How Fish Markets Transformed London’s Architectural Identity

Before the railway, the River Thames brought fresh fish into London markets via ice boats. Fish spoil quickly due to enzymes and bacteria, a process that is slowed by chilling. In England, the fishing fleets of Harwich began using ice to preserve fish at the end of the 18th century. The ice, collected in winter and stored in icehouses for several months, was instrumental in securing the time needed to bring fresh fish to urban markets, of which London was the most important. As London’s urban population swelled, so-called “wet” fish became a widely available, but expensive, alternative to cured fish. In fact, the capital was unique among British inland cities in its proportion of fishmongers to butchers, in part due to its size and centrality. In 1842, London had one fish dealer for every four butchers, whereas in Warwickshire the ratio was one to 27, in Staffordshire only one to 44.1 These relations would soon shift, propelled by the combined effect of urban growth, railways, and trawling.

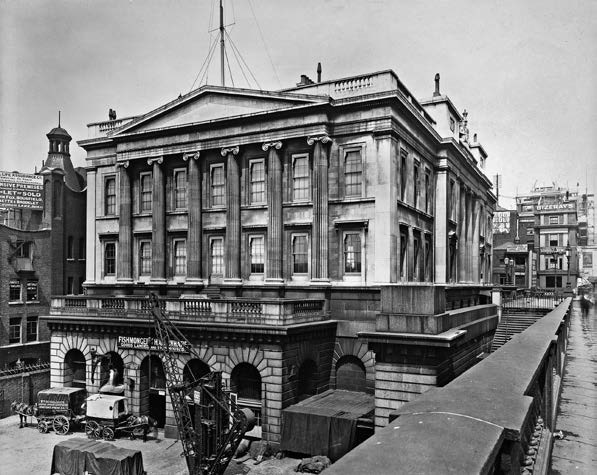

The first architectural sign of the prominence of fish in London was the Fishmongers’ Company Hall. The Fishmongers’ Company has administered the city’s fish trade since the 13th century, and with powers reinforced by a 1698 Act of Parliament, it secured the concentration of the trade in Billingsgate between the river and Lower Thames Street around Fish Street Hill. Its classical headquarters, just west of London Bridge, is worlds away from the frailty and vernacular character of most fishing facilities. Designed and built between 1831 and 1834 by Henry Roberts (1803–1876), at a time when George Gilbert Scott (1811–1878) was an apprentice in his office, the Hall’s monumentality inscribes it within a network of reputable urban institutions.2 Its dignified character does not connect it to fish or to the ecological and environmental contexts of fishing but rather reflects the social aspirations of the fishmongers. Their economic power, already visible in the 1830s before the Railway Mania of the 1840s, came from the growing consumption of fish products within the industrial city.

Billingsgate was a loud, frenzied area flavored by the odor of fish, with barges docked at piers that were extensions of city streets. Before the 1850s, when a proper market hall designed by James Bunning (1802–1863) was erected, fish were sold from a “group of sheds and stalls, accumulated no one knew how,” to use the words of a contemporary.3 The concentration of the city’s fish trade in a single location puzzled many contemporary chroniclers. But that concentration made sense given that the product was fresh fish. Fish supply is more unpredictable than other food items like meat and vegetables because of the nature of fisheries and their dependence on the ecological dynamics of marine environments. Variables such as seasonal trends, meteorological and navigational conditions, and the behavior of fish made the fresh fish trade a highly specialized niche with volatile prices. As a result, buying at the wholesale market — which adopted the frantic Dutch auction system, where the lot is sold to the first bidder at the highest price, instead of the last going up — required expert knowledge that discouraged direct trade between individuals or households and sellers. Instead, fish bought wholesale at Billingsgate was distributed to retailers in neighborhoods throughout the metropolis.

