How Actors Remember Their Lines

After a recent theater performance, I remained in the audience as the actors assembled on stage to discuss the current play and the upcoming production that they were rehearsing. Because each actor had many lines to remember, my curiosity led me to ask a question they frequently hear: “How do you learn all of those lines?”

Actors face the demanding task of learning their lines with great precision, but they rarely do so by rote repetition. They did not, they said, sit down with a script and recite their lines until they knew them by heart. Repeating items over and over, called maintenance rehearsal, is not the most effective strategy for remembering. Instead, actors engage in elaborative rehearsal, focusing their attention on the meaning of the material and associating it with information they already know. Actors study the script, trying to understand their character and seeing how their lines relate to that character. In describing these elaborative processes, the actors assembled that evening offered sound advice for effective remembering.

Similarly, when psychologists Helga and Tony Noice surveyed actors on how they learn their lines, they found that actors search for meaning in the script, rather than memorizing lines. The actors imagine the character in each scene, adopt the character’s perspective, relate new material to the character’s background, and try to match the character’s mood. Script lines are carefully analyzed to understand the character’s motivation. This deep understanding of a script is achieved by actors asking goal-directed questions, such as “Am I angry with her when I say this?” Later, during a performance, this deep understanding provides the context for the lines to be recalled naturally, rather than recited from a memorized text. In his book “Acting in Film,” actor Michael Caine described this process well:

You must be able to stand there not thinking of that line. You take it off the other actor’s face. Otherwise, for your next line, you’re not listening and not free to respond naturally, to act spontaneously.

This same process of learning and remembering lines by deep understanding enabled a septuagenarian actor to recite all 10,565 lines of Milton’s epic poem, “Paradise Lost.” At the age of 58, John Basinger began studying this poem as a form of mental activity to accompany his physical activity at the gym, each time adding more lines to what he had already learned. Eight years later, he had committed the entire poem to memory, reciting it over three days. When I tested him at age 74, giving him randomly drawn couplets from the poem and asking him to recite the next ten lines, his recall was nearly flawless. Yet, he did not accomplish this feat through mindless repetition. In the course of studying the poem, he came to a deep understanding of Milton. Said Basinger:

During the incessant repetition of Milton’s words, I really began to listen to them, and every now and then as the poem began to take shape in my mind, an insight would come, an understanding, a delicious possibility.

In describing how they remember their lines, actors are telling us an important truth about memory — deep understanding promotes long-lasting memories.

A Memory Strategy for Everyone

Deep understanding involves focusing your attention on the underlying meaning of an item or event, and each of us can use this strategy to enhance everyday retention. In picking up an apple at the grocers, for example, you can look at its color and size, you can say its name, and you can think of its nutritional value and use in a favorite recipe. Focusing on these visual, acoustic, and conceptual aspects of the apple correspond to shallow, moderate, and deep levels of processing, and the depth of processing that is devoted to an item or event affects its memorability. Memory is typically enhanced when we engage in deep processing that provides meaning for an item or event, rather than shallow processing. Given a list of common nouns to read, people recall more words on a surprise memory test if they previously attended to the meaning of each word than if they focused on each word’s font or sound.

Deep, elaborative processing enhances understanding by relating something you are trying to learn to things you already known. Retention is enhanced because elaboration produces more meaningful associations than does shallow processing — links that can serve as potential cues for later remembering. For example, your ease of recalling the name of a specific dwarf in Walt Disney’s animated film, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” depends on the cue and its associated meaning:

Try to recall the name of the dwarf that begins with the letter B.

People often have a hard time coming up with the correct name with this cue because many common names begin with the letter B and all of them are wrong. Try it again with a more meaningful cue:

Recall the name of the dwarf whose name is synonymous with shyness.

If you know the Disney film, this time the answer is easy. Meaningful associations help us remember, and elaborative processing produces more semantic associations than does shallow processing. This is why the meaningful cue produces the name Bashful.

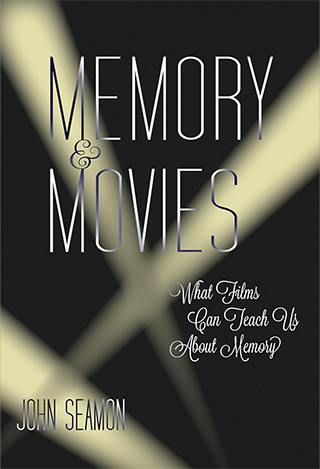

John Seamon is Emeritus Professor of Psychology and Professor of Neuroscience and Behavior at Wesleyan University. He is the author of “Memory and Movies: What Films Can Teach Us About Memory,” from which this article is excerpted.