At the Azraq Refugee Camp, Restoring Humanity Through Art and Design

The existential threats of climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the rising numbers of forcibly displaced people make visible a new reality of social, political, and economic inequalities that is impossible to ignore. As an increasing number of people are forced to move and adapt to unexpected life scenarios, they have to find strength, inspiration, and hope in moments and in places where it seems so easy to surrender to hopelessness.

Glimpses of our shared future may well be found in the present-day living situations of displaced people. Shouldered by hope, Syrians fleeing from conflict and crisis find their way across borders into processing centers and camps. Ninety kilometers from the Syria-Jordan border, a two-hour drive from the capital of Amman, almost 40,000 Syrian refugees found their shelter in the Azraq Refugee Camp. It is a centrally planned, closed camp built to address the basic needs of displaced Syrians. Deep in the Eastern Desert, the camp appears from a distance as an endless grid of white containers, bordered by an infinite fence, and surrounded by nothing but sand. The barren landscape extends to the horizon as evidence of these hostile living conditions, with temperatures reaching 118 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer.

Refugees at Azraq build imaginative collages of the homeland. They design familiar moments with objects of standardized humanitarian aid. It takes weeks to gather the necessary materials for a simple fountain, and when refugee construction is forbidden, it takes delicate knowledge of loopholes in the system to build the life-sized sandcastles resembling the Arch of Triumph in Palmyra. However tricky the process, to bring people together is a worthy cause. The Majlis, traditional living spaces, are at the core of the residents’ social lives and are the places where celebrations, casual visits, and gatherings happen around traditional coffee and tea rituals.

Fellowship is an important aspect of Syrian heritage, and older generations at the camp try to keep that tight-knit social structure alive.

Raised without a lived experience of Syria, the children of the camp form their identities from these symbols and social practices. Fellowship is an important aspect of Syrian heritage, and older generations at the camp try to keep that tight-knit social structure alive. Through acknowledging solidarity as a native characteristic for design at the camp, we are able to better highlight the making process as a conduit for heritage and cultural reproduction at Azraq.

The following images and texts are excerpted from “Design to Live,” a bilingual book in English and Arabic that documents designs by refugees through architectural drawings, illustrations, photographs, and texts by the camp residents, humanitarian workers, and researchers who collaborated on the book across cultural and disciplinary borders. (A PDF of the entire chapter, in both languages, can be downloaded here.) “Design to Live” is the product of a three-year joint project of the MIT Future Heritage Lab and the Syrian refugees at the Azraq Refugee Camp, supported by CARE-Jordan and the German Jordanian University. In its pages, we invite you to witness how art and design restore humanity within circumstances that deprive it. We invite you to experience the Azraq Refugee Camp not as a marginal moment of encampment, but rather a site full of life, of challenges and dreams that are individual, nuanced, and specific.

