Frescoes in the Desert: Alois Musil and the Rewriting of Islamic Pasts

Imagine seeing something that comes as a great surprise and changes your overall understanding of what is available as evidence of the past. It makes you think that your colleagues would benefit from knowing about it too. But when you present it to them in words, they refuse to believe you, saying that either you are making it up or you were mistaken in interpreting what you saw. To take you seriously, they demand visual proof, which you then provide after being disappointed by their initial reaction. What you finally bring to visual attention becomes a crucial component of the story told about Islam in modern scholarship.

The scenario I have outlined is a part of the self-narrative of Alois Musil (d. 1944), an intrepid Moravian-Czech Catholic priest who trained as an orientalist and spent many years traveling in the Arabian peninsula and neighboring regions. Musil’s vast output includes the 1898 “discovery” of Qusayr ‘Amra (now Jordan), a bathhouse with elaborate and unusual frescoes on its walls next to some ruins. I put the word discovery in quotation marks because Musil was led to the sight of the bathhouse by residents of the local desert who well knew the place and what was in it long before Musil’s arrival. The sense that something new became visible via Musil pertains only to its availability for orientalist knowledge of Islam that is now a part of the standard historical view.

Musil’s story instantiates the difference between objects as they exist, and knowledge of them, that is a constitutive part of the modern history of Islamic art. Like all art history, the field depends on the visual domain: It requires seeing materials that have been placed in museums or for which images are available that can be put in books or on the web. Objects associated with Islam were produced over many centuries, for reasons ranging between utility and luxury, without any necessary reference to what is considered art in modern contexts. To understand them as “Islamic art” is an idea that solidified in the late 19th century in close conjunction with the establishment of the timeline version of the Islamic past that I attempt to rethink in “A New Vision for Islamic Pasts and Futures.”

The sense that something new became visible via Musil pertains only to its availability for orientalist knowledge of Islam that is now a part of the standard historical view.

Multiple hypotheses have been put forth to explain Qusayr ‘Amra’s frescoes. Rather than considering the site in the vein of art history or archaeology, I am concerned primarily with what people have thought to have seen in the frescoes. This exercise illuminates how visible forms have been correlated to chronologies to feed into the construction of the Islamic past. Qusayr ‘Amra is especially valuable because it originated in the eighth century CE and falls within the earliest material evidence we have for a society associated with Islam.

Visual Evidence of Early Islam

At the time he came across Qusayr ‘Amra, Musil was a junior scholar exploring in lands associated with the Bible and Islam’s birth with sponsorship from the Austro-Hungarian empire’s grand academic establishment centered in Vienna. His first encounter with the site was very short, enough for him to realize it was extraordinary but without enough time for careful examination. He then left the region abruptly, so his first communications about the site were based on verbal and very limited visual evidence.

The first published comment on Qusayr ‘Amra occurs in the bimonthly Arabic journal al-Mashriq (The East) run by Jesuit academics in Beirut. The July 15, 1898, issue contains excerpts from a letter from Musil received in Beirut detailing his travels in the Arabian peninsula and Palestine. The portion of the reproduced letter does not mention Qusayr ‘Amra, although it describes other related ruins he says he has visited in the company of Bedouin hosts. We can presume that the letter did say something about Qusayr ‘Amra because an article by Henri Lammens in the same issue of the journal contains a photograph of the building, with attribution to Musil, and refers to it by name as belonging in a group of buildings come to light lately.

Lammens’s 1898 article in al-Mashriq provides the first modern interpretation of Qusayr ‘Amra. He argues that the bathhouse must be seen as a part of the building program of the Ghassanids, an Arab dynasty aligned with the Byzantines that was a major power in the Levant until the region’s Muslim takeover in the middle of the seventh century. The key issue is that Qusayr ‘Amra is given a pre-Islamic provenance. Musil may have agreed with Lammens in the beginning, but further research, undertaken after returning to Europe, inclined him to think the site had been built by the Umayyads, an Islamic dynasty, during the first half of the eighth century.

