How James Garfield’s Assassination Gave Birth to the American News Cycle

Only a few minutes separated President James A. Garfield from the beginning of his summer break from the business of the White House. Starting from the Baltimore & Potomac Railroad Station on the morning of Saturday, July 2, 1881, he planned to retreat to his farm in Mentor, Ohio. But first, the president needed to attend his 25th-year reunion at Williams College, where he’d give a speech and receive an honorary degree. Garfield was also delighted because soon he’d see his wife, Lucretia, who had been recovering by the ocean in New Jersey from malaria. In just a few short hours, the train would transport him to her, and they’d be together feeling the breezes by the Jersey shore.

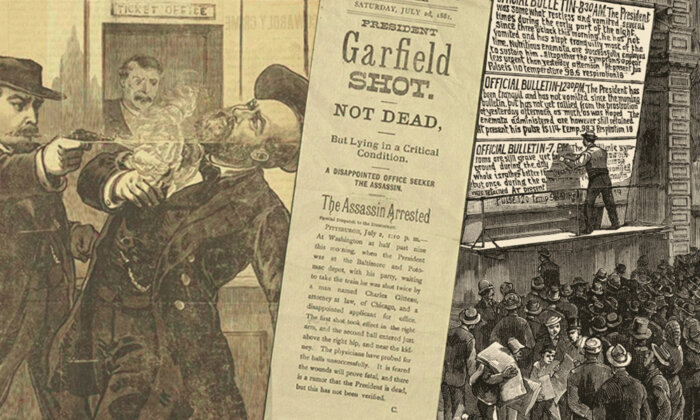

For Garfield, this day was long overdue, and he couldn’t escape soon enough. The sweltering temperatures of the nation’s capital steamed him like a crab from the nearby Chesapeake Bay. When Garfield sprang out of the carriage in front of the train station, he bounded his burly body up the stone steps of the B Street entrance and glided past the rows of wooden benches in the small and serene front space of the ladies’ waiting room. As he headed toward the main hall, he heard a firecracker pop and then felt the searing rip in the skin of his right arm. Then, a second pop rang out, and an avalanche of pain in his back seized him, causing his body to thud, knees first, to the marble floor.

James G. Blaine, the secretary of state, had accompanied the president to the train station to squeeze in a few more minutes of business during their carriage ride. These men, both bearded and charismatic, walked into the station arm in arm, lost in a conversation about how they would enter the new Garfield presidency into the history books. But as Blaine witnessed his friend topple to the floor, the euphoric bubble of their conversation burst, and this seasoned politician and orator cried out, “My God, he has been murdered.” There were many great and important things to accomplish on Garfield’s return from his vacation. But all those dreams and ideas fell to the floor, along with Garfield’s body.

The next few minutes were the longest. As Garfield looked up, hovering over him were unfamiliar but learned faces. Nearly a dozen doctors came to the president’s side, summoned from the station, from the street, and from nearby practices. An unbearable pain consumed him, making his mind at once cloudy and clear. One by one, doctors turned Garfield over to inspect his injury, and each time, a pain rushed over his body, as uncleaned fingers and surgical probes entered his wound. When the misery inflicted by these physicians was over, the doctors did their best to reassure him, although uncertain themselves, that he would survive.

Garfield, positioned on the precipice between the living and the dead, had one mission, too: to see the dawn.

Eventually, Garfield was moved to the White House in a horse-drawn ambulance. Each brick of the road jostled the carriage, pulsating his pain, while his life seemed to drain out along with the blood staining his summer gray suit. At first, doctors convinced themselves that Garfield would live, but with a closer examination and more time, they reconsidered their medical opinion.

In addition to the unending pain he was experiencing, Garfield had one thing on his mind: his wife. He asked his close army friend, Colonel Almon Rockwell, to send a message to her in Elberon, New Jersey. When Lucretia opened an unexpected telegram that same day, it said, “The President wishes me to say to you that he has been seriously hurt.” The note ended with, “He is himself and hopes you will come to him soon. He sends his love to you.” The frail Lucretia, located a few hours away from her husband in New Jersey, had one mission: to get to him quickly. Garfield, positioned on the precipice between the living and the dead, had one mission, too: to see the dawn.

James Abram Garfield was noted by all who knew him to be a kind, honest man, of strong will and intellect. He grew up poor on an Ohio farm outside of Cleveland, and studied his way out of poverty. His brilliance was beyond measure, but easy to display. Legend has it that he could translate an English passage into Greek with his one hand and into Latin with the other — at the same time. Garfield became the president of a small college, was a general in the Union Army, and was a House representative for the state of Ohio before he took on the highest position in the land as the nation’s 20th president. At age 49, Garfield, with his stout chest and bright blue eyes, was destined to be one of the country’s greatest presidents. Like Lincoln, he was forward-thinking about Black people, and, like Kennedy, he was a charming orator with a celebrity presence. But also like these men, Garfield found himself on the devastating end of an assassin’s gun.