Designs

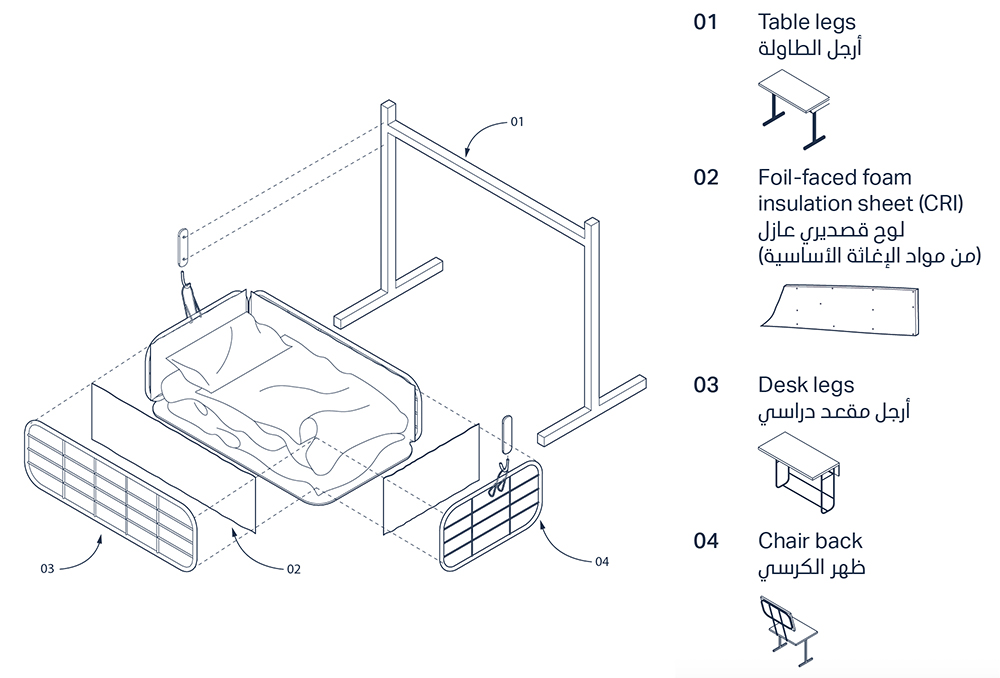

Rocking Crib

Ali Fawaz reappropriated old student desks into a rocking crib for his newborn. He reused the desk under-frame as a bearing structure and the stationary racks for the basket. He quilted the basket interior with layers of foil-faced insulation foam (CRI).

