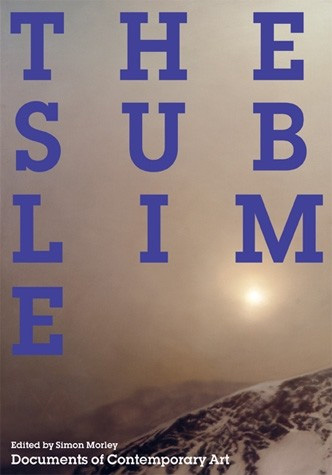

A Short History of the Sublime

Author’s note: Today we are constantly learning of new realities too vertiginously complex, it seems, for us ever fully to encompass them in our mind. Astronomers now believe, for example, that the visible universe contains an estimated 100 billion galaxies and that each galaxy also consists of billions of stars emitting rays in myriad variations of color from glimmering cool reds to radiant hot blues and whites. “Wow” often tends to be our initial lost-for-words response to such intimations of otherness or infinity. Under the aegis of the sublime — a concept in evolution since the classical era — “The Sublime,” the anthology from which the following article is excerpted, explores the range of recent artistic theory and practice that attempts to articulate such moments of mute encounter with all that exceeds our comprehension. It investigates, via the writings of contemporary artists as diverse as Anish Kapoor, Mike Kelley, Doris Salcedo, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Fred Tomaselli, and Marina Abramovic, what a contemporary sublime might be and what it might mean in today’s world. Culled from the introduction to the volume and featured below is a brief history of the sublime, from the classical era to our own.

The word “sublime” may seem rather outmoded — etymologically it comes from the Latin sublimis (elevated; lofty; sublime) derived from the preposition sub, here meaning “up to,” and, some sources state, limen, the threshold, surround or lintel of a doorway, while others refer to limes, a boundary or limit. In the Middle Ages sublimis was modified into a verb, sublimare (to elevate), commonly used by alchemists to describe the purifying process by which substances turn into a gas on being subjected to heat, then cool and become a newly transformed solid. Modern chemistry still refers to the “sublimation” of substances but of course without its mystical alchemical connotation, whereby purification also entailed transmutation into a higher state of spiritual existence.

“Sublime” begins to acquire its modern resonances in the 17th century when it appears in the translation of a fragmentary Greek text on rhetoric by the anonymous Roman-era author known as Longinus. The first translation of this work, Du Sublime (1674), by Nicolas Boileau, signaled a new interest in the investigation of powerful emotional effects in art. Longinus had declared that true nobility in art and life was to be discovered through a confrontation with the threatening and unknown, and drew attention to anything in art that challenges our capacity to understand and fills us with wonder. The sublime artist was, according to Longinus, a kind of superhuman figure capable of rising above arduous and ominous events and experiences in order to produce a nobler and more refined style.

From the mid 18th century, however, the word began to be used in a different context that reflected a new cultural awareness of the profoundly limited nature of the self, and which led artists, writers, composers and philosophers to draw attention to intense experiences which lay beyond conscious control and threatened individual autonomy. Closely associated with the Romantic movement, the concept of the sublime began to be employed by those who wished to challenge traditional systems of thought that were couched in the old language of religion, a rhetoric that now seemed founded on outdated conceptions of human experience. They hoped, as the contemporary philosopher Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe has characterized it, to explore “the incommensurability of the sensible with the metaphysical (the Idea, God).”

In “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful” (1757) the Irish political theorist and philosopher Edmund Burke noted that there were certain experiences which supply a kind of thrill or shudder of perverse pleasure, mixing fear and delight. He shifted the emphasis in discussions of the sublime towards experiences provoked by aspects of nature which due to their vastness or obscurity could not be considered beautiful, and indeed were likely to fill us with a degree of horror:

The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully is Astonishment, and astonishment is that state of the soul in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror … No passion so effectually robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear. For fear, being an apprehension of pain or death, operates in a manner that resembles actual pain. Whatever therefore is terrible, with regard to sight, is sublime too … Indeed terror is in all cases whatsoever, either more openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.

Burke was interested in what happens to the self when assailed by that which seems to endanger its survival. He also moved the analysis away from the sublime object and towards the experience of the beholder, thus making his enquiry a psychological one. The sublime, declared Burke, was “the strongest passion,” and he belittled the importance of the beautiful, claiming that it was merely an instance of prettiness. The sublime experience, on the other hand, had the power to transform the self, and Burke, like Longinus, saw something ennobling in this terror-tinged thrill, as if the challenge posed by some threat served to strengthen the self.

The sublime, declared Burke, was “the strongest passion,” and he belittled the importance of the beautiful, claiming that it was merely an instance of prettiness.

