Crossing Borders, Imagining Heimat: On Art and Home

Parastou Forouhar was born in Tehran in 1962. She arrived in Germany in 1991 to study at the Offenbach Academy of Art, near Frankfurt, where she now lives and works. Her work consists of drawings, books, and installations, many of which incorporate black Persian calligraphy. She has commented that her writing is a search for her Heimat, her homeland.

Heimat is a key German term, suggesting rootedness in a particular place and its traditions and customs, one’s place of comfort and belonging in the world. The glossary of the essential anthology of writings on German diversity, “Germany in Transit: Nation and Migration, 1955–2005,” defines the typical understanding of Heimat and its iconographic and genre associations: “Native land, homeland, or home. This untranslatable German word connotes romantic yearning for a sense of belonging and suggests pastoral landscapes and regionalism, as in Heimatfilm.” As historian Alon Confino has contended, “Germans like to think of the Heimat idea as unfathomable, mysterious, and, above all peculiarly German.” In fact, as he has shown, Heimat is yet another “invented tradition,” to borrow the famous phrase and concept from political scientist Benedict Anderson.

Throughout Germany after 1880, similar iconography and tropes — woods, fields, mountains — became associated with diverse localities that were each designated as a unique Heimat, that irreplaceable place of origin and desired return. The “Heimat idea” thus derived less from each of those specific individual places having some very specific hallmarks than from Germany’s general drive to create a national identity that could be invoked throughout the new and fractured nation.

People who would not fit comfortably within and would, at best, complicate such Heimat imagery — historically, Jews in Germany; today, people “with a migration background” — often refer to multiple homelands. The acerbic German Jewish writer Henryk Broder has written: “The big problem with Heimat, it seems to me, is that a person is expected to choose one. It would be better simply not to have one. Or best of all: to have a whole lot of them.” Burcu Dogramaci comes to a similar conclusion in the last line of her book studying the term and the concept of Heimat in contemporary art: “The question posed by the writer Max Frisch, with which this book began, ‘How much Heimat do you need?’ can by this logic only have one answer: Many Heimats, More than I can count.”

“… my Heimat has grown invisibly and beautifully in my thoughts. I search for it in the script of my mother tongue…”

For Parastou Forouhar the use of Persian (or Farsi) calligraphic script, covering walls and floors, and written onto table tennis balls distributed throughout the installations, creates her one imaginary and imagined home. Her parents, Parveneh and Dariush Forouhar, were prominent secular dissidents in Iran, and were assassinated in their home in 1998. If she were to return to Iran, she would be subject to imprisonment. Unable to return to that Heimat, she imagines and creates homes in language. In her statement for the catalogue of the 2000 exhibition Heimat Kunst, she ruminated on the concept of Heimat and her use of Persian in relation to it:

I am a Persian woman. I can tell wonderful stories about my homeland (Heimat), that may not be true. I have wonderful memories of my country, and don’t know if I have manipulated them. Sometime, and I don’t know exactly when, I began to construct an imaginary castle out of the term, “Heimat.” And since then my Heimat has grown invisibly and beautifully in my thoughts. I search for it in the script of my mother tongue, that spreads gently and rhythmically and invitingly with the openness and indifference of the beautiful Persian forms left behind by the old masters from past centuries.

Like the work of historians such as Confino and Celia Applegate, Forouhar’s work challenges both the idea of Heimat as specifically German and of its existence outside systems of representation, of which language is a primary example.

Farkhondeh Shahroudi is another artist with Iranian origins but long in Germany, based in Berlin, and working with Farsi and German — and, unusually, not English. Born in Tehran in 1962, Shahroudi arrived in Germany in 1990, and received political asylum. Her website states, in English: “After studying painting at the University Al-Zahra in Tehran, followed by art and design at the University of Dortmund, she directed her research to one in which the use of textile materials and sewing became predominant, in a constant dialog with her poetic writing, which she has always practiced and considers the primary font of her artistic expression.”

She writes her stream-of-consciousness poems in German and Farsi, and incorporates them into performances, many of which are collective, involving participants in the spirit of Allan Kaprow’s happenings. When writing in German, though, she writes with her left hand, which makes her more conscious of her body’s investment in translating the linguistic impulses emanating from her mind.

In 2017 Shahroudi was a fellow at the storied Florentine Villa Romano, founded as a German cultural institution by artist Max Klinger in 1905. While she was there, Shahroudi, who claims that all of her work derives from her unconscious, engaged in dialogue with the ghost of an earlier fellow, Max Beckmann, who painted his self-confident “Self-Portrait in Florence” there in 1907. The pink-cheeked young man in the black suit looks confidently out of the painting at the viewer, holding his white cigarette at a downward angle in his right hand, as if it might be the brush with which he applied the loose strokes of paint that form the background to his more solidly articulated form.

