‘Eliminate the nonessential’ and Other Advice for Artists

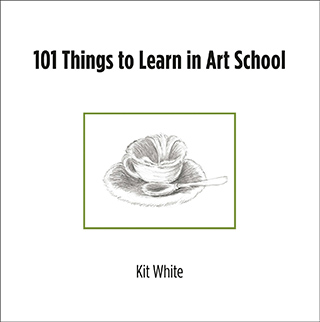

“Art is an idea that belongs to everyone,” writes artist and teacher Kit White in the opening pages of his book “101 Things to Learn in Art School.” “Whatever physical form it might take, whatever emotional, aesthetic, or psychological challenge it may offer, it is vital to every culture’s sense of itself.” As such, art is not separate from life, says White, but the very description of the lives we lead.

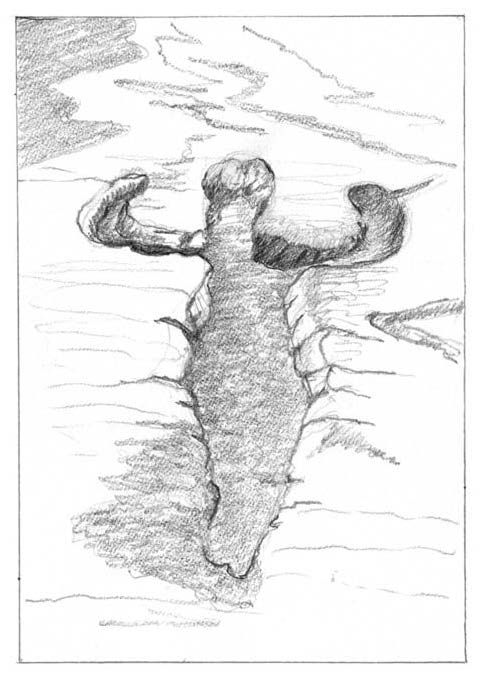

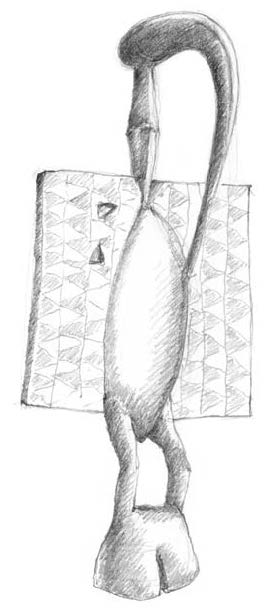

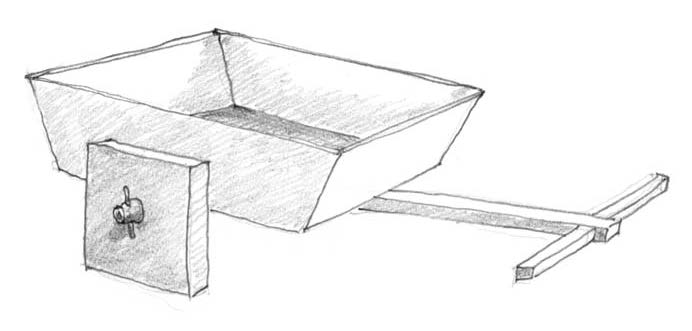

The 101 maxims, meditations, and demonstrations contained in White’s book offer both a toolkit of ideas and a set of guiding principles for the artist. Complementing each of the 101 succinct texts is an expressive drawing by the author, often based on a historical or contemporary work of art, offering a visual correlative to the written thought. “Art can be anything” is illustrated by a drawing of Duchamp’s famous urinal; a description of chiaroscuro art is illuminated by an image “after Caravaggio”; a lesson on time and media is accompanied by a view of a Jenny Holzer projection; advice about surviving a critique gains resonance from Piero della Francesca’s arrow-pierced Saint Sebastian. “101 Things to Learn in Art School” is a guide to understanding art as a description of the world we live in, and using art as a medium for thought. We’re pleased to offer a selection of lessons from the book below.

—The Editors

For every hour of making, spend an hour of looking and thinking.

Good work reveals itself slowly. You cannot judge a work’s full impact without hours of observation. It is also a good idea to step away from what you are doing at regular intervals. The immediate impression a work makes when it is reencountered is critical. A good work is satisfying both upon immediate encounter and after long periods of concentrated viewing. If any work fails on either approach, keep trying until you feel satisfied that you have succeeded on both counts.

Making art is an act of discovery.

If you are dealing only with what you know, you may not be doing your job. When you discover something new, or surprise yourself, you are engaging in the process of discovery.

