Consent Isn’t Clear-Cut. Fanfiction Can Help.

Content note: This article discusses rape culture and rape apologism and includes some references to and descriptions of sexual violence.

American talk radio host Rush Limbaugh defends U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump for boasting about how he can “grab [women] by the pussy,” casting the idea of sexual consent as a strange, outlandish, immoral invention of “the left.” The father of Brock Turner, a college student convicted of three counts of felony sexual assault of an unconscious woman after a campus party and sentenced to six months in prison, bemoans the harsh sentence for what he calls “20 minutes of action.” A woman relives her sexual assault on national television in the hope of stopping her assailant’s confirmation to the United States Supreme Court. She fails. (And she is not the first to do so.)

This is rape culture. The #MeToo movement has brought the endemic nature of sexual violence into the public eye. In the United Kingdom alone, over 200 women are raped every single day. At the same time, those in power — from members of Parliament to judges to talk-show hosts — routinely dismiss rape allegations. Even in the most egregious cases, like that of Brock Turner, they find ways of blaming the victims and protecting the accused and guilty. And while feminist campaigners have been pushing against rape culture and for better education about consent, it is clear that sexual consent is — at best — a contested topic in contemporary Western societies and cultures.

Comments and cases such as these have gained public attention and prominence in the media partly because they are relatively clear-cut: Two men witnessed and stopped Brock Turner, and their testimony was crucial in securing his conviction. But focusing solely on these cases means we obscure experiences of sexual violence and consent violations that are less clear-cut: experiences that fall in a problematic liminal space, a gray area between “yes” and “no,” for a variety of reasons.

Although there is still plenty of work to be done in both research and activism with regard to the arguably less complex cases (i.e., those perceived as consent violations at the time they occurred), we desperately need a better understanding of the other ones: those cases in which the ways that we are taught to think about what “normal” sex is, about what constitutes a date or a romantic relationship, or about the kind of sex we have and what it says about us as people make it more difficult for us to meaningfully consent to sex. Think, for instance, of the young woman whose uncomfortable sexual experience with Aziz Ansari split opinions even inside the #MeToo movement.

Feminist academic approaches to sexual violence and consent are diverse and multidisciplinary with important contributions in fields such as psychology, feminist legal theory, and cultural studies. But even within feminist academia, consent in its own right is significantly undertheorized, and scholars struggle to account for the vast gray areas.

Even within feminist academia, consent in its own right is significantly undertheorized, and scholars struggle to account for the vast gray areas.

The psychologist Nicola Gavey argues that we, as a society, have a particular way of conceptualizing what “normal” (hetero) sex looks like. It is a combination of many, sometimes conflicting ideas, but it generally involves exactly one cisgender man and one cisgender woman; it starts with kissing and touching, progresses through undressing, and culminates in penile-vaginal intercourse, which ends when the man ejaculates. (You may recall this sounds remarkably like the script Aziz Ansari was following in his interaction with his date.) We also have dominant cultural ideas about what exactly requires consent, and when and how consent can be withheld or withdrawn. We even have an idea that all people experience sexual attraction and want to have sex, and that if someone doesn’t, something must be wrong with them. It is these dominant ideas that make it difficult to name such experiences as violations, and Gavey calls them the “cultural scaffolding of rape.”

There is, however, another community — not academic, not overtly activist — that has developed a word for this. Readers and writers of erotic fanfiction would call these scenarios “dubcon”: dubious consent.

Erotic Fanfiction and Consent

Dubcon takes its title from a tag on the fanfiction website Archive of Our Own (AO3): “slight dub-con but they both wanted it hardcore.” Tags on AO3 — an online archive owned and operated by fans that hosts over five million fanworks as of August 2019 — are pieces of metadata, intended to facilitate the organization and searchability of such fanworks. Yet their usage in the fanfiction community makes them so much more than that. And those eight words, “slight dub-con but they both wanted it hardcore,” perfectly encapsulate one of the remarkable things about this community, not only in its tags but also in large sections of its creative output and day-to-day interactions and practices: its nuanced engagement with issues of sexual consent, which I found in fanfiction circles long before I started researching it, that is at the same time delightfully playful and deadly serious.

Fanfiction is amateur-produced fiction based on existing, generally proprietary media such as TV shows, books, movies, and video games. Fans — mostly women and nonbinary people, and mostly members of gender, sexual, or romantic minorities — take the settings, plots, and characters from these “properties” and make them our own. We rewrite endings. We resurrect the dead. We give life to minor and marginalized characters. We imagine ourselves in the magical worlds we are passionate about. And in slash — the subgenre of fanfiction that focuses on same-gender relationships — we put queerness and sex back into texts they have been meticulously scrubbed out of. Of course Mr. Spock has been banging Captain Kirk, Cho Chang and Pansy Parkinson have been researching innovative uses for wands at Hogwarts, and Link, the pointy-eared protagonist of the Legend of Zelda video game franchise, is a trans woman! Have you not been paying attention? And considering that nearly 1.6 million of AO3’s five million fanworks are rated as mature or explicit, and that its community consists predominantly of women and nonbinary people, meaning that it is disproportionately affected by sexual violence, it would be more shocking if the community didn’t think about issues of sexual consent.

