Be Strong in the Broken Places: My Journey With Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s is a disease that can take 20 years or more to run its serpentine course. Experts say the pathology in the brain can begin when one is in their 40s, without noticeable symptoms. Disabusing the false stereotypes, no two patterns of Alzheimer’s are alike, and that confounds the researchers and acerbates the race for a cure. In short, one doesn’t get Alzheimer’s the day one is diagnosed, just as one doesn’t get cancer at the moment of diagnosis. It’s a journey in progress. A son or daughter who says their parent died of Alzheimer’s five or six years after a diagnosis, likely means that their mother or father was silently suffering from the progressing symptoms of Alzheimer’s for as long as two decades.

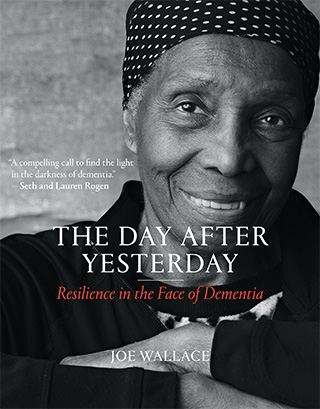

This essay is excerpted from Joe Wallace’s book “The Day after Yesterday: Resilience in the Face of Dementia,” a powerful collection of portraits and personal stories that humanizes the millions of people living with dementia. Click here to order the book.

I know firsthand of the stress. Alzheimer’s has devastated generations of my family tree. My maternal grandfather, my mother, and paternal uncle died of Alzheimer’s. And before my father’s death, he too was diagnosed with dementia. I was the family caregiver for my parents.

Now Alzheimer’s has come for me.

My mother, Virginia, was the hero of my life. She taught me how to live with Alzheimer’s and when asked, I promised her that I would write with candor and vulnerability to destigmatize Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. An articulate, brilliant, and beautiful woman, my mother taught me by her courageous example, in her fight with Alzheimer’s, that when the brain fails: write and speak from the heart, the place of the soul. As it was with my mother, my brain used to be my best friend, now there’s no chance for reconciliation. Has anyone ever asked you: “Tell me what’s in your heart, speak from it?” A poet writes from the heart, not the brain. And in Alzheimer’s, we all strive, as we can, to speak from our hearts.

I was diagnosed about nine years ago with Early Onset Alzheimer’s after experiencing the horrific symptoms of short-term memory loss, inability to recognize individuals and places that I’ve known all my life, difficulty completing simple tasks, terrible judgment, confusion with time and place, hallucinations, withdrawal, and challenges with problems. A battery of clinical tests, brain scans, and a SPECT scan confirmed the diagnosis. I also carry the Alzheimer’s marker gene APOE-4, which is on both sides of the family. The diagnosis came two weeks after I was diagnosed with prostate cancer, which, in consult with my doctors and family, I am not treating. It is my exit strategy.

Stephen King could not have designed a better plot for a sickness that slowly steals the mind, then pilfers the body, then robs your finances, pushing families, like mine, to bankruptcy.

Stephen King could not have designed a better plot for a sickness that slowly steals the mind, then pilfers the body, then robs your finances, pushing families, like mine, to bankruptcy. Then, there’s the depression that seems to have no bottom, and the flirts with suicide.

Yet Alzheimer’s can’t take your soul.

So please don’t be fooled by the inaccurate stereotypes of this disease. There are millions of individuals living with Alzheimer’s in the early stages, still highly functioning, perhaps not even diagnosed yet, who are fighting off horrific symptoms daily and beyond the observations of others. Our minds, in many ways, are like iPhones — still sophisticated devices, but with a short-term battery that pocket dials and gets lost easily.

Those on this journey aren’t stupid; we just have a disease that at times, often without notice, takes us down, dramatically diminishing, more and more, our ability to function. This is a disease that will devastate the Baby Boom Generation and generations to come, if something dramatic is not done to halt its assault.

I will never forget sitting in the neurologist office outside Boston, side by side, with my wife Mary Catherine, listening to the diagnosis. I felt as though I was slipping into Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland” where, “nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn’t.”

What “would be” was devastating. I felt the tears running down the sides of my face. My eyes didn’t blink. I reached for my wife’s hand, and asked: “What about the kids?”

Alzheimer’s IS about the kids: your kids, my kids, your grandchildren, my grandchildren. And we need to do something about it.

So where am I today? Sixty percent of my short-term memory, at times, can be gone in 30 seconds. More and more, I don’t recognize people I’ve known all my life; I experience penetrating, horrific hallucinations; fly into inexorable rage when the light in the brain goes out; I have a debilitating loss of filter, loss of self, incontinence, loss of judgment and time and place; also an intense at times numbing of the mind and body, and incredible withdrawal from friends and family. I also have little feeling in both my feet up to my knees and sustain blackouts with the right side of body collapsing without notice — neuropathy, complicated by brain signals that are not connecting properly. In addition, I have acute spinal stenosis and scoliosis, a condition accelerated by the breakdown of the body.

Then there’s the depression, the black hole that has no bottom, which often pushes one to the brink of a booster rocket to the planet Pluto.

Like Cancer and AIDS earlier, and Alzheimer’s today, depression is taboo — too messy, we can’t talk about it. Yet depression is as common in Alzheimer’s as forgetting a name. Alzheimer’s is not just memory loss, it’s a slow, yet complete breakdown.

