Genetic Ancestry Doesn’t Tell Your Whole Story

Genetic ancestry is a concept that has long captured people’s imaginations. It’s no surprise that it’s been turned into a booming industry by companies like 23andMe and Ancestry.com.

Customers of genetic testing can now be delighted to learn that they’re “southern European,” “East Asian,” “British Irish,” “Greek and Balkan,” or “sub-Saharan African.” Others might be fascinated with claims of their “Viking” or “Yamnaya” roots and, upon discovering them, come to believe these revelations are central to their identities.

However, the inconvenient truth is that these labels and identities are, for the most part, meaningless in historical, cultural, and even genetic terms. Having ancestry found in Viking genomes does not really make you “part Viking.” The reason for this is simple: Population genetics is not a perfect science.

What we call “ancestry” is merely an approximation of genetic similarity to specific reference populations. These reference populations are artificial constructs used by scientists for modeling. They are often based on ancient genomes from different archaeological and chronological periods that are intended to represent particular populations (e.g., “Steppe nomads,” “Romans,” “Slavs,” or “Anglo-Saxons”). But these labels are neither universal nor objective; they’re selected arbitrarily and can, to some extent, determine the perceived outcome of the analysis.

Having ancestry found in Viking genomes does not really make you “part Viking.”

Perhaps the most significant issue with such categories is that they ignore the profound impact of human mobility over the last few hundred years, creating an impression of genetic fixation. These categories suggest that human populations stayed in place throughout world history, allowing each to develop highly distinct genetic compositions.

However, ancient genomics indicates that migrations have, instead, been constant throughout human history. From the Out-of-Africa migration 60,000-70,000 years ago to the Atlantic Slave Trade beginning in the 16th Century, mobility — not isolation — has always been the norm. Because of this movement and mixing, geographic connection to present-day individuals in a particular country can be deceptive. Genetic similarity might, then, reflect shared ancestry from hundreds or thousands of years ago, in a region far removed from where someone lives today.

At first blush, humans seem an incredibly diverse species. We vary in skin color, sex, sexuality, gender identity, hair and eye color, height, weight, limb length, face shape, and disease resistance, among other things.

Yet, despite our visible differences, you’ll be surprised to learn that we are among the least diverse species in the world. Humans share about 99.9 percent of our genomes, meaning that two randomly chosen individuals differ in an exceedingly tiny fraction of the chemical building blocks of our genome. Because of this overwhelming similarity, defining what constitutes a population is not easy. The boundaries can be expanded or contracted, making the concept notoriously difficult to pin down objectively.

In population genetics, a population is defined as a group of individuals that mate with one another and are, to some extent, distinct from other groups. These populations are sometimes characterized by their cultural or geographic traits (for instance, speaking a different language from neighboring groups, or being restricted to an island or to the boundaries of a nation).

However, in the case of humans, there are no truly isolated populations. For practical reasons, some scientists have chosen to work solely with nationalities, while others have chosen to work exclusively with cultural attributes. But each approach has its own limitations. (Imagine trying to compare individuals from Iceland, which is relatively small and homogenous, with a geographically immense and diverse Russia.) Ultimately, the different definitions of populations depend on the questions posed and the genetic data under review.

In the natural world, well-defined genetic populations are found. That’s because there are geographically restricted populations or species that are completely isolated from others. Examples include Madagascar lemurs and the extinct dodo from Mauritius. In these cases, known as “endemism,” the largest population of a species defines its range limit.

Yet that is virtually impossible to find in modern humans; we are all genealogically connected to some extent as we trace our ancestry back in time. And while people have adapted to specific environmental conditions in the last tens of thousands of years — producing geographic patterns of variation in traits like skin pigmentation or pathogen-resistance genes — that patterning is merely an illusion.

The very concept of race, for instance, arises from pigmentation genes, which are evident only because of how populations are distributed around the world. But these apparent patterns have been disproven by genomic studies. Indeed, whole-genome analyses indicate gradual variation across regions rather than fixed racial categories.

In genetics, scientists must analyze the genomes of millions, if not billions, of people, each carrying millions of variants. It’s an unfathomable amount of data. Which leads us to another central blind spot in genetic ancestry research: how we, as scientists, visualize the sheer scale and complexity of human genetic variation.

Traditional representations, such as phylogenetic genetic trees, shed no light on this crucial aspect of human genetics. This explains why some population labels have been progressively abandoned: According to the archives of the American Journal of Human Genetics, the use of “Caucasian” in papers declined from 12 percent around the mid-20th Century to less than 1 percent at the beginning of the 21st Century. Alongside this decline, continental labels have increased — for instance, the use of “European” surged to 42 percent of papers between 2009 and 2018.