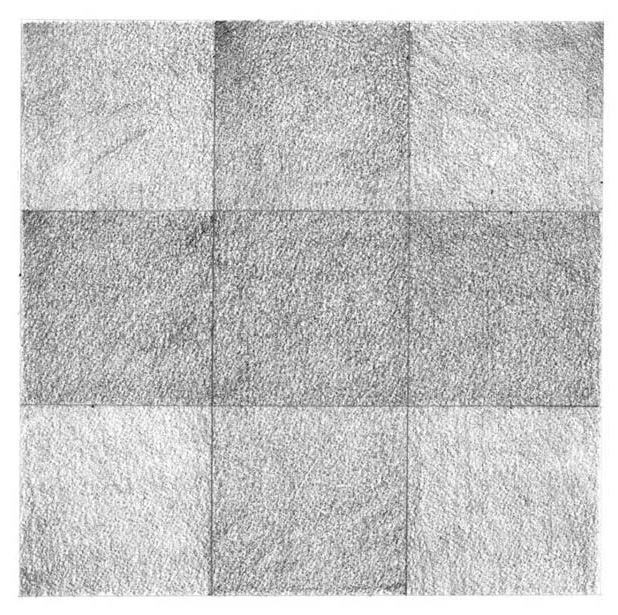

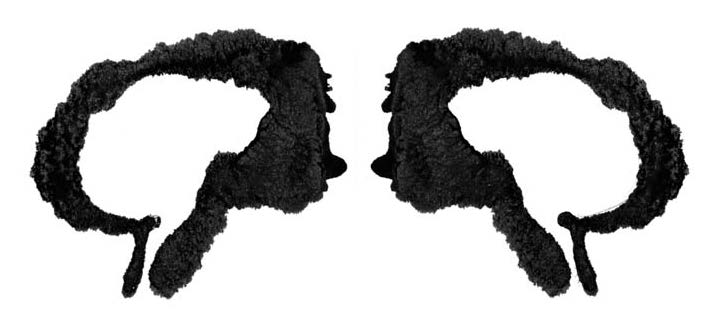

The human brain is hardwired for pattern recognition.

It has the capacity to distinguish tens of thousands of variations of the human face, which is composed of slight differences in a small set of features. The brain looks for what it knows. This has an upside and a downside. It makes it possible to create a recognizable image with very crude means. But it also makes it more difficult to render the world new or unfamiliar. To make an image different enough to bypass the brain’s pattern recognition and force it to reassess the meaning of an image is a challenge for every artist. To make the familiar unfamiliar is a large part of making new visual language.

Art is a form of experimentation.

But most experiments fail. Do not be afraid of those failures. Embrace them. Without courting the possibility of something miscarrying, you may not take the risks necessary to expand beyond habitual ways of thinking and working. Most great advances are the product of discovery, not premeditation. Failed experiments lead to unexpected revelations.

Color is not neutral.

It has an emotional component. Certain colors have specific associations and induce certain responses. Learn what they are. When you use color, try to determine and understand the accompanying emotional response and how to use it effectively. Color has a visceral impact.

Meaning does not exist in the singular.

It is a transaction between two or more conscious minds. Your work is an attempt to bridge understanding between you and others. For this reason, there is no such thing as private symbolism. Meaning derives from communication.

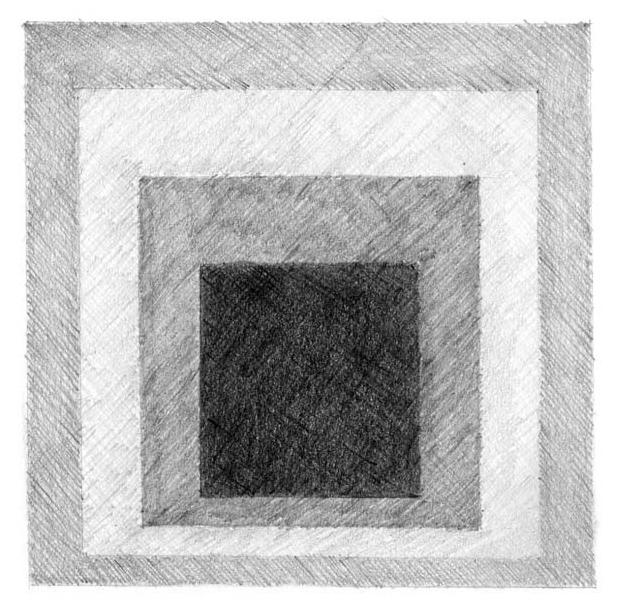

Eliminate the nonessential.

Every work of art should contain whatever it needs to fulfill its descriptive objective but nothing more. Look at the “leftover” parts of every composition. Successful images have no dead spaces or inactive parts. Look at your compositions holistically and make sure that every element advances the purposes of the whole.

An idea is only as good as its execution.

It is important that you master your medium. Poorly made work will either ruin a good idea or make the lamentable execution itself the subject. Overly finessed technique can mask a lack of content or can smother an image. At the same time, roughness and imprecision has its place in rendering. One can only gauge the need to throw technique away if one has first achieved the mastery of it.

Kit White is an artist and former professor of painting at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn. His work is in the permanent collections of many museums, including the Guggenheim Museum. He is the author of “101 Things to Learn in Art School,” from which this article is excerpted.