Should We or Shouldn’t We? Arguments for and Against Lockdown Drills

Leading school safety authorities, including the U.S. Department of Education, Safe Havens International, the “I Love U Guys” Foundation, the National Association of School Psychologists, and the National School Safety and Security Services, assert that emergency operations plans must be practiced with drills and exercises. Practicing allows school staff, students, and emergency responders to familiarize themselves with the procedures outlined in the plan so that they know what to do in the event of a threat or hazard, and to improve muscle memory. In fact, one of the major responsibilities of school and district safety teams is to engage in the planning and practice of drills.

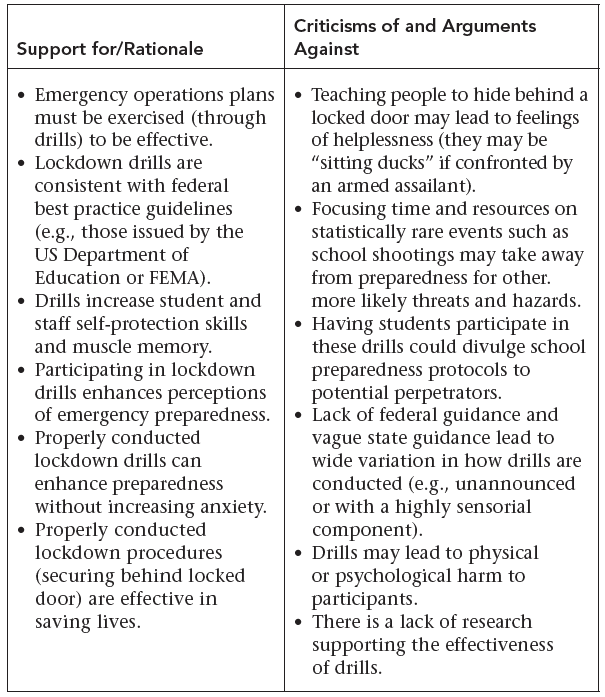

Despite these recommendations, lockdown drills (which are often erroneously equated with active shooter drills, options-based approaches, and full-scale exercises) have been at the center of attention and controversy in recent years. As with many contentious topics, people have assumed the role of either advocate or abolitionist when it comes to lockdown drills. In this chapter, we explore the commonly offered talking points as to why these practices should or should not take place. We also discuss the confusion between lockdown drills, options-based approaches, and highly sensorial exercises. The table below outlines the major arguments for and against conducting lockdown drills. Throughout the chapter, we provide evidence-based support and counterarguments to each point listed in the table in an effort to better understand the conversation around these practices.

Arguments for conducting lockdown drills

Related to the point made earlier that emergency operations plans must be rehearsed and applied, best practice guidance on emergency preparedness from the federal government specifies conducting lockdown (and other) drills. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), for example, published an extensive document on preparedness practices and evaluation in 2020, emphasizing how vital drills and exercises are in strengthening communities to engage in all aspects of emergency preparedness. Specific to schools, the U.S. Department of Education offers a pair of guides that include lockdowns as a specific, critical operational function (the relevant sections of the guides are referred to as functional annexes) for schools to include in their emergency operations plans. Both documents emphasize the importance of drills and exercises to ensure that school faculty and staff, students, parents, and community representatives understand their respective roles.

The Readiness and Emergency Management for Schools (REMS) Technical Assistance Center similarly includes drills and exercises as part of schools’ mitigation strategies. Mitigation is an aspect of preparedness that focuses on actions schools can take to reduce or eliminate death, injury, and property damage resulting from a crisis event; training and conducting drills can help keep the community safe and minimize these consequences. The Final Report of the U.S. Federal Commission on School Safety also indicates that each school’s plan should include multiple functions (with lockdowns included in the list) and hazards, and that the plan must be practiced so that students, teachers, and administrators know their roles and responsibilities. Therefore, conducting lockdown drills as part of comprehensive planning and preparedness efforts for multiple threats and hazards is a widely agreed-upon best practice.

Another argument for conducting lockdown drills is to teach students and staff necessary self-protection skills and increase perceptions of preparedness. Drawing from the larger field, one review indicated that 66 percent of studies of disaster education preparedness programs in which a variety of discussion-based and drill components were used with children showed positive outcomes, including increased knowledge and awareness of disaster response and improved attitudes toward preparedness. As applied to earthquake preparedness, the combination of lectures — providing information about this natural disaster and how to respond — and drills — offering a brief overview of behavioral steps and then practicing them — resulted in the highest knowledge scores among a sample of upper elementary school students in Israel. Several studies focusing on lockdown drills specifically have demonstrated that children’s participation in lockdown drills can increase their skill in implementing the lockdown procedures. Collectively, the findings indicate that children improve their knowledge and skill mastery after participating in training and lockdown drills.

