An Art of the Room: The Haunting Installations of the 1980s

It was in the 1980s that installation truly emerged as an art form in its own right, a different way of thinking about objects and space.

But how do we define “installation art,” a term used so sloppily? For me, it is best thought of as an art of the room. An art where, above all else, as Christian Boltanski put it, “the spectator’s body is inside the work.” Artists such as Boltanski, Ann Hamilton, and Ilya Kabakov wanted viewers not only to have a deeper physical relationship with the material world, phenomenologically, but also to become more aware of the historical and cultural associations that places and things carry with them.

These artists had a heightened sense of place, of how the context always becomes part of the meaning. In a world in which people were moving around more and more, the need for a deeper sense of a particular place — home or otherwise — was becoming a craving. “An installation,” said Hamilton, “surrounds you, absorbs you into it. You are part of it the minute you step into it.” You, the visitor, or any object in an installation, cannot help but become part of what she refers to as the skin. “It’s like the interior/exterior condition we live within our bodies — the skin creates illusions of separation, but it’s a permeable membrane that goes both ways.”

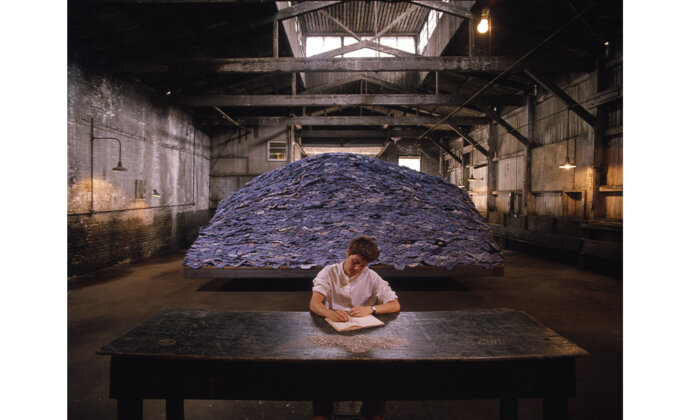

In 1991 Hamilton took part in “Places with a Past,” an exhibition of site-specific works in Charleston, South Carolina — a city of beautiful 18th-century houses, often described as the capital of the old South. Hamilton, however, chose to make her installation in a disused garage; and rather than research the kind of “nostalgic” history liked by tourists, she read about labor conditions. Discovering that the dark-blue dye indigo had been crucial to the city’s manufacturers, she ordered more than six tons of used blue work clothes — some 48,000 trousers or shirts. These clothes, she realized, had all been worn by people who had been laid off, or whose employers had gone bust.

Most installations were ceremonial rather than domestic. They were places where your emotions were engaged, where something might happen — a site or rite of passage.

As always in Hamilton’s installations, everything was touched by hand. She and her assistants carefully folded the clothes before placing them on a large metal platform, creating a stack 18 feet tall. If you had visited the old garage during her installation, you would have found behind this mound of clothes a person sitting at a desk, rubbing out the words in books with blue covers. (Hamilton often gets someone to perform some such task, giving her work motion and life.) You would also have been able to look down on the installation from an office. Inside this office were hung, as Hamilton describes, “udder-sized net bags of soybeans which sprouted and later rotted in the leakage of summer rains. With the humid weather, the space was filled with the musty smell of the damp clothes and the organic decomposition of the soybeans.”

Why did installation emerge as a major practice in the 1980s? Artists were becoming increasingly concerned with how and where their work was installed. Minimal sculpture especially made you intensely aware of the environment the object inhabited, so it was inevitable that minimalist artist Donald Judd and others would start to focus on the space, the room. Judd exemplified this approach, using a military base in Marfa, Texas, as a site for art. But installation art such as Hamilton’s was often very far from minimal.

Above all else, as I said earlier, installation art is an art of the room or interior; it is no coincidence that the rise of such art came at the same time as the success of such magazines as The World of Interiors. Most installations, though, were ceremonial rather than domestic. They were places where your emotions were engaged, where something might happen — a site or rite of passage. The experience, as Hamilton always emphasized, was rooted in your body moving in an environment and experiencing with all your senses: sight, hearing, touch (often), smell (frequently), taste (occasionally) and always that almost unconscious sixth sense of your body moving through space — what neurologists call proprioception, and which can also be called kinaesthesia. You had to physically be there to have this experience. Like so much contemporary art, installations are an attack on the ubiquity of reproduction, especially photographic reproduction. Neither my words nor the pictures on the page can replicate the experience of being there. All they can do is give a faint, distorted echo.