Source: Belvedere Museum, Vienna, Austria

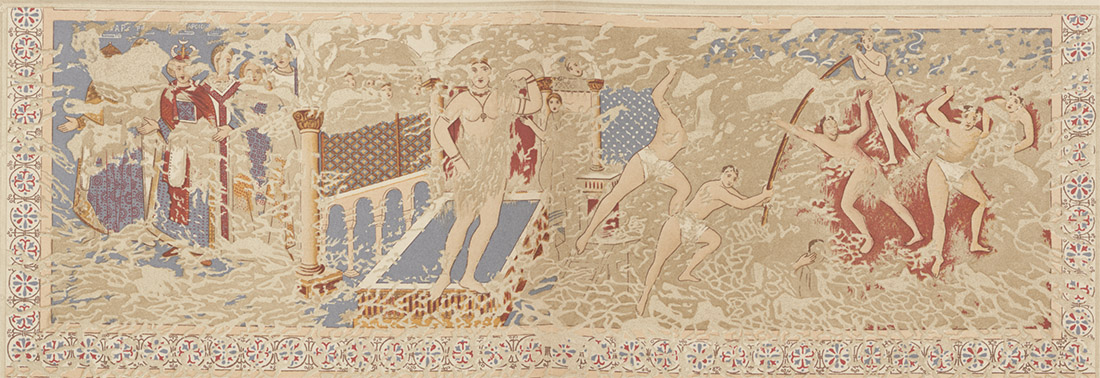

While Lammens took Musil’s evidence seriously enough to write about it, the discoverer’s first presentations of the site in Vienna were met with skepticism that such a site, with a dating close to the birth of Islam, could even exist. However, the possibility was enticing enough that he was able to secure funding and go back to the site in 1901 to collect proof. This time he was accompanied by the painter Alphons Mielich (d. 1929), who had spent considerable time in the Middle East already and had made a name for himself as an orientalist painter. The 1901 expedition by Musil and Mielich resulted in a two-volume publication on Qusayr ‘Amra in 1907 that included academic articles by various European experts and reproductions of Mielich’s paintings of the frescoes done on site. These volumes canonized the site, although the interpretations provided in them were affected greatly by various scholars’ prior intellectual commitments as well as professional jealousy and competition. Most interestingly, this work laid out the argument that Qusayr ‘Amra should be seen as a late antique monument, hence not Islamic, and even older than the Ghassanid-Arab provenance suggested by Lammens. This attribution stemmed from stylistic analysis under the influence of Alois Reigl, a famous scholar associated with the position that art history’s disciplinary specificity resided in tracking time through forms rather than textual references.

Affected greatly by Mielich’s vision of the frescoes as represented in painted replications, modern scholarship on Qusayr ‘Amra until the 1950s placed it varyingly between the fifth and eighth centuries CE. The variation is noteworthy because it hinges on alternative hypotheses regarding the relationship between forms and the chronology of Islam for which the frescoes were as intriguing as they were challenging. As more Arabic text on the site became visible, however, it became certain that the frescoes were of an Umayyad provenance. This made Qusayr ‘Amra a foundational monument for “Islamic art” and turned the frescoes into a different sort of problem to be resolved.

When Musil and Mielich undertook their work on site in 1901, they subjected the frescoes to harsh chemical treatments and scrubbing, also detaching some parts from the walls that were carted away to Europe and were eventually sold to museums. Long after these initial attempts, Spanish and French teams undertook systematic restorative work in the 1970s and 1980s, some of which included overpainting and other enhancement techniques that amounted to significant alteration.

In parallel with the physical changes, interpretive glosses applied to the site also started thickening from the 1950s onward. The main imperative has been to explain it in terms that make sense in view of presuming that the Umayyads were Islamic actors. Oleg Grabar concentrated on the site as a part of his dissertation in the 1950s, from which he presented it as an Umayyad princely monument meant for pleasure. Garth Fowden’s work then expanded this view in a 2004 book that uses a vast range of late antique and Arabic sources. In a 1993 article, Grabar indicated that his earlier interpretation may have been based on problematic presumptions.

I will dwell on Fowden’s interpretation first since it is, in effect, an expansion of Grabar’s original view and represents the mainstream of Islamic art history on how material evidence should be interpreted. Fowden’s self-consciously orientalist positioning is evident from his book’s preface: He begins with a quotation from the British imperial agent T. E. Lawrence, presents Musil as the first person to have set eyes on the monument (since the eyes of the Bedouins who took Musil to the site were irrelevant), and likens himself to one of Lawrence’s men.