Collectively, the findings of several studies indicate that children improve their knowledge and skill mastery after participating in training and lockdown drills.

It is important that people not only know what to do but also perceive themselves to be prepared. According to protection motivation theory, people are motivated to take action to safeguard themselves against harm based on the weighing of vulnerability, risk (e.g., the likelihood of a threat’s occurrence), and potential consequences (e.g., severity) against the perceived benefits of engaging in protective behavior, their self-efficacy (the belief that one has the ability to take the actions needed to protect oneself), and response efficacy (whether the actions will be effective in reducing or eliminating the threat). Therefore, a goal of teaching and practicing emergency preparedness procedures such as lockdowns is to increase beliefs or perceptions about being prepared to engage in protective actions. In our large-scale study of lockdown drills in an urban school district, we found that participation in training and drills led to increased perceptions of preparedness on the part of both students and educators.

In teaching and practicing these skills and increasing preparedness, it is important not to create undue anxiety or arouse fears on the part of participants for their own safety. Although protection motivation theory suggests that experiencing a sense of vulnerability and risk actually motivates people to engage in protective behavior, it is undesirable to create situations that cause students or staff to experience undue anxiety and stress or to feel unsafe in schools. Highly sensorial simulations and full-scale exercises are much more likely to elicit these responses. In contrast, research has found that when drills are conducted in accordance with best practices, anxiety typically remains unchanged or is even lowered, suggesting that the lockdown drills are not contributing to consistent, problematic anxiety and fears for student participants.

Beyond skill mastery and their contribution to perceptions of preparedness, perhaps the most compelling argument for conducting lockdown drills is to save lives. Similar to evacuating to escape from a fire or wearing a seat belt to protect from injury or death in a car accident, securing behind a locked door has been identified as the most effective way to prevent injury or death during an active shooter situation. According to testimony provided to the Sandy Hook Advisory Commission, no one has been injured or killed behind a locked door because the lock failed. If people have participated in lockdown drills and practiced locking the door and getting out of sight, their improved muscle memory can make this a more automated response, which may be vital in taking the steps necessary to prevent injury or death.

Arguments against conducting lockdown drills

One of the criticisms of lockdown drills is that teaching students and staff to hide behind locked doors may make them “sitting ducks,” a term often used in news reports that discuss bringing options-based training to schools. The concern is that hiding will make people vulnerable and more at risk of being killed or injured if faced with an armed assailant such as an active shooter. Therefore, options-based or multi-option approaches such as A.L.I.C.E. (which stands for alert, lockdown, inform, counter, evacuate), Run Hide Fight, or Avoid Deny Defend are being used increasingly to empower people with a survival mindset and to train individuals to use a variety of options, including running or fleeing the scene and barricading doors, actively resisting or fighting an armed assailant resorted to only when no other good options exist. A further argument for options-based approaches is that law enforcement personnel have used distraction techniques successfully to stop an incident and save lives. Indeed, the actions of evacuation, hiding, or acting against the assailant are part of the prevailing response to an active shooter designed by DHS for use in workplace settings. Since the Sandy Hook shooting, it also has been applied to K–12 schools.

Only a few studies have been conducted on options-based approaches. In an experimental study of a simulated shooting with adult participants in an A.L.I.C.E training session, the options-based approach simulation was completed in a shorter period of time and fewer people were “shot” with airsoft guns, which the authors suggested indicated greater survivability. A separate study of video and audio simulations with school staff members, however, found that those who had completed options-based training performed worse than those who had not been trained. Specifically, they misjudged almost twice as many critical action steps, such as attacking anyone depicted as having a gun, regardless of the scenario, or choosing to evacuate even if doing so would increase danger. The scant research available therefore is inconclusive and does not address the involvement of children in these approaches. One exception is a study of fourth through twelfth graders who participated in discussion-based lessons on the A.L.I.C.E. protocol. The researchers found that most students (over 85 percent) felt more prepared and less scared or expressed no changes in such perceptions after learning the options. The students who felt more scared also were likely to be fearful of other preparedness procedures, such as tornado drills and stranger danger drills. More research is needed to examine the effectiveness and impact of multi-option approaches, particularly when students are participating and a drill component is involved.

Although the previous criticisms, such as not teaching people in the options-based approaches, are specific to lockdown drills, most of the other arguments are about active shooter or armed assailant drills, which often encompass lockdowns. Lockdowns differ from simulations and options-based approaches, and the National Association of School Psychologists, National Association of Resource Officers, and Safe and Sound Schools have called for accuracy in differentiating between these drills and exercises. Since lockdowns often are incorrectly lumped together with active shooter drills, it is important to address these criticisms.

One report indicated that A.L.I.C.E. training cost a school district $56,000 in one year, plus $25,000 in each of the next two years.