Immanuel Kant, in his “Critique of Judgement” (1790), also set out to explore what happens at the borderline where reason finds its limits. He characterized three types of sublimity — the awful, the lofty, and the splendid — and continued and deepened the shift of focus initiated by Burke, by asserting that the sublime was not so much a formal quality of some natural phenomenon as a subjective conception: something that happens in the mind. He thereby shifted the analysis towards the impact and consequence of the sublime experience upon consciousness, and argued that the sublime was essentially about a negative experience of limits. It was a way of talking about what happens when we are faced with something we do not have the capacity to understand or control – something excessive.

Behind Kant’s discussion lay a keen sense of the independence of nature, whose sheer complexity and grandeur continuously exceeds any human ability to control or understand it. This sense of the sublime may be initiated by the terrifying aspects of nature such as Burke describes, or be provoked by an experience so complex that our inability to form a clear mental conception of it leads to a sense of the inadequacy of our imagination and of the vast gulf between that experience and the thoughts we have about it. We are made aware, Kant observed, that sometimes we cannot present to ourselves an account of an experience that is in any way coherent. We cannot encompass it by thinking, and so it remains indiscernible or unnameable, undecidable, indeterminate and unpresentable.

“The feeling of the sublime,” wrote Kant, “is at once a feeling of displeasure, arising from the inadequacy of imagination in the aesthetic estimation of magnitude to attain to its estimation of reason, and a simultaneous awakened pleasure, arising from this very judgement of the inadequacy of sense of being in accord with ideas of reason, so far as the effort to attain to these is for us a law.” Thus because the sublime addresses what cannot be commanded or controlled, it is grounded in an awareness of lack. And as a consequence of this awareness of an inaccessible form of excess, argued Kant, we come to a recognition of our limitations, and so transform a sense of negative insufficiency into a positive gain: Such experiences serve to establish our reasoning powers more firmly within their rightful, although diminished, domain.

Several other important 19th- and early 20th-century thinkers also contributed to the evolution of modern concepts of the sublime. Friedrich Schiller claimed in “On the Sublime”(1801) that while the beautiful is valuable only with reference to the human being, the sublime is the way the “daemon” within man reveals itself. Friedrich Hegel, in his “Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion” (1827) also contested Kant’s essentially negative interpretation. He saw the sublime not so much as a voiding of the power of reason but as a moment of fusion with the Absolute in which the beautiful is fulfilled, and declared that sublimity was the way by which the divine manifested itself in the natural world. In a similar vein, Arthur Schopenhauer, in “The World as Will and Representation” (1819), explored the fissure that lies at the heart of being, and envisaged a self that can in certain situations observe itself in the very act of confronting a fearful inner abyss, and by so doing attain a certain dark grandeur.

Friedrich Nietzsche extended these arguments to a point where he urged the abandonment of reason altogether. In “The Birth of Tragedy”(1872) he cast the truly sublime individual as someone willing to abandon the safe dream of “Apollonian” rationality, where all is light and sanity, in order to embrace instead “Dionysian” intoxication — the frenzy of the God of wine and madness.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Sigmund Freud deepened these varied perspectives in two important ways, although without directly addressing the philosophical context. In his concept of “sublimation” Freud argued that in order to find psychic stability the “normal” ego necessarily bases itself upon the suppression of undesirable urges and traumatic memories, and these are transformed into “purer” and more morally and socially acceptable forms. Freud also identified the continuing encounters of the ego with such destabilizing, only partially repressed, psychological forces as generating what he called the “uncanny,” which he characterized as a feeling of unsettling ambivalence, a kind of fear originating in what is known of old and long familiar things.

Indeed, to many thinkers of the early and mid 20th century the conditions of daily life within modern technological society could seem one continuous and disturbing experience, causing what the German writer Walter Benjamin termed a disorienting psychic condition of traumatic “shock,” with hugely destabilizing consequences not only for the individual but also for society.

Meanwhile, from his different psychoanalytical perspective Carl Jung explored through his study of mystical and alchemical texts the connotations of sublimity in its earlier sense. From the procedures of such proto-scientific works he drew analogies with the progress of the psyche towards greater self-awareness, or as he termed it, “individuation.” The dissident surrealist Georges Bataille also sought a way to express in modern terms the experiences described in traditional mystical texts. Drawing on Nietzsche, he declared that in such documents we witness the recording of moments when the self is forced to “remain in intolerable non-knowledge, which has no other way out than ecstasy.”

Simon Morley is an artist and Assistant Professor at Dankook University, South Korea, in the School of Fine Art. He is the editor of “The Sublime,” from which this article is excerpted. His book “The Simple Truth: The Monochrome in Modern Art” was recently published by Reaktion Books.