A Guide to the Gravesites of Architects

All working architects leave behind a string of monuments to themselves in the form of buildings they have designed. But what about the final spaces that architects themselves occupy? One might expect to find imposing or self-congratulatory memorials, yet most architects’ gravesites are rather understated. Featured below is a selection of photographs and notes on a dozen of the sites Henry Kuehn researched for his book “Architects’ Gravesites: A Serendipitous Guide,” as well as the author’s preface.

My interest in this project probably goes all the way back to a course in architectural history that I took from the renowned Vincent Scully. Despite having a career in business, I was profoundly influenced by the Scully course, which led me to several architecture-related endeavors during the ensuing years. These included affiliations with the Society of Architectural Historians, the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, the Architecture and Design Committee of the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Chicago Architecture Foundation. It was as a director of the Graceland Cemetery tour of the Chicago Architecture Foundation that I came to realize that Graceland is the final resting place for a significant number of prominent American architects.

Thus began my task of researching, visiting, and photographing sites across the country. In this quest I identified over 200 architects of interest and located the gravesites for most of these.

As I dug into this project, the fundamental question that arose was: how have the men and women who designed the country’s most important and impactful architecture been remembered? Architects from the beginning of civilization have created incredible monuments — the Great Pyramids of Giza and the Parthenon come to mind. In America, architects have created impactful monuments such as the Lincoln Memorial and the St. Louis Arch. Having the interest in and capability of designing such lasting edifices, it seemed logical that these important architects would have put some thought and effort into how they themselves would be remembered.

I was surprised by the results. Certainly a few of the architects I investigated have the imposing and self-congratulatory memorials that I had imagined would exist. However, very few have monuments that in any way depict the architectural style for which the architect is noted. Instead, many are situated inconspicuously in lovely, serene, and out-of-the-way settings. The cremated remains of some of these great designers reside in highly unlikely places — the closet of a daughter, or the attic of a house once designed and lived in by the architect. For most of these architects the monuments are quite simple and understated — often just a headstone noting simply their names and dates and, occasionally, that this person had been an architect. It seems strange that these great architects, who created landmark structures during their lives, put so little thought into how they would be memorialized for time eternal. Apparently most of these architectural giants, like most of us ordinary people, either did not feel like dealing with death or felt that a lasting memorial for them was not important. What sets this group apart, perhaps, is that, in a striking number of cases, they chose not to have a marker at all but instead directed that their ashes be scattered at a place of special importance to them.

One can only hope that current and future architects will be inspired by their peers and, thereby, revive the diverse art of grave marker design. If this opportunity is ignored, the final places of today’s important architects will go largely unnoticed by future generations.

The cremated remains of some of these great designers reside in highly unlikely places — the closet of a daughter, or the attic of a house once designed and lived in by the architect.

When it came time to put pen to paper I needed to establish ground rules for this effort. Since tomes have been written about most of these architects, and ample information about their works and careers can be found elsewhere, I have chosen not to provide lengthy biographical information. Rather, I concentrate on their gravesites and share the information I have found regarding how their monuments came to be.

Deciding who among all the architects of the world is notable and American was a challenge that required setting some limits. As a result there are probably a number of architects and designers who the reader feels should have been included but were not. I have included a number of architects who are not American but did significant work and were highly influential in this country — and, I might add, they have some wonderful graves! I also have included some landscape designers who worked closely with major architects on significant projects. Finally, I have included several engineers who are responsible for designing structures that have had enormous impact on our country.

It is no surprise that the highest honor that the American Institute of Architects awards in its field, the AIA Gold Medal, has been bestowed upon 42 of the architects included in this project. What is interesting is that many were given the awards long after their death, meaning that their influence had not been realized until many years after they had passed.