Charles J. Guiteau, a 39-year-old drifter, shot the president. Slim and slight at 130 pounds, Guiteau wore a dark suit on that summer day and had a brown beard, a jaundiced complexion, and disengaged gray eyes. Guiteau, who by all accounts was unstable, was a prolific underachiever: He failed at law, at selling insurance, at evangelism, and later at starting a newspaper. He had no Midas touch, but there was no convincing him otherwise.

At the train station, Guiteau had a letter in his pocket admitting that he shot the president as a “political necessity,” so that another faction of the Republican Party, which Guiteau fanatically supported, could be in charge. Originally from Freeport, Illinois, he bounced around from upstate New York to Chicago to Boston to Hoboken, New Jersey, often skipping out on paying his rent at each hop. Guiteau had hopes of getting an office position in one of the thousands of openings within Garfield’s new administration. He was seen at the White House on over a dozen occasions, having his eyes set on being a consul general to Paris. While he was dismissed every time, he never got the hint why. Somewhere along the way, Guiteau got the inspiration to remove Garfield. He once wrote, “If the President was out of the way, everything would go better.”

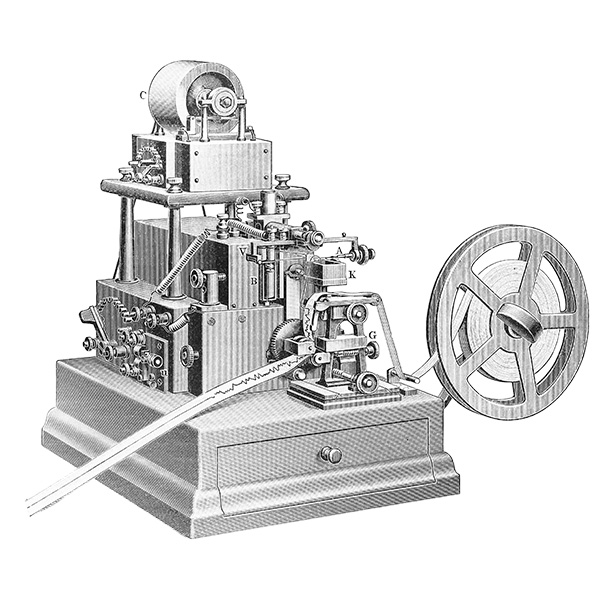

Within hours of when bullets were fired in Washington, DC, every New Yorker probably knew about it. Telegraph and newspaper offices in 1881 posted messages from telegrams onto schoolroom-sized chalkboards outside their doors, alerting city dwellers to the day’s happenings. For those on the farm, people gathered around railroad stations, which had telegraph lines running parallel to their rails. Society was growing accustomed to reading articles from other parts of the country in newspapers.

By 1861, when Lincoln was president, news services like the Associated Press transmitted dispatches along tens of thousands of miles of telegraph wires owned by Western Union that crisscrossed the nation. Since the Civil War, communications about battles and other faraway stories were commonplace, traveling along a web of wire from New York to Chicago to Cincinnati to St. Louis to New Orleans to California and all points in between. Newspapers pumped out stories, and a thirsty public drank them in.

When a New York Times headline stated “President Garfield Shot by an Assassin,” the nation was riveted because people revered Garfield. Although his presidency was only four months old, he had been a much beloved and popular orator since his days in Congress. As he fought for his life, Garfield saw support in broad swaths of the country — from certain immigrants in the Northeast, Black communities in the South, and settlers in the American West. Although Garfield was an abolitionist and targeted their livelihood, he believed in education and in enterprise. The news transmitted by telegraph about Garfield bonded these different groups together.

The next day, crowds stood at telegraph offices, several bodies deep, and were all relieved to see the message on the chalkboard: “A more hopeful feeling prevails.” The report further stated, “his temperature and respiration are now normal.” Garfield made it through the night. His spirits were buoyed when his wife arrived that evening, having pushed the limits of locomotives to reach him. Lucretia never left his bedside, and the crowds at the bulletin boards, growing in number, kept vigil, too.

From the White House, Garfield’s devoted private secretary, 23-year-old Joseph Stanley-Brown, had the unenviable job of sending telegraphed bulletins to the press, linking the nation to its leader. Bulletins were issued three times a day — in the morning, at noon, and in the evening — giving the status reports on the president’s condition. No detail was too dry or too dull. There were reports on how well Garfield slept, what he ate, and what his mood was. For the medically inclined, his temperature, pulse, and respiration were always reported. Most bulletins were short, alerting citizens that there was no appreciable change since the last bulletin, or that his condition was favorable.