Market halls of the 19th century like Billingsgate’s replaced outdoor market squares. As architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner (1902–1983) noted, the new buildings were a curious hybrid of the railway station and the exhibition hall of an international fair.4 The central covered space was surrounded by stalls and galleries that made up the urban façade of the market and mediated between the street and the interior. An important innovation was the cast-iron roof structure developed in 1835 for Hungerford Market by Charles Fowler (1791–1867), who also designed the renovation of Covent Garden. Hungerford Market was one of various unsuccessful attempts to circumvent Billingsgate’s monopoly of the fish trade that likely failed because Billingsgate’s riverside location was better suited to the unique needs of fish supply.5 Ironically, the 1850s design for Billingsgate Market was a successful adaptation of Fowler’s type, as its longevity suggests: After being rebuilt in the 1870s, it remained open until 1982, when the wholesale market was moved east to Canary Wharf and the historic market building was converted to an office space by Richard Rogers (1933–2021).

In 1842, Charles Knight (1791–1873) wrote an atmospheric description of Billingsgate, dominated by the presence of fog and boats moored on the Thames: “The boats lie considerably below the level of the market, and the descent is by several ladders to a floating wharf, which rises and falls with the tide, and is therefore always on the same level as the boats.6 Fish would soon arrive by rail in increasing numbers.7 The statistics record 108 tons of water-borne fish in 1848 and 95 tons water-borne plus 71 tons rail-hauled in 1875. By 1910, the year the total tonnage reached its peak, 128 tons were rail-hauled and only 70 were water-borne. The tonnage of water-borne fish continued to drop between 1910 and 1936, when the supplying fleet was dismantled. But already in 1842 Knight insisted on the effects of railways providing fish supplies, not only to London but also to regions of England where fresh fish was not previously available: “In Leeds, Manchester, and Birmingham, during the summer of 1842, the supplies of fish, chiefly by the railways, were occasionally immense.”

One example of this new accessibility in 1842 was the Manchester shop opened by the Flamborough and Filey Bay Fishing Company. With the support of low transport rates and fast steam-powered trains, the shop would sell in the afternoon, at a competitive cost, fish landed overnight in the harbor of Hull. The low prices and novel product made the shop an immediate success, with demand exceeding supply and customers forming long queues. Numbers soared, the 3.5 tons of fish transported per week by the Manchester & Leeds line in 1841 grew to 80 tons in 1844, and other fishmongers and suppliers increased the flow of fish through the railway to the steadily increasing urban population.8 With the help of the extensive British railway system and the telegraph that allowed traders to ascertain the best deals throughout the distribution network, markets were connected to different fisheries, and London became the center of fish consumption, offering a combination of species harvested in various geographic locations. The historical southern harbors of the Channel, where sail trawling had been used for a long time, began to see competition from the new trawling fleets of the North Sea. The competition meant more supply to meet increasing demand from the growing urban population.

The first Billingsgate market building opened in August 1852. Designed by city architect James Bunning, it was an ingenious machine.9 First, a retaining wall was erected by the river, forming a terrace that expanded the available commercial surface. Public access was from Thames Street and led to the upper floor; the lower floor was connected to the riverside. George Dood describes the roof as “formed of semi-circular bays of corrugated iron, supported by iron pillars, and lighted by thick rough glass.” The market’s most prominent feature was the clock tower facing the river, the main purpose of which was ventilation. The mechanical system designed by Henry Bessemer (1813–1898) used “revolving pump-discs” to drain “the air from the lower vaults and market by suction, and propel it up the air-shaft enclosed within the clock-tower; by which contrivance it is said that 50,000 cubic feet of contaminated air can be expelled in a minute.” The water needed “for washing fish, washing hands, washing the market, and keeping everything neat and clean” was pumped directly from the Thames.10

Describing the London “of the poor” in 1851, Henry Mayhew provided a living portrait of the fish trade at Billingsgate. He emphasizes the role of railways, “by means of which fish can be sent from the coast to the capital with much greater rapidity, and therefore be received much fresher than was formerly the case” and the resulting transformation of fresh fish from an expensive product to a low-cost commodity:

This cheap food, through the agency of the costermongers, is conveyed to every poor man’s door, both in the thickly-crowded streets where the poor reside — a family at least in a room. … For all low-priced fish the poor are the costermongers’ best customers, and a fish diet seems becoming almost as common among the ill paid classes of London, as is a potato diet among the peasants of Ireland. Indeed, now, the fish season of the poor never, or rarely, knows an interruption. If fresh herrings are not in the market, there are sprats; and if not sprats, there are soles, or whitings, or mackarel, or plaice.11

The selection of available fish at Billingsgate Market “would enchant a Dutch painter” and reflected the diversity of marine resources conveyed to London.12 From the Atlantic waters of Cornwall to the North Sea harbors of Lincolnshire and Norfolk, such variety called for different prices and propelled new consumption habits. It was within this context that fried fish came to be Britain’s most popular takeaway food in the 20th century. Already in 1851 Mayhew counted between 250 and 350 fried-fish sellers in the vicinity of Billingsgate, transforming portions of sole and plaice into “shapeless brown lumps of fish.” Fish was chopped into indistinguishable chunks, battered with flour, and deep fried, which allowed it to be preserved and sold by street sellers distributing cheap food in poor neighborhoods.13

Price guided the trade, and as a fish fryer affirmed to Mayhew regarding which species he favored: “I buy whatever’s cheapest.” This was “the overplus of a fishmonger’s stock, of what he has not sold overnight, and does not care to offer for sale on the following morning.” The leftovers were classified as “fryers” and sold to costermongers to upcycle. The practice secured a minimum revenue for the fishmonger and created an innovative product for an extensive urban market. Unlike dried or pressed fish, fried fish did not require long hours of preparation and cooking. The working class now had access to a cheap, ready-made, and protein-rich food.

It was a perfect match between an uneven supply and a strong demand, and it soon defined entire city areas by the smell alone. The trade also gave rise to a new urban character, the fried-fish seller, who according to Mayhew typically had to live “in some out of the way alley, and not unfrequently in garrets; for among even the poorest class there are great objections to their being fellow-lodgers, on account of the odor from the frying.”14

Business at Billingsgate boomed so quickly that in 1877, just 25 years after the opening of the modern market hall, it had to be replaced by a larger building. This new market, still standing today, was designed by Horace Jones (1819–1887), who succeeded Bunning as city architect. The open central hall is roofed by an ingenious scheme of top-lit iron roof trusses that contrast with the more discrete load-bearing brick walls of the surrounding market galleries. Billingsgate’s distinctive working hours began at five o’clock in the morning, and by nine, the main business had been concluded. Several illustrations of the market interior show large oil lamps hovering over the stands, breaking through the obscurity of dawn by the Thames. But despite these facilities, critics were concerned with the hygienic condition of the building. Less than two decades after its opening, health associations complained that it was too small for its purpose and its sanitary conditions were “nothing more nor less than a disgrace”15:

Instead of all of the internal fittings being made of glazed, varnished, non-porous, non-absorbent materials, most of them are substances highly absorbent, which breed every form of germ bacteria or microbe, specially active in starting and ulcerating the decomposition or putrefaction of any dead fresh fish which may be in the market. Regardless of these concerns, and the harshness of the urban fish trade in the second half of the 19th century, fresh fish consumption continued to increase.

Fish and chips, the popular pairing of fried fish with fried potatoes, was perfectly aligned with the indiscriminate catches of trawling, and in the early 20th century the balance of supply and demand made it a long-term success, threatened only when frozen fish and new takeaway foods were introduced to the urban population. Particularly important, with regard to the ecological pressure placed on fish populations, was the adaptability of the technique of battering and frying to new varieties of fish, regardless of their palatable qualities. Because all fish can be fried, the popularity of fish and chips was great for the industry because it reduced offal and increased the profits of fishing, which was no longer required to target high-priced species.

