How Coca-Cola’s Calories-Out Myth Backfired Spectacularly

In 2009, Rhona Applebaum had a problem. As more researchers were revealing the health risks of sugar-sweetened beverages, concerns about obesity were threatening the business model of her employer, Coca-Cola. Per-capita soda consumption had actually begun declining in the United States. Applebaum felt the diet side of the obesity equation had been getting too much attention, and the exercise side too little.

Applebaum had a plan. What if Coca-Cola designed a program to emphasize exercise over diet? What if the corporation designed and structured it, and partnered with the nation’s largest physical fitness organizations — the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the National Strength and Conditioning Association — to promote it? Why not call it Exercise Is Medicine?

It would be an audacious scheme. Americans were surely savvy enough to know they should not be getting training information from a soda company. Or maybe not.

Applebaum was more than just another soda operative; she was a scientist with gravitas. She boasted a bachelor’s degree from Wilson College, an MS in nutrition and food science from Drexel University, and a PhD in food microbiology from the University of Wisconsin.

She had served on the Science Board — an advisory committee of the FDA — and chaired an influential panel in the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. All this was in addition to advisory work for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Applebaum’s scientific bona fides were impeccable, and she’d spent three decades in the food industry. She had risen to the post of vice president and chief scientific and regulatory officer for Coca-Cola. And she was leading the corporation’s Beverage Institute for Health and Wellness.

In the fall of 2009, Applebaum was organizing an event at a nutrition conference in Bangkok. The event would be called “Exercise Is Medicine — A Global Initiative to Improve Public Health.” Trying to line up speakers for the event, she reached out to University of Colorado obesity researcher James Hill. “My POV — it’s time the ‘calories-out’ side of the [equation] was given more prominence at these nutrition/health [meetings],” Applebaum wrote to Hill. Applebaum offered to introduce the Exercise Is Medicine program. She also asked University of South Carolina obesity expert Steven Blair for his help in organizing.

It was an auspicious beginning. Exercise Is Medicine would not only conquer the United States; it would soon have projects all over the world.

In late May, the San Diego Convention Center was bustling with health and fitness experts. The occasion was the annual meeting of the ACSM.

Jim Hill, the University of Colorado obesity expert, delivered the keynote speech. He used the opportunity to introduce the Global Energy Balance Network (GEBN), a campaign promoting the erroneous notion that maintaining a healthy body weight is simply a matter of burning as many calories as you consume. His white hair neat, glasses stylish but unobtrusive, sporting a yellow power tie and a blue blazer, Hill spoke from a lectern bearing a plaque reading, “World Congress on Exercise Is Medicine.”

The gist of his talk was that the calories-out side of the equation deserves more attention. But he’d refined some of his talking points. To emphasize the role of tech-induced inactivity, he said, “I oftentimes say that Bill Gates is responsible for as much obesity as Ronald McDonald.”

Americans were surely savvy enough to know they should not be getting training information from a soda company. Or maybe not.

The ACSM had long and deep ties to soda. Two of its past presidents, Russell Pate and Steven Blair, were involved with the large Coca-Cola–funded study at the University of South Carolina, and had spoken forcefully on the corporation’s behalf.

The San Diego conference was purportedly a health event, but the soda industry had its fingerprints all over it. It was not just soda’s longtime role in funding the American College of Sports Medicine; the conference program also noted that Coca-Cola was a founding partner of Exercise Is Medicine.

The event was the confluence of several streams of Coca-Cola funding, but hardly anyone knew it at the time. One person who understood this, Greg Glassman, founder of the CrossFit fitness empire, was in the audience, seething at the soda links.

A couple of months after watching Jim Hill’s talk in San Diego, CrossFit’s Greg Glassman sounded off about the (GEBN) with a typically profane tweet: “@CocaCola’s @gebnetwk trolls for ‘scientists’ to make a case for hiding metabolic syndrome w/ exercise. Watch @ACSMNews suck the soda tit!” Then he added this to the tweet: “@EIMNews is the lobbying arm of a deadly idea, @gebnetwk. Such @CocaCola projects aim to silence all who warn about sugar. #CrossFit.”

A self-made millionaire, opinionated and unfiltered, Glassman had become a prominent soda industry critic. Partly it was his anti-sugar, low-carb dietary stance. And partly it was a long-time feud with the ACSM and the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA), another mainstream fitness group. Glassman felt both had been working to stymie his fast-growing fitness company and were aligned with and funded by Coke and Pepsi.

In his tweet, CrossFit was taking on not just Coca-Cola but also the ACSM and Exercise Is Medicine (EIM), its partnership with Coke. It wasn’t a big deal, really. It was retweeted just fourteen times. But the tweets were the first public shots across the bow.