Fowden’s main interest is to account for Qusayr ‘Amra as an Islamic place, where his sense is that, of course, he already knows Islam’s essence based on his knowledge of the Quran and other textual sources. The task is straightforward with respect to some parts of the frescoes: for example, an image known as the “six kings” in which a royal figure is shown receiving homage from other kings, who are identifiable as powers in the world (most prominently the Byzantine and Sassanid emperors) based on iconography and explicit labeling in both Arabic and Greek scripts. This cashes out as an example of supercession: An Umayyad ruling authority dominates over other rival or defeated political regimes.

A more vexing issue for Fowden is how to make sense of the large number of female figures, many of them nude, in the frescoes. He is certain that Muslims should not be in the habit of representing such things because of statements in the Quran and other authoritative sources. Attempting to solve this problem leads Fowden to take a deep dive into late antique material and textual sources as well as the archive of Arabic literature seeking parallels for what is found in the frescoes. On this basis, he provides extensive hypotheses regarding Qusayr ‘Amra being a multipurpose royal monument whose frescoes instantiate expression of political power and eroticism in idioms relatable to, on the one hand, prior material culture and, on the other, conventions of Arabic poetry.

In Oleg Grabar’s reconsidered reflection, noticing the variety makes it equally plausible to regard the place as meant for powerful women as for men committed to ogling female bodies.

Impressive as Fowden’s work is, it suffers from the methodological problem that the parallels are spread widely among antecedents and later examples, all chosen without detailed assessments of the rhetorical contexts in which they occur. The analysis selects wherever convenient on the basis of a predetermined argument while ignoring counterexamples and logical inconsistencies. While Fowden’s familiarity with a vast range of sources is amply on view, its analytical purchase amounts to little more than affirming orientalist presumptions about Islam and Muslims that can be tracked to the 19th century. Fowden’s work mirrors too the mainstream of Islamic art history where scholars first presume what Islam is and then winnow through evidence selectively to reaffirm the initial proposition. In this mode, no evidence can actually shake the established view of Islam. In the case of what is visible at Qusayr ‘Amra, for example, an argument could be made that the frescoes should make us fundamentally rethink what we presume to be the norms and ideals of those (Muslims) who made or sponsored the frescoes. Rather than being an empty vessel conveying a sui generis Islam, perhaps the monument destabilizes the concreteness accorded Islam in literary materials that are Fowden’s major sources. Prominently, Fowden’s overwhelming reliance on elite poetry stands against the fact that there is no poetry to be found at the site. Fowden presumes, without providing an explanation regarding specific data, that “aesthetic” expression can be understood as a single corpus across media and forms.

Contrary to Fowden’s position, late in his career, Oleg Grabar recognized that he may have been wrong to seek singular explanations and total coherence when interpreting sites such as Qusayr ‘Amra. The recourse to texts, especially poetry, may have overdetermined the site’s meaning. In his article “Umayyad Palaces Reconsidered,” he remarks that on the subject of the depiction of women (a topic that has been a permanent titillation for modern Western scholarship on Islam), the site contains a wide variety of images: “Sensuous performances cohabit with highly proper ones, possible narratives coexist with apparent scenes of leisure and domestic life, and trite personifications are found alongside concrete references.”

In Grabar’s reconsidered reflection, noticing the variety makes it equally plausible to regard the place as meant for powerful women as for men committed to ogling female bodies. The shift in visual perspective opens the topic in a way that is beyond Fowden’s confident assertion of highly speculative hypotheses as the only plausible explanations for the site.

Reconsidering the Frescoes

Two developments during the first two decades of the 21st century have made way for a major shift in the discussion of what is visible at Qusayr ‘Amra. One of these has to do with work on the physical site and the other with interpretation. Between 2010 and 2013, a team of Jordanian and Italian experts restored the frescoes at Qusayr ‘Amra. This work included removing smoke debris, overpainting from previous restorations, and carefully surveying the various layers of marks that can be seen. A major discovery from this was an Arabic inscription identifying an Umayyad prince as the site’s patron, confirming what had been presumed by most recent observers. This restoration also made details of the frescoes more clearly visible than was ever possible before. On the interpretive side, recent scholarship on the Umayyads has shown that the view of the dynasty as wastrels devoted to pleasure alone is a case of accepting at face value the views of their rivals, such as the Abbasids who supplanted them.