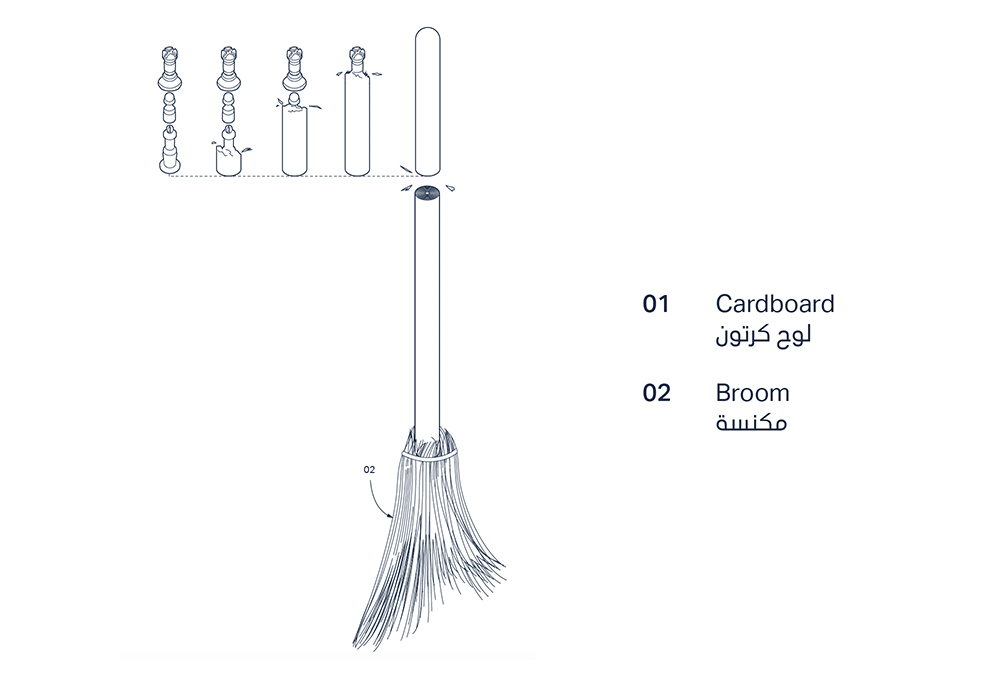

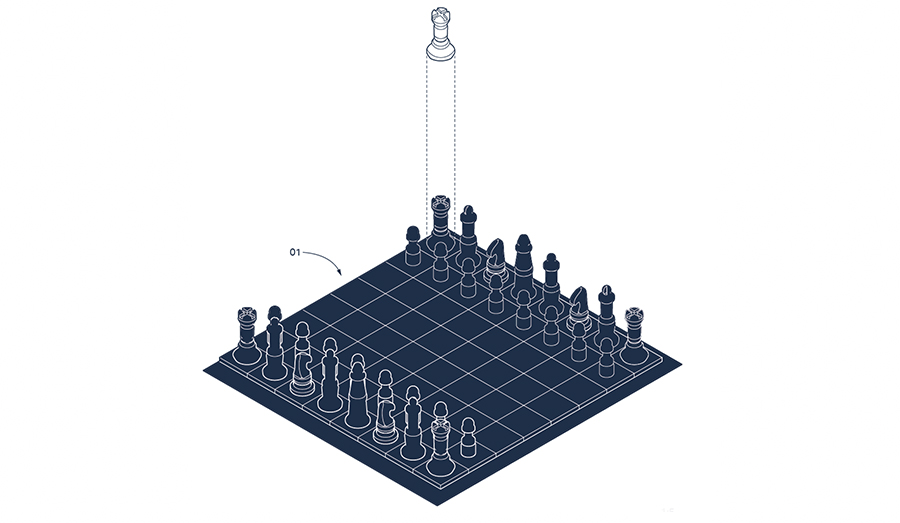

Chess Set

The wooden chess set is the result of laborious craftsmanship. The designer carved pieces from the length of a broomstick. The board is hand drawn on food packaging.