Meanwhile, Glassman and his CrossFit team were taking their soda critiques directly to their network of fitness aficionados. In mid-July, at the District CrossFit gym in DC, several dozen athletes watched from folding chairs as Glassman worked a whiteboard like a professor. The subject was arcane: a bill passed by the District of Columbia to require the licensing of personal trainers.

The whiteboard soon became cluttered. The top line read “District licensure bill.” Below that was a confusing array of shorthand and acronyms. There was the NSCA and ACSM, Glassman’s longtime foes. Beneath that, the GEBN and EIM. You definitely needed the whiteboard to follow along, but the nut of Glassman’s talk was simple: a cabal of mainstream fitness groups was out to destroy CrossFit. “They want oversight,” he told the CrossFitters. “They want to control you, license you, regulate you.” To an outsider, it might have seemed altogether paranoid. What might any of these organizations and food corporations want to do with CrossFit? An organized effort by a government agency to take over the business of fitness?

Glassman walked through the items, one by one. “Exercise is Medicine, that’s another soda thing,” he said. “Guess what its first aim is — so you wonder, does soda want to get you? — guess what its number one stated goal is. The licensure of trainers. Now why does soda give a fuck about whether trainers are licensed or not? I’ll tell you why. Because they want to separate them. And they want to legally separate them. They want to get the ones that, like, ‘It’s all exercise,’ and won’t talk about the soda. And then get the ones like you that are going to say, ‘It’s the sugar.’

In other words, Glassman was saying that if the licensure bill passed, the mainstream fitness groups could incorporate Exercise Is Medicine ideology into training programs, and CrossFit instructors who criticized sugar would be disenfranchised.

“They want to make what you do illegal. It will be. See, this is Coke and Pepsi again,” Glassman said, tapping the whiteboard. “You have to understand that when exercise is medicine, what happens in here will then be medical malpractice.”

“You have to understand that when exercise is medicine, what happens in here will then be medical malpractice.”

As Glassman wrote on the whiteboard, he occasionally checked facts with Russ Greene, sitting off to his side, likely the only person in the room who understood the whole diagram. A CrossFit employee, Greene had been blogging prodigiously about the soda industry’s influence on the mainstream fitness organizations that were CrossFit’s competitors. He took to the task with the aggressiveness of a pit bull and the rigor of an investigative journalist.

Glassman developed momentum, striding back and forth in his favorite camo Henry’s Coffee ball cap, worn backward, and a pair of faded jeans. “You feel it? Put your hand up and show me if you’re hearing what I’m saying,” Glassman said, holding his hand high, revealing the sweat ring on his turquoise T-shirt. “Is anyone pissed? Alright, you oughta be. I mean what they want — whatever you used to do, they want you to go back to doing that.”

Walking back to the whiteboard, he tapped the letters ACSM. “And they are perfectly willing to require that you employ some asshole from this organization and pay her to stand over there in the corner and watch you and report, ‘He’s talking that anti-sugar stuff again. Unh, unh, unh, Global Energy Balance Network, you know that he’s just not exercising enough,” Glassman said.

Taken as a whole, it shaped the outlines of a crazy plot. And Glassman’s conspiracy theories and shoot-from-the-hip tweets would, in five years, contribute to his downfall. But the scheme Glassman was detailing — Coca-Cola’s orchestration of the Global Energy Balance Network — would soon be validated by the mainstream media.

The New York Times headline on August 10 was dramatic: “Coca-Cola Funds Effort to Alter Obesity Battle.” And the front-page scoop by Anahad O’Connor was powerful: “The beverage giant has teamed up with influential scientists who are advancing this message in medical journals, at conferences and through social media,” wrote O’Connor. “To help the scientists get the word out, Coke has provided financial and logistical support to a new nonprofit organization called the Global Energy Balance Network, which promotes the argument that weight-conscious Americans are overly fixated on how much they eat and drink while not paying enough attention to exercise.” O’Connor reported that the GEBN was rooted in $1.5 million of undisclosed funding from Coca-Cola.

The fallout from O’Connor’s piece was swift and powerful. Longtime soda critic Michael Jacobson wrote a letter to the editor calling the GEBN “scientific nonsense.” It was co-signed by Walter Willett of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, along with thirty-four other researchers, academics, and advocates.

The New York Times followed up with an editorial. It noted that the network, which promised to deliver unbiased science, would likely not. It cited an analysis in PLOS Medicine that found that “studies financed by Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, the American Beverage Association and the sugar industry were five times more likely to find no link between sugary drinks and weight gain than studies reporting no industry sponsorship or financial conflicts of interest.” Within just a few days, Coca-Cola had gone from being a corporation that hoped to host a journalistic roundtable on pseudoscience to being the exemplar of the practice.