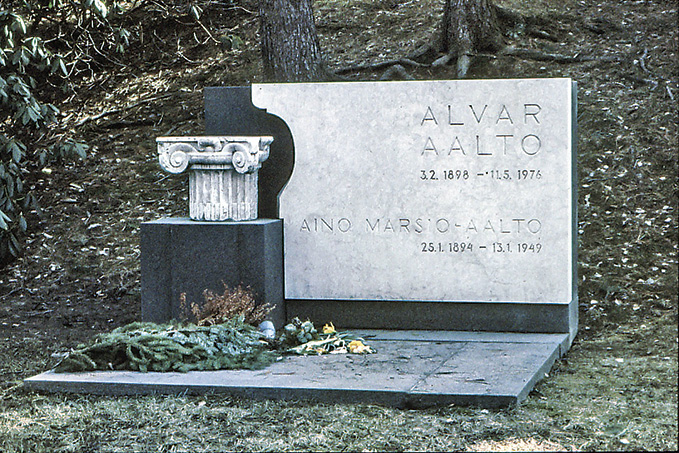

Alvar Aalto (1898-1976)

Hietaniemi Cemetery, Helsinki, Finland

It may seem strange to begin the list of architects with one who is not generally considered an American architect. However, Aalto designed two buildings in America that received much attention. His acclaimed Finnish Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair led to a professorship for him at MIT. While there he designed the much-admired Baker House, a large serpentine dormitory that overlooks the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Ironically, the namesake of this building, Dean Everett Moore Baker, died in the same plane crash in Egypt that took the life of architect Matthew Nowicki, who will be discussed later. His second wife, Elissa, also an architect, designed Aalto’s grave marker.

Raimund Abraham (1933–2010)

Mazunte, Mexico

Though Abraham was born and trained in Austria, he had significant impact on the American architectural community by his being part of the visionary faculty created by John Hejduk at Cooper Union in New York City. His enigmatic, poetic drawings, several about a visionary “house,” were a major influence on a generation of students. Yet he was also a practical builder. His best-known work is the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York City, which received high praise from critic Kenneth Frampton.

Abraham is buried near the home he designed for himself in Mazunte, Mexico. His grave marker is a “house” of bricks built by his friend and neighbor, Checo Diaz. His ashes are in an urn buried beneath the marker. The flower urn atop the marker was purchased years earlier by Abraham and his daughter.

Edmund Bacon (1910–2005)

Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

After studying architecture at Cornell University, Bacon continued on at the Cranbrook Academy with Eliel Saarinen. From there he returned to his native Philadelphia, where he eventually became director of the city planning commission and had a major role in implementing a new city master plan.

Bacon was cremated and his ashes were scattered on the grounds of a favorite family retreat built by his mother in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania.

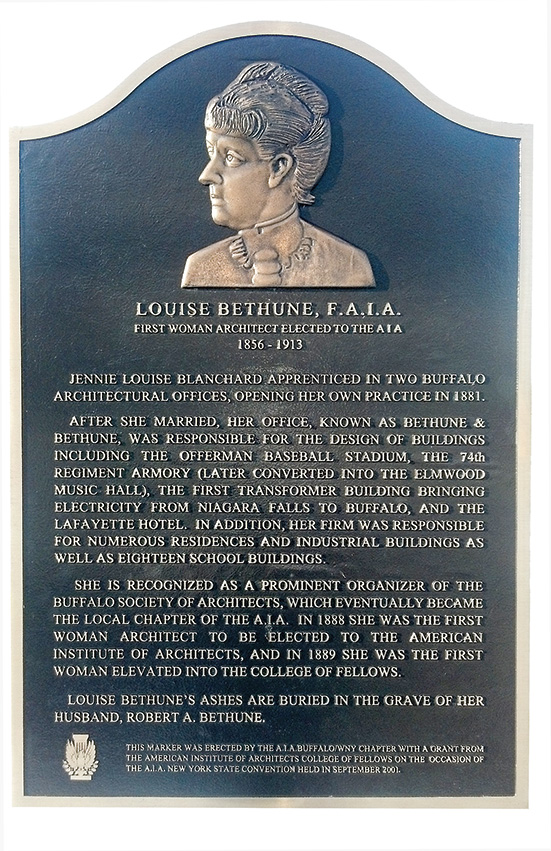

Louise Bethune (1856–1913)

Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo, New York

After apprenticing with other architects, Bethune and her husband opened an architectural office in 1881. By so doing, she is credited with being the country’s first professional woman architect. Despite her importance, she is buried next to her husband beneath a headstone bearing only his name. Acknowledging this oversight, the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects arranged for the installation of a nearby plaque that proclaims her accomplishments and significance.