Another related concern raised about lockdown drills when the focus is on armed assailants is that allocating time and resources to statistically rare events such as school shootings may divert resources from other, more comprehensive school safety planning and preparedness efforts for multiple hazards. The joint statement from Everytown for Gun Safety, the American Federation of Teachers, and the National Education Association, for example, raises the issue that for-profit companies charge tens of thousands of dollars to provide active shooter training when the funds could be spent on preventive approaches such as threat assessment, employing more school-based mental health professionals, upgrading security, and improving the school climate. One report indicated that a school district in California paid more than $32,000 over three years for A.L.I.C.E. training. Another indicated that the training cost a school district $56,000 in one year, plus $25,000 in each of the next two years. In contrast, some programs, such as the Standard Response Protocol, provide online training resources for lockdowns and other response protocols to K–12 schools at no cost.

Critics of lockdown drills also suggest that involving students may be problematic because it may divulge school preparedness protocols to potential perpetrators of school shootings. This argument does not take into account that locking a door creates a time barrier, which will be an obstacle whether or not a perpetrator knows that this is part of the protocol. In addition, the reality is that only a minuscule percentage of students might go on to engage in an act of massive violence against the school; the far greater likelihood is that teaching thousands of students to protect themselves outweighs the chance that training in these emergency protocols would give potential perpetrators information they otherwise would not know.

A criticism with clear policy implications is the very wide variability in the ways in which schools practice drills. There is no federal standard relevant to these practices, and statutes concerning drills often are vague; thus practices vary dramatically from school to school. Multiple media reports exist of drills that included gunshots to make the experience more real or of schools telling teachers there was an active shooter when it only was a drill. There also are reports on the use of stage blood and fake guns as police pose as active shooters (with student volunteers playing the role of victims).

Conducting drills that simulate the actual experience of being threatened by a shooter (e.g., with actors, gunshots, and stage blood) has raised concern about the potential psychological and physical harm that may ensue. Empirical research on this topic is very limited, and although the evidence on lockdown drills to date does not support the contention that carefully conducted drills elicit stress and fear, studies have not been conducted on the more sensorial approaches that are more likely to be traumatizing. In options-based approaches that teach students and staff to directly confront an assailant, there is added concern about increased harm and more deaths. These fears about the possible effects of these practices have led to calls to end active shooter drills (and, by extension, lockdown drills). Professional organizations, however, including the National Association of School Psychologists, the National Association of School Resource Officers, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, rather than opposing all drills, have provided best practice guidance on conducting drills and have advocated for including this guidance in legislation.

The evidence on lockdown drills to date does not support the contention that carefully conducted drills elicit stress and fear.

Finally, critics point to an alarming lack of research on the practice of drills, even though they are conducted routinely in schools every day across the country. The American Academy of Pediatrics has advocated for funding to research the effectiveness, goals, and potential unintended consequences of drills. Although several recent studies have begun to examine these practices, because of the great variability in implementation across schools, several specific components have not been carefully evaluated. When it comes to the safety of children at school, it is clear that schools, families, and the general public do not want to wait for tragedy to strike and instead demand action. At the same time, there is understandable concern that the rush to do something already has done, and could potentially do more, harm than good if drills are not implemented carefully and according to best practices.

Finding common ground

Implementing practices that increase preparedness while not causing harm is critical to reach the ultimate and common goal of saving lives. There are impassioned arguments on both sides of the issue as to whether or not lockdown drills should be conducted with students. The arguments against lockdown drills listed in the table and discussed in this chapter include the suggestion that such practices teach people to be helpless behind locked doors, misallocate resources toward statistically rare events, divulge school protocols to potential perpetrators, lack clear-cut federal and state guidance, increase the potential for physical or psychological harm, and lack research support. Arguments in favor of conducting lockdown drills with students include increasing self-protection skills and perceptions of emergency preparedness without increasing anxiety, improving effectiveness in saving lives, and following federal guidance and best practices regarding the need to practice emergency operations plans for them to be effective. The tremendous variability in the implementation of drills and confusion over the terminology, resulting in the conflation of different practices — active shooter drills might consist of a lockdown, at one end of the spectrum, or, at the other end, a highly sensorial simulation during which people are empowered to flee the area, take cover and hide, or throw objects and use physical force in an attempt to stop the perpetrator — add fuel to the controversy. One thing that most agree on is that schools are using variations of drills routinely — often, but not always, by state mandate — and that research has lagged behind.

Jaclyn Schildkraut is Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at SUNY Oswego. Amanda B. Nickerson is Professor of School Psychology and Director of the Alberti Center for Bullying Abuse Prevention at the University at Buffalo SUNY. Schildkraut and Nickerson are the authors of “Lockdown Drills,” from which this article is excerpted.