With a new consumer culture came new ecological pressure. The growth of urban fish markets in the middle of the 19th century, facilitated by railway transport, was sustained by an increase in trawling and the development of new trawling technologies. The practice, which was not new, consists of towing a bag-shaped net along the seafloor. Trawling techniques varied widely depending on the type of vessel used, the nature of the seafloor, and the behavior of the targeted species. A leading harbor for trawling in the 1830s was Brixham on the English Channel in Devon, where wooden-hulled sailboats were the vessels of choice. The expansion of fish markets in the 1850s came with the exploitation of the rich fishing grounds of the North Sea, which moved the trawling centers from the Channel to older fishing communities such as Lowestoft and Yarmouth and to the newly developed harbors of Hull and Grimsby on the Humber River.

Several new technologies transformed the business. The first was the introduction of the mechanical capstan to wooden boats, which relieved fisherfolk from the hard effort of hauling a loaded trawl. As a result, boats could pull larger nets with smaller crews, operating faster over longer periods. Another innovation was steam power, which granted the boat independence in the face of variable winds. It also steadied the boat’s movement, and this, combined with inventive devices to keep the trawl open and rolling across the seafloor, made underwater harvesting more efficient than in the age of sail trawling, when wind and currents needed to cooperate. Finally, new steel-hulled vessels incorporated the previous advantages to become powerful trawling machines. With navigational improvements and operational advantages over older boats, the new vessels could take larger hauls over longer periods far from their landing harbor. As Callum Roberts pointed out, whereas the early “sailing trawlers were 20 to 30 tons burden,” those of the 1870s “were larger — 70 or 80 tons — longer and leaner and carried a much greater spread of canvas, lending speed and power.”16 Grimbsy and Hull were the harbors that best represented this “trawling revolution,” a change made possible by significant growth in the urban demand for fish.

André Tavares is an architect, Founding Director of Dafne Editora, and a researcher in the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Porto where he leads the project Fishing Architecture. He is the author of the books “The Anatomy of the Architectural Book,” “Vitruvius Without Text,” and “Architecture Follows Fish,” from which this article is excerpted.

- Charles Knight, ed., “London” (London: Charles Knight, 1842), 4:208

- Priscilla Metcalf, “The Halls of the Fishmongers’ Company: An Architectural History of a Riverside Site” (London: Phillimore, 1977).

- George Dood, “The Food of London” (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1856), 345. Bunning’s market hall was built by John Jay (1805–1872).

- Nikolaus Pevsner, “A History of Building Types (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 235-236

- George Dood, “The Food of London” (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1856), 345

- Charles Knight, ed., “London” (London: Charles Knight, 1843), 4:193–208.

- James Bird, “Billingsgate: A Central Metropolitan Market,” Geographical Journal 124, no. 4 (December 1958): 468. See also William John Passingham, “London’s Markets: Their Origin and History” (London: Sampson Low, Marston, 1935).

- Robb Robinson, “Trawling: The Rise and Fall of the British Trawl Fishery” (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1998), 27.

- Bunning’s most acclaimed building was the Coal Exchange, inaugurated in 1849, with a prominent cast-iron dome.

- George Dood, “The Food of London” (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1856), 347.

- Henry Mayhew, “London Labour and the London of the Poor: The Condition and Earnings of Those That Will Work, Cannot Work, and Will Not Work” (1851; London: Charles Griffin and Company, 1864), 64, 173–176.

- Charles Knight, ed., “London” (London: Charles Knight, 1842) 4:202

- John K. Walton, “Fish & Chips and the British Working Class,” 1870–1940 (London: Leicester University Press, 1992); Panikos Panayi, “Fish and Chips: A Takeaway History” (London: Reaktion Books, 2014)

- Henry Mayhew, “London Labour and the London of the Poor: The Condition and Earnings of Those That Will Work, Cannot Work, and Will Not Work” (1851; London: Charles Griffin and Company, 1864), 174.

- “The Insanitary Condition of Billingsgate,” British Medical Journal 1, no. 1524 (March 15, 1890): 616

- Callum Roberts, “The Unnatural History of the Sea: The Past and the Future of Humanity and Fishing” (London: Gaia, 2007), 146