Marcel Breuer (1902–1981)

Wellfleet, Massachusetts

Part of the Bauhaus movement in Germany, Breuer immigrated to the United States and maintained an ongoing relationship with Walter Gropius. He established what became a significant architectural practice, designing residences, churches, schools, and office buildings.

Breuer’s cremated remains are buried beneath a block of granite on the property of the residence he designed for himself. The markings on the stone are hard to decipher but apparently were chosen by the self-deprecating Breuer to say, “Here lies Breuer who broke his knee entirely of his own stupidity.”

Charles Eames (1909–1978) and Ray Eames (1912–1988)

Calvary Cemetery, St. Louis, Missouri

Charles and Ray Eames were a husband and wife team who met at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. While there the Eameses were exposed to the influence of the school’s founder, Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, and can be seen in many of their designs. They also became life-long friends with Eliel Saarinen’s son, Eero. Later, Eero Saarinen said that Charles Eames, along with his father and Matthew Nowicki, were the biggest influences in his life.

The Eameses worked together for virtually their entire careers, designing buildings as well as many well-known pieces of furniture. Their cremated remains bear no markers and reside quietly and anonymously within the Eames family plot.

Harvey Ellis (1852–1904)

St. Agnes Cemetery, Syracuse, New York

Ellis was an enigmatic architect and artist who worked for such luminaries as H. H. Richardson, Leroy Buffington, Gustav Stickley, and possibly Louis Sullivan. Many believe that some of the works of these giants were actually the creations of Ellis. However, his abuse of alcohol and elusive personality prevented him from ever receiving proper credit for his many sizeable contributions.

Much as he was overlooked in life, his gravesite was neglected for many years until a group of his admirers arranged to have the current marker installed.

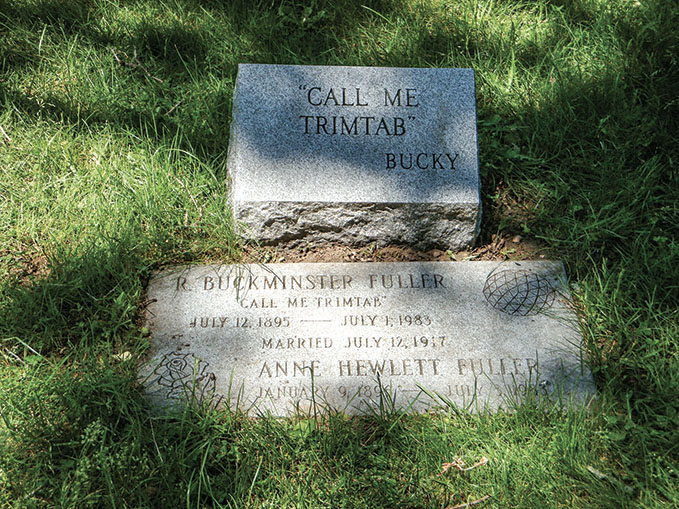

Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983)

Mt. Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Fuller is known for his development of the geodesic dome and other futuristic concepts that involved everything from prefab housing to automobiles. The United States Postal Service issued a postage stamp in his honor in 2004.

He is buried in his family’s plot with a marker incorporating a geodesic dome and his epitaph, “Call me Trimtab”—a term Fuller often used as a metaphor for leadership and personal empowerment. In sailing and aviation, trim tabs are devices attached to major control surfaces that, despite their small size, can have a significant impact on the overall heading of the craft being controlled.

John Q. Hejduk (1929–2000)

Oakland Cemetery, Yonkers, New York

Hejduk was a visionary architect and educator. He was dean of the architecture school at Cooper Union in New York for several years, where he assembled a faculty that produced a number of students who subsequently had prominent careers.

His drawings and his many theoretical constructions are legendary, but he also was a practical architect as demonstrated by his reconstruction of the Cooper Union Foundation Building and such projects as the Kreutzberg Tower in Berlin and the Wall House II in Groningen, the Netherlands.

The design of Hejduk’s gravestone was adapted from one of his last drawings. The two crosses were not intended for a gravestone, yet they are appropriate, even providential, in that Hejduk’s son, Rafael, died only a few weeks after his father and is buried with him.