Coca-Cola CEO Muhtar Kent was aware of the network’s efforts. After all, only a year earlier, he had been working with Rhona Applebaum to get Jim Hill a slot on Charlie Rose’s CBS show. But Kent did not defend the program. Instead, he penned a very public apology in the Wall Street Journal, promising, “We’ll do better.” He wrote, “I am disappointed that some actions we have taken to fund scientific research and health and well-being programs have served only to create more confusion and mistrust. I know our company can do a better job engaging both the public-health and scientific communities — and we will.”

Coca-Cola soon launched a transparency website in an effort to disclose its health research and partnerships. It listed a total of $119 million doled out over five years. The usual suspects were prominent. The University of Toronto soda ally John Sievenpiper alone was credited with receiving $273,000.

The list would be an embarrassment for many in the health sciences, including the ACSM, the nonprofit that collaborated with Coke to found Exercise Is Medicine. The ACSM preemptively notified its members: “It has come to our attention that, in response to recent news, The Coca-Cola Company will soon publicly disclose the health and well-being partnerships it has recently funded.”

Coca-Cola’s millions had bought undying loyalty, even from obesity experts.

Coca-Cola had funded ACSM with $865,000. And Steven Blair — the University of South Carolina cofounder of the GEBN — had been awarded more than $4 million in funding.

The exposé took many by surprise, but not Russ Greene. He noted that Blair had also once served as the president of ACSM and was on the advisory board of Exercise Is Medicine. “So if we add Blair’s total to the previous number,” Greene wrote in a blog post, “Coca-Cola has paid ACSM and its officials at least $6,342,000 in the past five years.” And, presciently, Greene noted that Coca-Cola had omitted a significant amount of funding from the list.

For more than a year, Greene had been writing about soda-funded corruption of the health sciences. At first, it had seemed an improbable bit of collusion. But with the exposé of the network, it began to look as though he had not overstated the degree of the problem, and may even have underestimated it.

Following the New York Times exposé, Coca-Cola’s GEBN unraveled strand by strand. Coca-Cola had originally claimed that it did not control the group’s research and publications. But Associated Press reporter Candice Choi uncovered more emails, making it clear that Coca-Cola designed and controlled every aspect of the group and even exerted influence over the research.

CEO Muhtar Kent, who had already apologized in the Wall Street Journal, expressed more contrition still. Kent told Choi, “It has become clear to us that there was not a sufficient level of transparency with regard to the company’s involvement with the Global Energy Balance Network. . . . Clearly we have more work to do to reflect the values of this great company in all that we do.”

The network disbanded. The University of Colorado returned $1 million in research funds to Coca-Cola. Organizations like the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Academy of Pediatrics stopped accepting Coca-Cola’s money. The University of South Carolina, on the other hand, opted to keep $500,000 of Coca-Cola money.

In addition, the emails showed that Coca-Cola’s millions had bought undying loyalty, even from obesity experts. In a note to Coke, Jim Hill had written, “It is not fair that Coca-Cola is [singled] out as the #1 villain in the obesity world, but that is the situation and makes this your issue whether you like it or not. I want to help your company avoid the image of being a problem in [people’s] lives and back to being a company that brings important and fun things to them.”

US Right to Know, a nonprofit that did yeoman’s work in finding documents through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, pointed out how effectively Rhona Applebaum’s network had used journalists. The organization listed thirty articles that quoted Blair and Hill after they received funds from Coca-Cola, but without citing the relationship. Some were by known Coca-Cola allies, but others were by mainstream journalists with some of the nation’s largest media outlets: the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, NPR, the New York Times, and the Washington Post. Another consequence of the Times exposé is that Applebaum became the public face of pseudoscience. She soon tendered her resignation to Coca-Cola, the inglorious end to a once-impressive career.

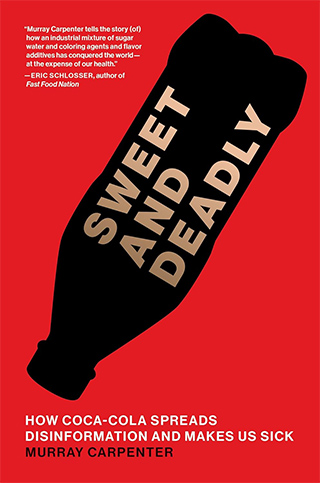

Murray Carpenter has worked as a print and radio journalist in Maine for 25 years, and has reported for the New York Times, NPR, and the Washington Post. He is the author of two books, including “Sweet and Deadly: How Coca‑Cola Spreads Disinformation and Makes Us Sick,” from which this article is adapted.