Genetic ancestry is not a definitive marker of identity; it’s just one part of a much bigger puzzle,

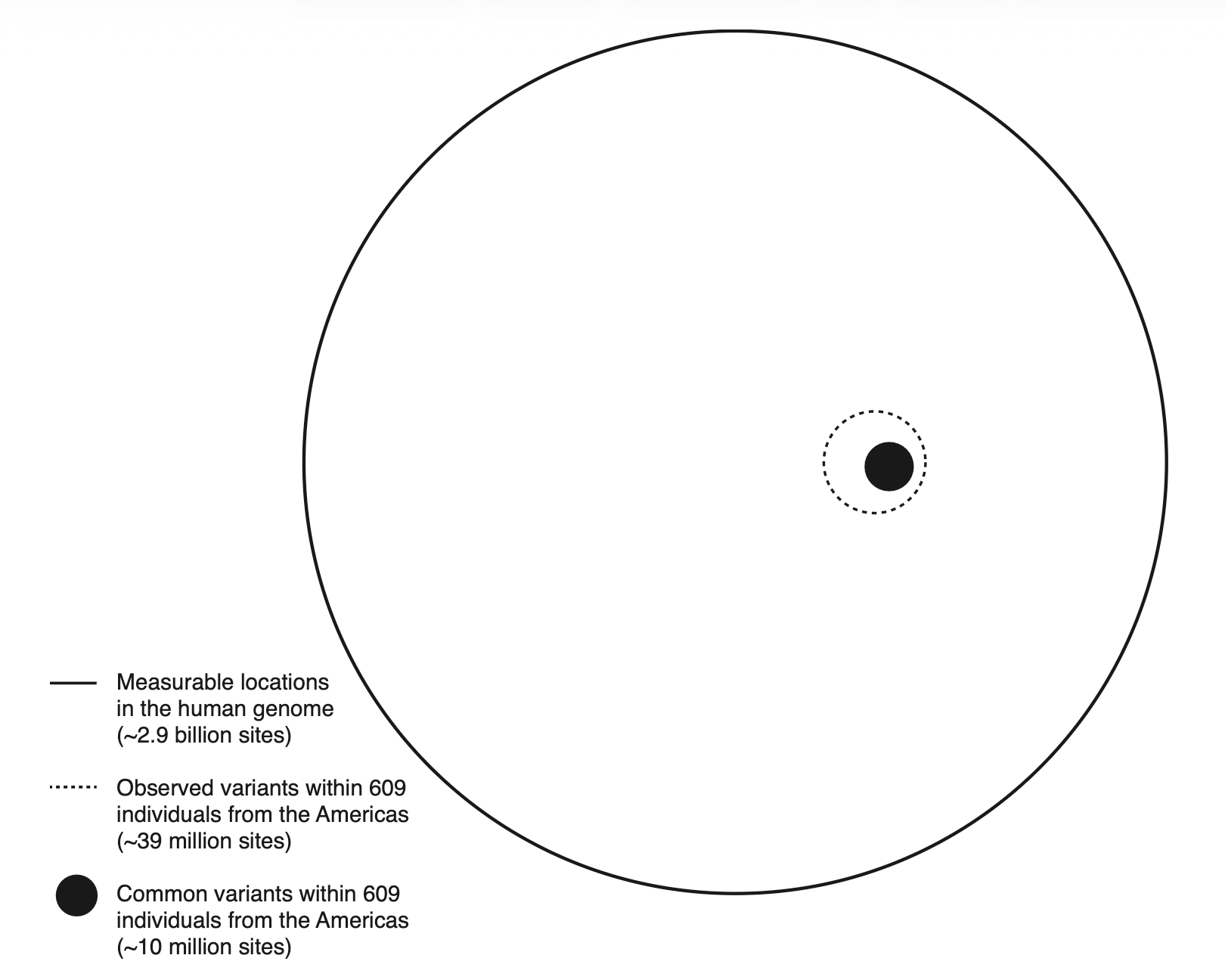

Recently, instead of trees, geneticists have proposed representing genetic ancestry as overlapping circles. Starting with approximately 2.9 billion measurable nucleotide sites that can vary across the human genome, geneticists James Kitchens and Graham Coop, for example, analyzed a sample of 609 individuals from the Americas and found only 39 million observable variants. If they restricted the analysis to those genetic variants defined as “common,” the number of sites decreased to 10 million, an almost insignificant fraction of the potentially general number.

The researchers repeated the approach across different populations, invariably finding remarkably few variable sites relative to the total genome length. For instance, 99 Utah residents with northern and western European ancestry exhibited 5,726,377 variants, whereas 96 African Caribbeans from Barbados exhibited 8,018,649 (the latter likely reflects the greater genetic diversity in Africa). More importantly, across populations, the degree of overlap in common variants is enormous, which means human groups have few exclusive genetic variants. In fact, variants that are common in a single geographic region are usually not exclusive to that region; they are present at similar frequencies in other populations worldwide.

This is all to say that the complex interplay between ancestry and population differences undermines the idea of race as a real biological category. People don’t share a single, uniform genetic background with others in their community. Instead, populations — however we define them — have slightly different proportions of ancestry components.

Instead of imagining abstract models of past populations, ancient genetics allows us to refer to specific sites and archaeological time periods from which a particular skeleton originated. Genetic ancestry is not a definitive marker of identity; it’s just one part of a much bigger puzzle, offering what I believe is a richer foundation for thinking about our collective identity and shared past.

Carles Lalueza-Fox is a leading research expert on the retrieval and analysis of ancient genomes, including extinct hominins, past human populations, and pathogens. He is Director of the Natural Sciences Museum of Barcelona and the author of several books, including “Identity: What DNA Can Tell Us About Ourselves,” from which this article is adapted.