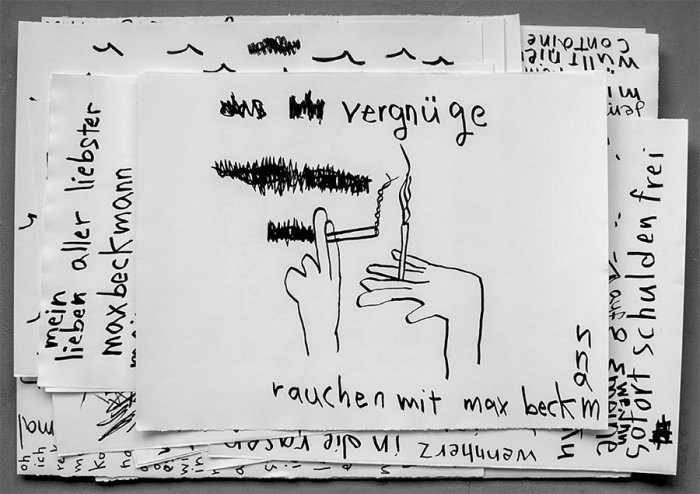

Returning to her studio in Berlin-Wedding, Shahroudi initiated a series of poem-drawings on paper and on the wall of the studio declaring “max beckmann war nicht hier” (max beckmann was not here), establishing her own hegemony in that space, linguistically exorcising herself from Beckmann’s ghost, and perhaps alluding to her own exile in Germany through Beckmann’s from Nazi Germany. In one left-handed drawing, though, she refers to Beckmann’s 1907 self-portrait, inserting her own vertically oriented hand next to his horizontal one, while her horizontal cigarette reaches toward his vertical one. The text declares that she “enjoys smoking with max beckmann.” Elements in the drawing are placed under erasure, forming free-floating signifiers hovering on the surface of the drawing.

Returning to Iran, she commissioned a banner with traditional Persian embroidery defining the corners and her liberating phrase, “max beckmann was not here,” emblazoned in bright red letters in German. Hung on the outside wall beneath her studio’s windows, it recalls the signage on buildings occupied by squatters, even as it declares her studio never to have been occupied by Beckmann. The pleasantly colored and decorated banner seems more appropriate to a celebration than a protest march or occupation: Perhaps with such a celebratory performance Shahroudi’s spectral Beckmann will finally go up in smoke.

On July 14, 2018, Shahroudi staged the participatory performance “Wave Anti-Flag Demo” in the English Garden in Munich as part of the inaugural en plein air performance festival organized by curator Emily Barsi. The group created “flags” out of woven hair and carried them through the park. Such flags connect directly with the material of humanity, unmediated by state affiliations. Shahroudi also read from a stack of her poems. These had been written with her left hand; she distributed them to participants to read from her wobbly script. She held aloft signs with words that cut across borders, that through their sound (onomatopoeia) have meaning in a variety of languages, such as “Oh” and “Ah” and “Wow.”

Here, too, her work seeks to transcend borders, including those imposed by language, as did the Zurich Dadaists, such as Tristan Tzara in his 1917 poem “Karawane.” Responding to the carnage of the nationalistic and imperialistic First World War, the Zurich Dadaists’ poetic outpourings attempted to replace stultifying national languages with an avant-garde Esperanto. According to Barsi, Shahroudi’s poems also “all have to do with war, war sounds and her condition as an emigrant who escaped from war and suppression, living now in a foreign country.”

By writing and reciting poems in more than one language, and, especially, employing sounds understood across borders, Shahroudi emphasizes language’s universal acoustic dimension.

By writing and reciting poems in more than one language, and, especially, employing sounds understood across borders, Shahroudi emphasizes language’s universal acoustic dimension — like the wind through the trees in the park that can speak to anyone, regardless of nationality or linguistic background, or the cymbals she clanged, the image of which recalls a famous photograph of Joseph Beuys in his May 1969 performance, “Iphigenie/Titus Andronicus.” Beuys’s performance was inspired by two violent, bloody plays rooted in antiquity: Goethe’s “Iphigenie in Taurus” and Shakespeare’s “Titus Andronicus.” Beuys, a Second World War veteran, transformed these narratives of revenge and murder into materials, sounds, and actions meant to suggest resurrection and redemption. Like Shahroudi, Beuys sought to transcend national borders, and to speak across languages, and even species, as when he explained pictures to a hare. Shahroudi’s performance in the “English Garden” extended this legacy into the present, performing not as a male war veteran, but as a woman war refugee, herself embodying and enacting border crossing.

Peter Chametzky is Professor of Art History at the School of Visual Art and Design at the University of South Carolina. He is the author of “Turks, Jews, and Other Germans in Contemporary Art,” from which this article is adapted.