Among the early work of Christian Boltanski — all supposedly made in response to memories of childhood traumas — were hundreds of tiny handmade objects, balls of dirt or small knives, arranged in the sort of glass vitrines one sees in museums, or else collections of banal photographs of people who were not famous, arranged across walls or in photo albums. It was only in the 1980s, when the artist was in his 40s, that he began to take over whole rooms, often darkening them to heighten the mood.

It was vital for Boltanski that these clothes were second-hand and that they smelt, smelt of people who were no longer there.

In 1989, for example, when asked to make a work in the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Boltanski chose to show not in one of the galleries but in two forgotten and rather dilapidated basement rooms. Entering these windowless spaces, you initially came across a grid of 55 enlarged but blurred photographs of children who had died, illuminated only by small lamps above. Then you encountered, first with your nose and then with your eyes, a room filled with metal shelves piled high with clothes. (It was vital for Boltanski that these clothes were second-hand and that they smelt, smelt of people who were no longer there.) Clearly, this was about memory, death and the archive.

It is difficult for anyone familiar with European history not to be reminded of the rooms filled with discarded clothes found at Auschwitz and the death camps. Indeed, by the end of the 1980s, Boltanski would admit that the Holocaust was always on his mind: His father had been Jewish, and was apparently hunted by the Nazis, although Boltanski saw himself as more Christian than Jewish. “My work is not about the camps, it is after the camps,” he explained. “The reality of the Occident was changed by the Holocaust. We can no longer see anything without seeing that. But my work is really not about the Holocaust, it’s about death in general, about all of our deaths.”

What does a museum get when it buys an installation by Boltanski? Maybe some shelves, some lamps, some old clothes; maybe some photographs of dead people. But what happens if the shelves do not fit the room? Or the lamps die? Or the clothes rot? Or the photographs fade? Just get new ones, suggests Boltanski; it is the idea that matters, not the objects per se. They are not holy relics. Boltanski believes that what he is doing is providing a musical score, as composers do, which needs to be reinterpreted each time the piece is staged.

If, as I did, you had visited the old pavilion of the Soviet Union at the 1993 Venice Biennale, you might have thought it was closed up. It was surrounded by a rough wooden fence. “Oh well,” you might have said to yourself, “the USSR has disintegrated so nothing will be happening here.” But if you had noticed an arrow pointing to a gap in the fence, you might have gone through that gap and into the pavilion. There was no exhibition to see, just scaffolding, piles of wood and the smell of construction — dust, paint and newly sawn timber. Ha, you would have thought, this could be a metaphor for Russia itself: fallen apart, but not yet reconstructed. Then you would have heard some tinny music in the distance, and decided to go to the back of the pavilion, where there is a good view of Venice and its lagoon. Once there, you would have realized that, yes, I have been in an exhibition, and yes, it was a metaphor! For there in the garden you would have seen a small building festooned with red flags and Soviet emblems, the three loudspeakers suspended above its roof blaring out the songs and marches once heard at the May Day parades on Red Square.

“If an installation is properly made, you can’t leave without going through a whole cycle of emotions. You lose your sense of time.”

Maybe it would have made you nostalgic for a more optimistic time, one now lost. Or perhaps you would have had the same thoughts as Ilya Kabakov, who had set this up: “This ‘little pavilion’ is the territory of a world which has not disappeared anywhere, but is only hidden, concealing itself behind the back of another,” read a press release for the installation. “Standing in the depths of the courtyard, it is merely waiting for its own hour so that it may return to the place from which it was recently expelled.” Expectation, walking, smell, music, the light on the waves, surprise, memories, reflection were all part of both the experience and the work. As Kabakov said in 1994: “If an installation is properly made, you can’t leave without going through a whole cycle of emotions. You lose your sense of time.”

Before 1989, Kabakov had been an “unofficial” artist, making a living in his native Soviet Union as an illustrator of children’s books. “In Russia,” he insisted in a conversation with art critic Boris Groys, “being involved in art was for me a vital, existential thing, not a professional endeavor.” But after leaving Russia in 1992 and moving to New York, he became a “professional” artist, albeit one whose subject was always the USSR, its institutions and communal apartments. Sometimes he would describe it as hell, but would recreate it with apparent nostalgia. The many objects that went into what he called his “total installations” were not important; it was the atmosphere that mattered.

At its best, installation was a way not only of embedding the visitor’s body and mind in the actual artwork, and in the material world, but also of engaging with history — not in the sense of dry facts noted in a book, but as lived, or remembered, experience.

Tony Godfrey is the author of “Conceptual Painting,” “Painting Today,” and “The Story of Contemporary Art,” from which this article was excerpted. He has contributed to Art in America and the Burlington Magazine. Formerly Programme Director of the MA in Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute in London, he is a curator based in Manila.