There were reports on how well Garfield slept, what he ate, and what his mood was . . . No detail was too dry or too dull.

For the next few weeks, good news prevailed. From the bulletins, crowds learned that President Garfield was cheerful (July 7, 1881); had eaten “solid food” (July 17); was “comfortable and cheerful” (July 29); and had a pleasant nap (July 31). When Garfield had an operation near the bullet hole, doctors informed the public on July 24. These physicians believed that the bullet was a major source of Garfield’s trouble and were hell-bent on finding it. They even went so far as to solicit the help of Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone. Bell had also created a metal detector, which made a noise when metal was near it. Bell went to Garfield’s bedside in the White House on July 26, listening for the murmurs of where the lead slept. But the assassin’s bullet in the president’s torso could not be found.

News in the form of official bulletins continued to flow from the White House. On August 1, nearly a month after the attack, Garfield was “feeling better.” The president seemed to be recovering, and the nation’s hope swelled. There were a few weeks in early August when bulletins stated repeatedly that Garfield had “an excellent day,” and on one of them even mentioned that Garfield “slept sweetly.” The president was surprised by the nation’s response, retorting, “I should think the people would be tired of having me dished up to them in this way.”

But it was quite the opposite; the nation desired to know and to be in communication with its leader. From the day he was shot, “telegrams from all parts of the country and Europe kept pouring in at the White House,” reported the New York Times. After the Civil War, America was fractured, but updates sent along telegraph wires about Garfield helped fuse the nation back together.

August in DC in 1881 was hot, and as the temperatures rose, the country’s widespread concern for its leader in the oppressive heat rose, too. One bulletin on the morning of August 25 spoke directly to Americans, stating, “The subject of removal of the President from Washington at the present time was earnestly considered.” Garfield’s doctors wanted to get him out of the oppressive heat, and they also wanted to allay the public’s concern, but the president was too ill to move. Fever was always nearby, his face was now swollen with an infection of his salivary glands, and he had continual “gastric distress.” Garfield, who was a general during the Civil War, told his wife, “This fighting of disease is infinitely more horrible than battle.”

Garfield’s bulletin reports were mostly optimistic, but his actual prognosis was not. It was believed that the doctors wrote positive reports in the bulletins because Garfield asked to hear them, and they did not want to alarm him. The president looked at his charts and stated, “I have always had a keen appreciation of well-defined details and definite facts.” He studied his own case as if an outsider. But the words on the charts and in the bulletins and newspapers did a disservice, for a picture made it abundantly clear his imminent demise. Garfield, who was known for his girth at 210 pounds, withered to 130.

In early September, Garfield wanted to be moved to the New Jersey shore to be closer to the sea. Since he was a boy, he’d wanted to be a sailor, but his landlocked home state of Ohio didn’t offer much except work on the canals. Crowds lined the path of the train, and bulletins kept the public apprised, telling readers that he was eating well (September 11, 1881) and that his cough was better (September 12). By the 16th, his pulse fluctuated in the night. By the 18th, he had “severe chills” lasting an hour, perspiration, and was “quite weak.”

Garfield unwittingly united the public, catalyzing an obsession with news consumption that would come to define modern America.

In the evening of the next day, and without any warning, a bulletin on the 19th at 11:30 p.m. stated, “The President died at 10:35 p.m.” Only a few weeks shy of his 50th birthday, President James A. Garfield was dead, after battling infection from his wound for 79 days. The crowds surely wanted to know how he died, and the bulletin provided an answer with “severe pain above the region of his heart.” As his body lay in a bed in an oceanside town facing the sea he loved, the telegraph allowed the world to be at the president’s bedside.

Garfield didn’t live long as a president, but his influence on history, as he lay dying, was profound. His bravery was witnessed by millions of Americans, broadcast live along telegraph cables, making him a reality star of the Gilded Age. The New York Evening Mail said, “Lying patiently on a bed of suffering, he has conquered the whole civilized world.” Garfield knew his time left was short.

In September, on a still and contemplative night, he asked his close friend, Colonel Rockwell, “Do you think my name will have a place in human history?” Rockwell answered, “Yes,” reassuring Garfield that he’d live in “human hearts.” Garfield would indeed have an impact, but unlike what either of these men expected. He did not get an opportunity to transform the nation as president. But during the 79 days Garfield spent on his deathbed — the people’s patient — Garfield unwittingly united the public, catalyzing an obsession with news consumption that would come to define modern America.

Ainissa Ramirez, Ph.D., is best known as an award-winning science communicator dedicated to making science engaging for a broad audience. Dr. Ramirez began her career as a scientist at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey, and was later an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Yale. She is the author of several books, including “The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another,” from which this article is adapted.