Fandom — the community of readers and writers of fanfiction — is where I first encountered the concept of “dubcon”: the idea that sometimes, for whatever reasons, consent is not clear-cut, not a matter of “yes” or “no.” I have been a part of this community for so long that I have no conscious memory of when I first came across the word. Fanlore, the fandom wiki, traces early usages of it to sometime in 2003, but fanfiction’s engagement with the gray areas of consent predates this usage by decades.

Wedged awkwardly between the academic books in my bookcase, there is a collection of slim, U.S. letter–sized, perfect-bound volumes older than me. Among them are Barbara Wenk’s “One Way Mirror” and Jean Lorrah’s “The Night of the Twin Moons.” In one of the origin stories of fanfiction I tell my undergraduate students, Lorrah and Wenk would be considered some of the foremothers of today’s fanfiction community. Decades before fandom found its way onto the internet, they wrote stories about the characters of Star Trek, typed them out, mimeographed them, had them bound into fanzines, and sold them at conventions or through the mail.

Wenk’s novel-length story explores, among other themes, material and social dependency within an intimate relationship. The first volume of Lorrah’s series focuses on the relationship between Spock’s parents, and particularly the emotional impact of pon farr, the Vulcan “fuck or die” mating drive. It is ultimately stories like these, where consent is a vast gray area between “yes” and “no,” mired in power relations and inequalities, that give us the most nuanced and productive engagements with questions of consent. It is those stories that are epitomized by those eight words: slight dub-con but they both wanted it hardcore.

Even though culture can reinforce many of the harmful ideas that contribute toward sexual violence and rape culture, it also has the potential to drive change.

The author who tags a story in this way draws a distinction between consent and the “wantedness” of sex. This is something that feminist researchers of consent from disciplines ranging from psychology to law have struggled with for decades. Sometimes, we may very much want to fuck someone silly, but other factors, such as the power imbalance between them and us, may impact whether we can genuinely and meaningfully give consent. Other times, we may feel little or no desire, and yet we may consent to sex for other reasons. Power still plays a role in these cases: Sex consented to for relationship maintenance when we are materially, financially, or socially dependent on our partner may still fall in the gray area of dubcon.

These are things I should perhaps have been given the opportunity to learn at school in sex and relationships education, or from my parents, or maybe even by cultural osmosis from media representations of sex and relationships. But I wasn’t, and ultimately I learned them from fanfiction, and from a handful of other feminist spaces I found myself in over the years. Was I alone in this? Did everyone else know these things already, and I had somehow missed them? Or were the discussions I was seeing in the fanfiction community around sexuality and consent part of a wider landscape of feminist activism, a space where women and nonbinary people got together to work these things out because no one had told us — maybe even because no one else knew to begin with?

The Potential of Fanfiction

Feminist scholars and activists see popular culture, including pornography and romance novels, as a key source of our dominant ideas about sex and consent. Popular culture is where we learn that pulling pigtails is a sign of affection, and that rejection is an invitation to keep making bigger and bigger romantic gestures. However, even though culture can reinforce many of the harmful ideas that contribute toward sexual violence and rape culture, it also has the potential to drive change. Audiences, after all, aren’t passive and don’t always read popular culture in exactly the same way; we bring our own ideas and experiences to it, and we interpret it and shape it as much as it shapes us. So, what do audiences do with media and culture that tell us that potentially coercive sexual situations are normal, romantic, or, in Nicola Gavey’s words, “just sex”?

Scholars of fandom and fanfiction have long seen fans as a particularly active type of audience. In his groundbreaking 1991 ethnography of fandom, Henry Jenkins calls them “textual poachers.” Fans, he argues, take bits of popular culture and repurpose them for their own ends. And those ends are generally subversive, counter to the dominant meanings and ideas of our society and the raw material we use. So, can such active audiences mount a meaningful resistance to dominant ideas of sex and consent? The fanfiction community consists predominantly of women and nonbinary people, a majority of whom identify as members of gender, sexual, or romantic minorities. This community produces a significant amount of work focused on sexual and romantic relationships, much of which is sexually explicit. As it turns out, at least parts of the fanfiction community are exactly the kind of active audience that critically engages with dominant ideas of sexuality and consent, that challenges those ideas and creates alternatives, and that is able to resist the idea that coerced, forced, or unwanted sex is normal or “just sex.” And there is a lot we can learn from them.

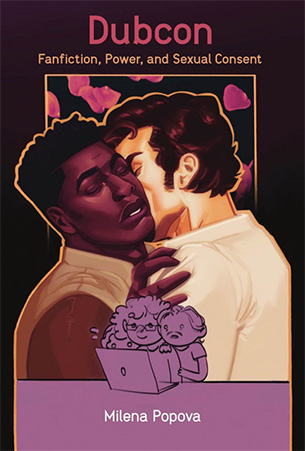

Milena Popova is an independent scholar, activist, and consultant working on culture and sexual consent, and the author of “Sexual Consent” and “Dubcon: Fanfiction, Power, and Sexual Consent,” from which this article is adapted.