This shift is an automatic challenge to the interpretation of Qusayr ‘Amra as a hedonistic palace. In this vein, Nadia Ali’s recent work (“Qusayr ‘Amra and the Continuity of Post-Classical Art in Early Islam,” featured in the volume “The Diversity of Classical Architecture”) urges close attention to the specifics of the frescoes at Qusayr ‘Amra and cognate monuments. She shows, for example, that images placed inside a grid on the frescoes on the central ceiling belong to “an agricultural calendar inspired by post-classical imagery, thus challenging the traditional narrative on Umayyad palatial art and providing a striking case of how the explanatory power of texts has been overestimated in the previous scholarship on Qusayr ‘Amra.”

Photo 127887340 © Dmitry Chulov | Dreamstime.com

Unlike Fowden’s method, Ali’s work is attentive to both the forms of the images and their organization based on a very specific context of usage. This approach makes the further important point that the monument should not be reduced to being the effect of a single agent such as a pleasure-loving royal patron. In addition to the sponsoring Umayyad prince, its form was conditioned by the knowledge, cosmology, aspirations, and aesthetic expectations of the craftspeople who created the frescoes. If we see Qusayr ‘Amra and the larger corpus that is the subject of Islamic art in this way, visual evidence has the potential to deconstruct the rhetorically unifying image of Islam we get from literary sources. Rather than considering them to be problems to be solved based on an Islam we already know, the frescoes of Qusayr ‘Amra may contain a key to a radically deessentializing approach to Islam via attention to material culture.

Recent restoration efforts at Qusayr ‘Amra also show there is more to the site than its construction in the eighth century CE and discovery by Musil in 1898. The smoke residue that had partially obscured the frescoes came from fires lit inside by visitors seeking shelter over the centuries. Moreover, the walls contain graffiti in the form of people’s names and dates of visits in 1329–1330, 1345–1346, 1409–1410, 1442–1443, and so on. In addition to these snippets of text, the walls of Qusayr ‘Amra contain a profusion of tribal marks (known in Arabic as wasm) that point to local inhabitants’ use of the building. These marks are summary indications of complex Bedouin histories preserved in local communities through oral means during all the centuries the building has existed. The building has an entirely different history, not yet fully explored, when seen from the eyes of locals.

The building has an entirely different history, not yet fully explored, when seen from the eyes of locals.

In addition to his association with Qusayr ‘Amra, Alois Musil is known for his extensive knowledge of Bedouin lore that he accumulated while developing deep bonds with peoples living in the area surrounding the monument. For the point I am making here, it is instructive to contrast between what he and the locals saw in the frescoes. The Bedouins, all of them identifying as Muslims, knew of the frescoes and took Musil to them. Although acutely invested in the pasts of their communities, they clearly did not consider the frescoes a part of their own valuable past.

However, what had no value for local Muslims’ understanding of Islam was to prove transformative for the modern academic view of the material remains of the Islamic past. Although existing at the same time and present in the same spaces, Musil and his Bedouin hosts were invested in utterly different chronological schemes when it came to understanding Islam. The variety we can document easily for this context is a model for how we should think about the original makers of the frescoes as well as our own appreciation of multiplicity within Islamic pasts.

Shahzad Bashir is Aga Khan Professor of Islamic Humanities and Professor of History and Religious Studies at Brown University. He is the author of, among other books, “A New Vision for Islamic Pasts and Futures,” from which this article is excerpted.

Works Cited:

Ali, Nadia. “Qusayr ‘Amra and the Continuity of Post-Classical Art in Early Islam: Towards an Iconology of Forms.” In The Diversity of Classical Archaeology, edited by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2017.

Fowden, Garth. Qusayr ‘Amra: Art and the Umayyad Elite in Late Antique Syria. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Grabar, Oleg. “Umayyad Palaces Reconsidered.” Ars Orientalis 23 (1993): 93–108.

Lammens, Henry. “Aqdam athar li-Bani Ghassan.” al-Mashriq 1, no. 14 (1898): 630–637.

Lash, Ahmad. “Kitabat ‘ala judran Qusayr ‘Amra al-Umawi.” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 58 (2014): 7–36.

Musil, Alois et al. Kusejr ʻAmra: Mit Einer Karte von Arabia Petraea. Vienna: K. K. Hof- Und Staatsdruckerei, 1907.

Musil, Alois. “Rihla haditha ila bilad al-badiya.” al-Mashriq 1, no. 14 (1898): 625–630.