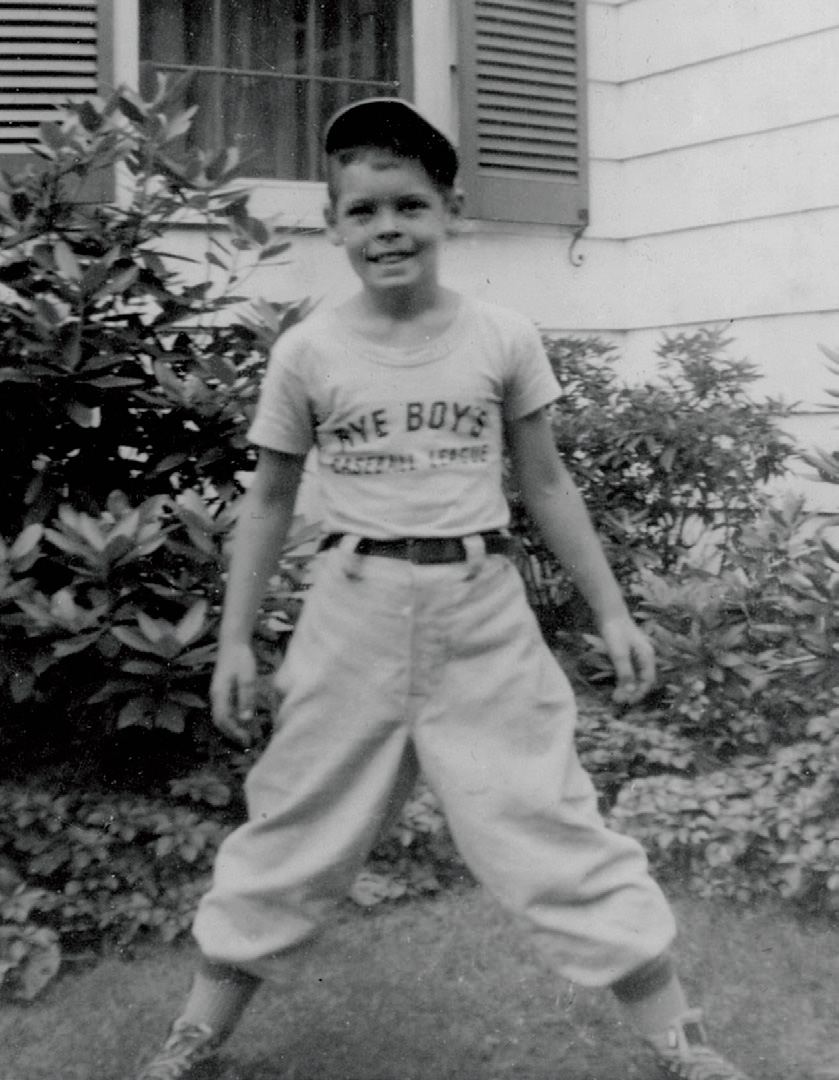

Years ago, I thought I was Clark Kent, Superman, an award-winning journalist who feared nothing. But today, I feel more like a baffled Jimmy Olsen. And on days of muddle, more like Mr. Magoo, the wispy cartoon character who couldn’t see straight, exacerbated by his stubbornness to acknowledge a problem.

The “right side” of my brain — the creative, sweet spot — is intact for the most part, although the writing and communication process now takes exponentially longer. The left side, the area of the brain reserved for executive functions, judgment, balance, continence, short-term memory, financial analysis, and recognition of friends and colleagues, is, at times, in a free fall.

Doctors advise that I will likely write and communicate with declining articulation, until the lights dim, but other functions will continue to ebb, as they are now. Daily exercise and writing are my succor to reboot and reduce confusion.

Daily medications, the legal limits, serve to slow down the progression of the disease and to help control the rage on a day when I hurl the phone across the room — a perfect strike to the sink — because in that moment I don’t remember how to dial, or when I smash the lawn sprinkler against an oak tree in the backyard because I don’t recall how it works, or, when in winter I push open the flaming hot, glass door to the family room wood stove barehanded to stoke the fire just because I thought it was a good idea, until the skin melts in a second-degree burn. Or, simply when I cry privately, the tears of a little boy, because I fear that I’m alone, nobody cares, and the innings are beginning to fade.

Alzheimer’s indeed is a sickness that runs in circles and eventually meanders in for the ultimate kill. It’s analogous to the prototypical arcade game Pac-Man in which a pie-faced yellow icon navigates a maze of challenges, eating Pac-dots to get to the next level. While the iconic video game was designed to have no ending, there are no “power pellets” in Alzheimer’s to consume the enemies of ghosts, goblins, and monsters, as my Pac-Man in slow motion consumes brain cells, one by one.

Game over!

Not always so, if one is willing to fight in faith, using gut instincts, and with the help of loving families and caregivers.

We learn legions from the words of others. The iconic poet Robert Frost once observed: “In three words I can sum up everything I’ve learned about life: It goes on.”

The only way to face this demon is head-on, through faith, hope, and humor, as this disease robs self-awareness, diminishes function. Empathy is the pathway to understanding and compassion and gives power and purpose to address this burgeoning health crisis.

In the last year, I’ve lost six close friends to the demon Alzheimer’s, now multiply that number around the world. Lots of spouses without mates, children without parents, grandchildren with fewer loved ones to hold them.

Perhaps Ernest Hemingway said it best when he observed, “The world breaks everyone, and afterward, some are strong at the broken places.” Be strong in the broken places . . .

A career journalist, Greg O’Brien is the author of the international award-winning “On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s.” He also serves on the Board of UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, in DC, is an advocate for the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund of Boston, and has served on the Alzheimer’s Association Early Onset Advisory Board in Chicago. This essay is excerpted from the book “The Day after Yesterday.”