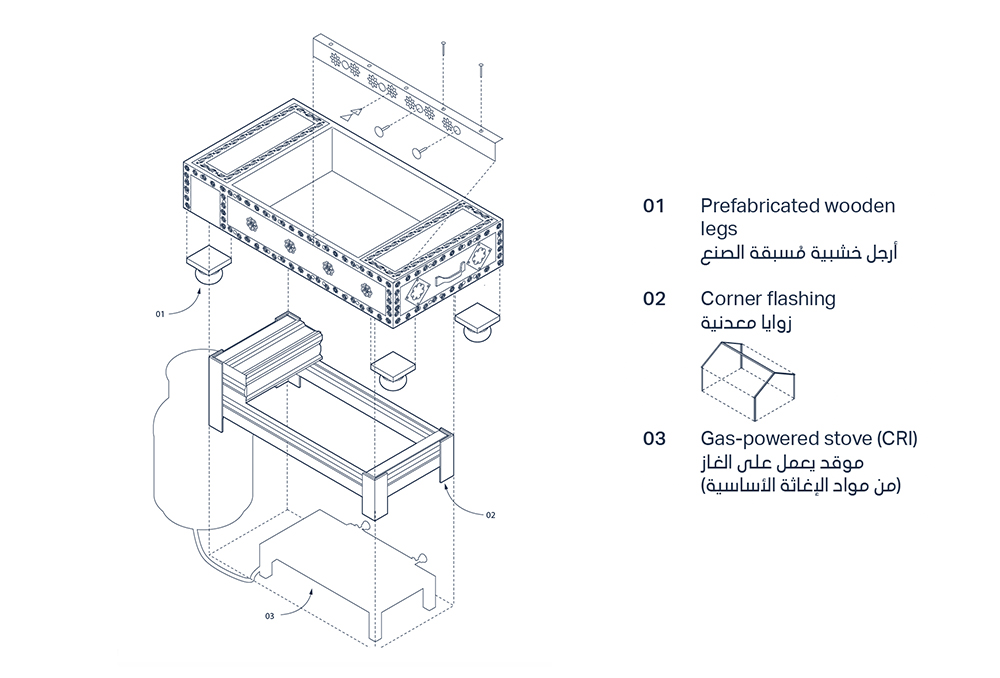

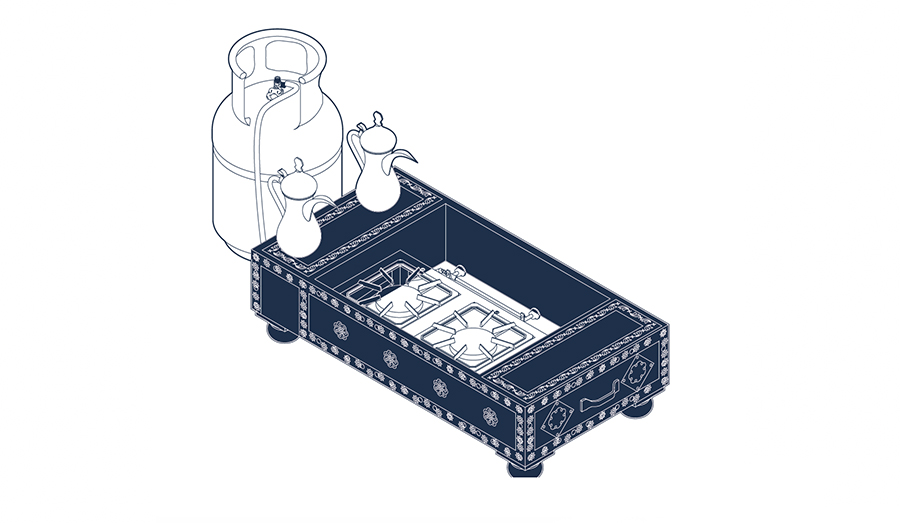

Coffee Station

Coffee and Tea are rituals of everyday life and a big part of the Majlis hospitality at the camp. The small appliance in this image is representative of a widespread design for the preparation of warm beverages. The device has two stoves, a raised platform for serving, hooks for the storage of the relevant utensils, and handles for portability. Abo Mohammad made the initial design with metal scraps and corner flashings from the T-Shelter. The second iteration is larger, wooden, and embellished with metal decorations he handcrafted himself.

Worldmakers

Majid Al-Kanaan (Abo Ali)

Abo Ali is the architect behind one of the most photographed structures at the camp, the clay arches in front of his house. The arches are now gone due to the lack of long-lasting building materials and the rough weather, but he recalls a time when his work was destroyed on purpose. “When I first made the structure, I was exploring what could be done with the sand and stone of this area,” he said, “but then one night I heard a huge bang and the entire household woke up to a man destroying my work.” The man had mistaken Abo Ali’s work for a religious shrine. “His brains were tired,” he says of the man, “so we let him go.”

Abo Ali was labelled a pagan for a while after the incident by several people, but he laughs it off: “I rebuilt the structure, but made it look like the Aleppo Citadel, and everyone flocked from every part of the camp to take pictures with it.” Abo Ali has an interesting nonchalance toward group dynamics, and interprets everything poetically. “Human beings are made of clay too. Allah took some clay and made us out of it, so we have an eternal empathy with the ground. Now there’s concrete. The world changed. Sobhan Allah.”

Ironically for his analogy, concrete is not allowed at the camp. “Brother, they don’t want us to stay here forever,” Abo Ali says. “And they know that if they give me concrete, I’ll build a three-story house for myself. I swear.” After all, most people living in Azraq are builders by trade and would do the same thing. But Abo Ali doesn’t want to stay here. He dreams of an “amazing” piece of land he owns back home in Syria, where he will recreate his designs the way he wants, without restrictions. “And I’ll make it last 100 years if I want to!”

Abo Mohammad Al-Homsi

Strong coffee. No Sugar. As the host of the Majlis, Abo Mohammad transfers the habits of Syrian life to the future generations currently living at the camp. He, himself, learned the rituals of coffee from his late father, who in turn learned the traditional ways of the Majlis from his own father. “The tools I used to prepare coffee in Syria were passed on for three generations. The copper pot is around 130 years old, and I took care of it to pass it on,” he says. Abo Mohammad had to leave his precious tools behind when he fled from war, but what he is still able to articulate is the essence of his heritage: hospitality and generosity.

Photo: Melina Philippou, April 2019.

As the eldest in the neighborhood, the gatherings take place at this house and the setup needs to always be ready for hosting. “It’s a symbol of Arab hospitality. Whenever anyone passes by, everything needs to be ready to entertain the company. And when my guests tell me they like my coffee pots and tools, I offer them as gifts.”

The Majlis is usually an informal affair, where people just walk in. It is a way to check on people. Who’s doing what, everyone’s health, families, and so on. In cases where invitations are sent for special occasions, Abo Mohammad insists that the first to be invited are the neighbors. Even before family members. “The close neighbor is better than the far blood relative,” he says. Even if, at the time of the invitation, he was not on good terms with his neighbors, he would find ways to resolve the dispute and host them.

Drawings: Noora Aljabi, Andrea Baena, Jaya Eyzaguirre.

Azra Aksamija, an artist and architectural historian, is Director and Founder of the MIT Future Heritage Lab (FHL) and Associate Professor in the MIT Department of Architecture and the Program in Art, Culture, and Technology.

Raafat Majzoub, an architect, artist, and writer, is Director of The Khan: The Arab Association for Prototyping Cultural Practices and Lecturer in the Architecture and Design Department of the American University of Beirut.

Melina Philippou, an architect and urbanist, is Program Director and Lead Researcher of the MIT Future Heritage Lab.

This article is adapted from their book “Design to Live.” A PDF of the entire chapter from which this article is excerpted can be downloaded here.