac-Man blew onto the scene with a scale of cultural impact that video games, already an international phenomenon, had never previously achieved.

In the decades since its release, the game inspired a Martin Amis novel and a fashion collection, not to mention a slew of merchandise, from novelty boxer shorts to a commemorative alcohol from Matsunami Sake Brewery. Clearly, Pac-Man’s appeal goes beyond games.

And yet the games themselves — there have been over 200 releases to date — continue to find a receptive audience. This week, 40 years after Pac-Man’s launch, Google’s Stadia service will release Pac-Man Mega Tunnel Battle, yet another addition to the franchise. And Google is far from alone. In October, Pac-Man creators Bandai Namco released Pac-Man Geo, an app that turns real city streets into Pac-Man mazes; earlier this month, British developers Steamforged Games released Pac-Man: The Card Game, a family tabletop game. So what explains the enduring appeal of Pac-Man?

Just like film has a set of fundamental techniques — angles, cuts, pans, and zooms — there are fundamental techniques of video games. But unlike film’s metalanguage, which we’ve been discussing for a century, we are just starting to understand the fundamentals of video games — how their operations create meaning and shape our playing experiences. This is where Pac-Man blazed new trails.

Unlike film’s metalanguage, which we’ve been discussing for a century, we are just starting to understand the fundamental techniques of video games.

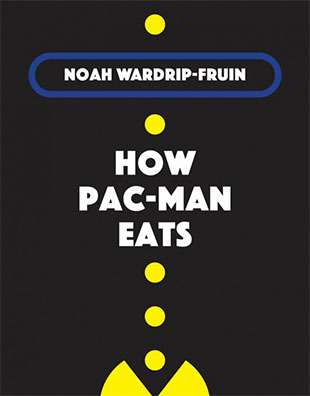

In my new book, “How Pac-Man Eats,” I explain the design innovation that made Pac-Man possible — and so impactful — and explore how game developers still apply that approach to the fundamental techniques of games today, broadening the ideas that they can express.

One of these techniques, collision, is the fundamental action of one game object running into another. It’s so familiar to every video game player that most probably don’t give it a second thought, but it’s worth unpacking the significance of this operational logic. Collision was a core element of the games that dominated arcades and home consoles before Pac-Man’s arrival, such as Asteroids and Space Invaders.

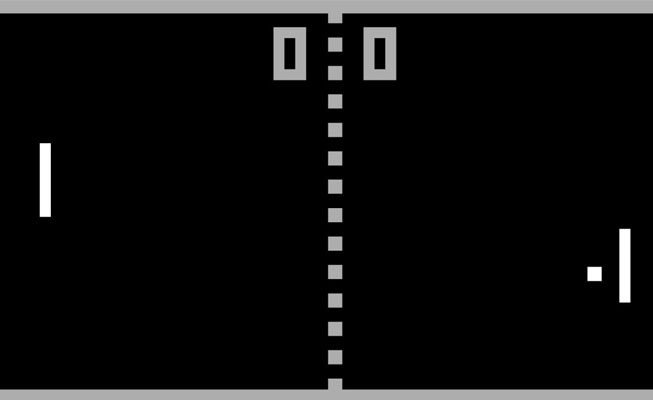

These games were hugely successful, inspiring the opening of arcades across the U.S. and around the world. Space Invaders even took over the cultural position of Pong, becoming the common cultural reference for a video game — such that its descending aliens are still used as an icon for video games even among people far too young to have played it in the late 1970s.

But Pac-Man took things to a new level. People wanted to watch a Pac-Man cartoon because Pac-Man felt like a character. This was something no previous game had really achieved. And the key to this wasn’t technological. Pac-Man’s simple animated circle was no technical leap beyond the player’s ship in Space Invaders. Rather, Pac-Man felt like a character because of the game’s new approach to collision.

Collision in many of the earliest video games — Asteroids and Space Invaders, for example — was entirely literal. It meant “one thing bumping into another,” with resulting effects. Spacewar!, developed at MIT in the early 1960s, featured two space ships that could (fatally) collide both with a star at the center of the screen and with missiles fired by the other player. Pong, the first video game to achieve public success, featured two paddles that each tried to collide with a ball they rallied back and forth, with players scoring points when the ball hit the other player’s side of the screen.

In Pac-Man, collision instead expresses something metaphorical. The physical act of collision stands in for the physical act of consumption — of eating. It was this, rather than more detailed graphics or more fluid controls, that made Pac-Man feel like a character that players could identify with. This is something the people behind the game understood. As Dennis Lee, the director of brand marketing at the U.S. division Bandai Namco Entertainment, the company that created Pac-Man, told the radio show Marketplace: “Eating is just a very universal, humanistic characteristic.”

“Eating is just a very universal, humanistic characteristic.”

This shift wasn’t something that the company stumbled into by accident. Rather, the creative team was explicitly looking for a way to make a game about something new that would explore new experiences and appeal to new audiences. In the Netflix documentary series “High Score,” Toru Iwatani, who led the team that developed Pac-Man, recalls wanting to make a game that moved beyond Space Invaders-style death: “Eating doesn’t involve killing each other,” he muses, “and maybe women can enjoy it as a game too.”

In “How Pac-Man Eats,” I call this kind of approach to the fundamental elements of games expansive. It’s an approach that new generations of creators continue to rediscover and use to open new possibilities for what games can be about. I describe, for example, how an expansive approach to collision is at the heart of Dys4ia, trans designer Anna Anthropy’s autobiographical game about beginning to take estrogen. Now that game players are accustomed to expansive uses of collision, designers like Anthropy can dial up the level of metaphor considerably — using collision to express everything from the power dynamics of a conversation to a personal experience of body image.

The Google Stadia executives who decided to make a bet on Pac-Man Mega Tunnel Battle are unlikely to have any idea that the original Pac-Man is at the root of a rich design tradition. But they certainly know of Pac-Man’s deep and lasting cultural impact. As we learn more about the fundamental elements of games, and come to understand the games that use them in new ways, the door opens for more creators to deliberately use games to change our culture.

Noah Wardrip-Fruin is Professor of Computational Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where he co-directs the Expressive Intelligence Studio. He is the author and editor of several books, most recently “How Pac-Man Eats.“