Le Corbusier (Charles Eduard Jeanneret) (1887–1965)

Roqubrune, Cap Martin, France

Even though he never resided in the United States and his work here was limited, Le Corbusier had an enormous impact on American architecture. He is considered one of the pioneers of the modern movement in architecture and his influence on other architects was profound. His only work in the United States, other than his being a consultant on the United Nations Secretariat Building in New York, is the Carpenter Center on the Harvard University campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Regrettably, his concept of tall residential towers built atop expansive park-like spaces, so beautifully executed in his Unite d’habitation in Marsailles, France, became the prototype for many large, and virtually unlivable, public housing projects built across the United States during the 1950s and 1960s.

He is one of the few architects who actually designed his own grave marker, which he did after the death of his wife in 1957. He died eight years later while on one of his frequent swims in the Mediterranean.

His marker stands upon a stone pad overlooking the Mediterranean. Next to an urn is a small structure that houses colorful plaques for his wife and him.

Marion Mahony (Griffin) (1871–1961)

Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois

Mahony was one of the first women to receive an architectural degree. Her early work was in the office of Frank Lloyd Wright where, among other things, she delineated many of the drawings for the ultimate publishing of Wright’s work by Wasmuth in Germany. It was at Wright’s office that she met another emerging architect, Walter Burley Griffin. They married and moved to Australia when their entry had won the competition to design that country’s capital city, Canberra. After several years in Australia, the two moved to India, where Griffin was involved with several projects. After the death of Griffin, Mahony returned to the United States and took up residence with a relative in Chicago. She did little architectural work but wrote a lengthy memoir, The Magic of America.

After her death, her ashes were buried near a family member’s remains in Graceland Cemetery but without any marker. In 1997, through the efforts of a Graceland trustee, John Notz, Mahony’s remains were moved to a burial spot in the cemetery’s new columbarium. The site is marked by a plaque designed by John Eifler, which incorporates flowers drawn by Mahony in the sketch she did for Wright for the Hardy House in Racine, Wisconsin.

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959)

Spring Green, Wisconsin; Taliesin, Scottsdale, Arizona

Wright had a long, productive, and controversial life. Many books havebeen written describing this extraordinarily important, multifaceted, creative, and self-promoting genius. To highlight his prominence, in 1966 the USPS issued a commemorative stamp in his honor.

When Wright died, his body was buried in a small churchyard at the base of his home at Taliesin in Wisconsin. There he joined the remains of his mother and of his mistress, Mamah Cheney, and her two children, who died in a tragic fire at Taliesin. A lovely monument was constructed that consisted of an art glass panel with his name and the inscription: “Love of an idea is love of God.” Next to this was a large bolder resting on edge. Embedded stones outlined his burial site and the entire ensemble was contained within a great circle of sunken stones.

Wright’s third wife, Olgivanna, stipulated that after her death, Wright’s remains be disinterred, cremated, moved to Arizona, and mixed with her ashes. Unbeknownst to local Wisconsin authorities, her wishes were carried out; Wright’s remains were removed, literally in the dead of night, and sent to California. There are still hard feelings about the way the remains of one of Wisconsin’s famous sons were “stolen.” Thus, the Frank Lloyd Wright Memorial Foundation is unwilling to disclose where the comingled ashes were placed at Taliesin West. A portion of these ashes was reportedly cast upon the Arizona desert as well.

Wright had progeny with distinguished architectural careers of their own. His son Lloyd Wright (1890–1978) designed the famous Wayfayers Chapel in Palos Verdes, California. His son John Lloyd Wright (1892–1972), besides his architectural work, created Lincoln Logs for children. Granddaughter Elizabeth Wright Ingraham (1922–2013) also designed several projects. The ashes of Lloyd were scattered at his favorite property high in Santa Monica, California overlooking the Pacific. John’s were scattered in the ocean in front of his house in Del Mar, California. Those of his granddaughter were taken to sites in Colorado and the family cemetery in Spring Green, California.

Henry H. Kuehn, a leading executive in the medical industry before his retirement, has a longstanding interest and involvement in architecture, working with the Society of Architectural Historians and the Chicago Architecture Foundation. This article is excerpted from his book “Architects’ Gravesites.”