Claire Fontaine: Foreigners Everywhere

“Far, far from you unfolds world history, the world history of your soul.”

–Franz Kafka

We always begin by wondering who are those who are not desired, only to later include them in the list of the undesirable. We ask them to spell out their names, because they are always foreign, unknown names. We ask them to get in line, stay calm, and not ask questions — there are no interpreters, anyway. We put them on file, we make long lists, we keep them in electronic memory, we let them sleep in the computers’ innards, then one fine day we wake them up: it is him, or her, or them that we don’t want anymore, that man, those children, and that woman, thanks, but we don’t want them.

It has happened before, it is still happening, the same procedure, the same feelings between the people carrying out orders and those being deported. Because “you can’t have a country reduced to the state of a strainer” (Dominique de Villepin, 12 May 2005), but, on the other hand, you have a fortress-like country, a door-code-like country, a deaf country, a killer-in-a-white-collar country, a politely-xenophobic country, a camp-like country. A country which expels, extradites and tortures (but discreetly); the country of police blunders and ill-digested colonialism, which one day drowned foreigners in the Seine, and on another imprisoned the “package carriers,”1 disguised as apron-flag harkis and pieds noirs [respectively Algerians who fought alongside the French army, and French settlers in North Africa, Trans.] devastated by the shame of having been born.

We will keep this country as it is, we work at it. We will actually spend 100 million euros next year to get rid of undesirables. Which is a fair price to pay. Why, anyway, did they come here in the first place, those people, far from their language, their family, and their country? But nobody ever asks them what their language is, or what their family is like, or what place they would like for themselves. Where are the undesirables going, when they disappear from sight? The terminology used says it all: into “retention” camps, they undergo an “expulsion,” fecal terms which fool no one; not only has capitalism failed to solve the problem of its waste, but the status of waste is rapidly overtaking what until yesterday wasn’t yet rubbish — this applies to things, this applies to people.

One aspect of the state of exception, which is normalcy for us, is that our compatibility with the system is the object of an ongoing negotiation which we endlessly work on, and that our usefulness on the labor market is a clockwork concept. They say “go home” to people who have lost their “home,” to such a degree that they decide to go to look for it at the other end of the world. We say “we don’t need you any more” to people who need the very work that rejects them. Foreigners are not people coming from somewhere else, people who belong to another “race.” The race of undesirables is simply the race of exploited people, those whom we relegate to the space of need, and who mistake the borders of their desires for the mirages of advertising. They reckon that they will disappear as such, that they are the outcome of unfavorable circumstances, of an unfinished democracy, that they are the symptoms of an infantile illness of global capitalism. But it isn’t true. They are the driving force of our economy, the immune carriers of wealth.

We will pay very dearly for our Western assertion of identity, our fear of proximity, our European communitarianism, and our opinions borrowed from newspapers and TV.

In any case you will say that this story is sad and well-known, but these things happen to Others, not to us, to Others; those Others whom we don’t ask who they are, and where they live. Our inner exile puts them in the first cell, locked up every day at the same time because of the general absence of time, and curiosity. Yet the others are here, nonetheless, in our place, this morning they’ve washed the windows of the local butcher’s shop, they were sitting on this same seat in the subway just before us, they were living in our apartment before they were evicted. Their pain infects the air we breathe, their toil, paid peanuts for, keeps our wages low, their isolation prevents them from organizing, their confinement silently materializes a prison aura around our lives. We will pay very dearly for our Western assertion of identity, our fear of proximity, our European communitarianism, and our opinions borrowed from newspapers and TV. We will know a poverty that will awaken the worst memories, a poverty that is not related to the economic crisis and recession, that is far more destructive, a poverty of possibilities which is already eroding all the borders of politics.

The state of the streets affects the state of our interiors. Since our apartments have become refuges where we cannot dare to host those who have been forgotten by police memory, our private property has been unmasked of its seeming innocence and is finally revealed as an act of war. We don’t want refugees here, because we are the real refugees, colonized by our own country which, for us, is just a country of adoption: a territory under the watch of global capital whose hostile laws we have to accept, or end up in the non-place of prison.

For some years now, we have been asked to be scared several times a day, and at times to be terrorized, and they dare talk to us about security. But security has never been a matter of militias, security can only be measured through the possibility of being protected when needed, it is the potential for friendship that lurks in every human being. Since it has been destroyed, everything in the public space is haunted by risk. Foreigners are everywhere, it is true, but we ourselves are strangers in our streets and in the subway corridors patrolled by men in uniform. These laws that reject strangers who have come from somewhere else cast a new light on Paris as a playground of Capital, on the “cleansing” of popular neighborhoods, and on the organization of inner tourism within the urban space. You will see what they mean when they install a “civilized space” or when they write on a notice that: “Your neighborhood is changing.” They mean that colonialism is war and that those being colonized are us, the rest of us.

…this text must end, it could go on, but there is no point. We know it. In order to exist it needs the poorest freedom that we still have: the freedom of expression, which is an irony. Language is already an ocean liner sinking under the weight of its inoffensiveness. It does not shelter us, it is always someone’s stranger. We urgently need to set off on another journey, that will put us on the side of the undesirable, questioning our personal boundaries, and ridding us of fear.

“We, on the other hand, with our sad experiences and fears, can’t help being frightened by every creak of the floorboards, without being able to help ourselves, and if one takes fright, the next one instantly takes fright too and even without knowing the proper reason for it.”

–Franz Kafka, Appendix, “The Castle“

—Claire Fontaine, 2005

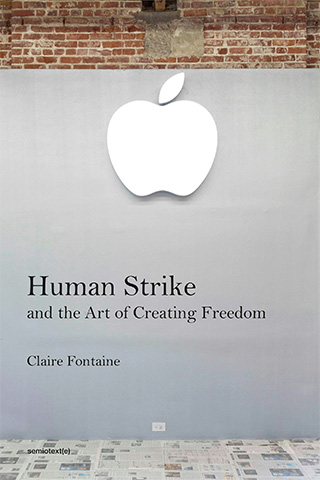

Claire Fontaine is a collective artist and the author of “Human Strike and the Art of Creating Freedom,” from which this essay is excerpted. “Human Strike and the Art of Creating Freedom” was published by Semiotext(e) in 2020.