A Complete Illustrated History of the Recumbent Bicycle

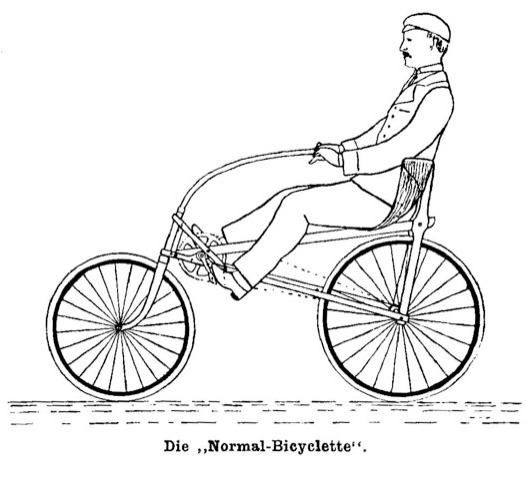

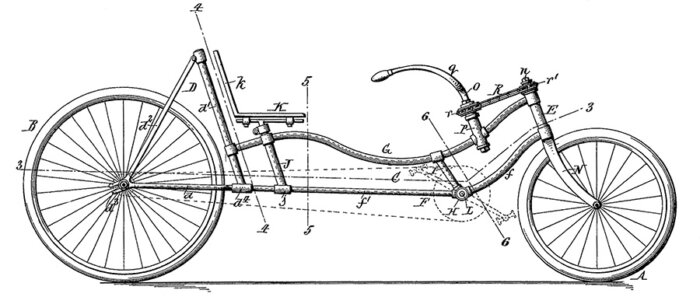

Geared recumbents first appeared in the 1890s, soon after the safety bicycle, which had begun to persuade the more timid riders to return to two wheels. Charles Challand, a professor in Geneva, built what was probably the first geared recumbent. He called it the Normal Bicycle, because the rider’s posture was more normal than that of a stooped-over rider on a standard bicycle. The rider sat directly over the standard-size back wheel, directly steering the smaller front wheel. The crank axle was a few inches behind the steering head.

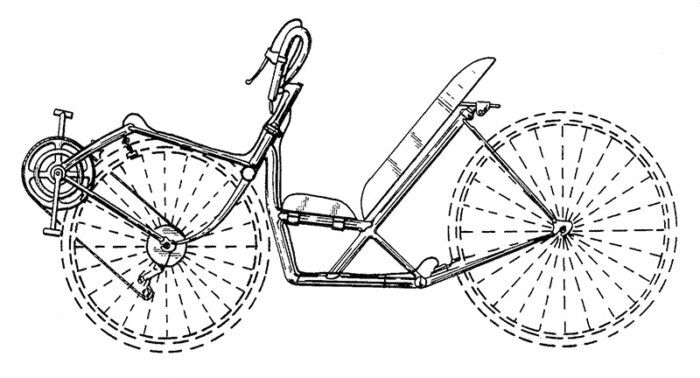

The patent drawing for the Normal Bicycle shows a skid-shoe brake, which was mentioned in a report on a lightweight timber-framed version of the bicycle displayed at the Swiss National Exhibition of 1896. The American consul in Geneva was so impressed by Challand’s machine that he sent a drawing of it to the State Department. According to a report published in the New York Times on October 25, 1896, the bike had been tried in the streets of Geneva and had made a favorable impression.

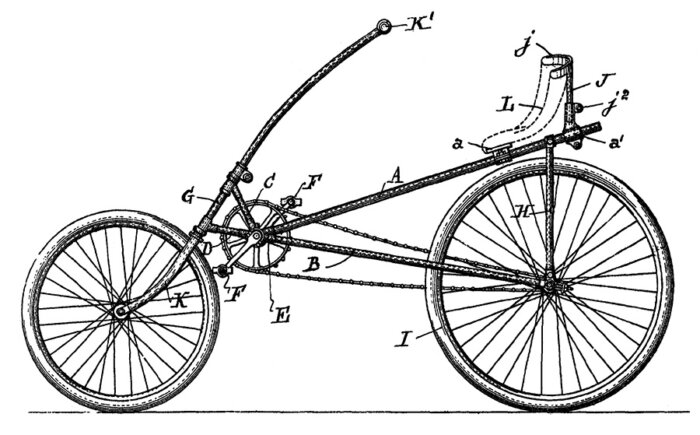

Around that same time, in 1896, Irving Wales of Rhode Island applied for a patent for a recumbent bicycle. Wales’s machine had wheels of equal size and, like the Normal Bicycle, had its cranks behind the steering head. In addition to the standard pedal drive, there was hand drive, which the rider used in the same way as a rowing machine, pulling back and releasing sliding handgrips linked to the cranks by cables. (Arm power is a recurring theme in recumbent design but has never proved popular.)

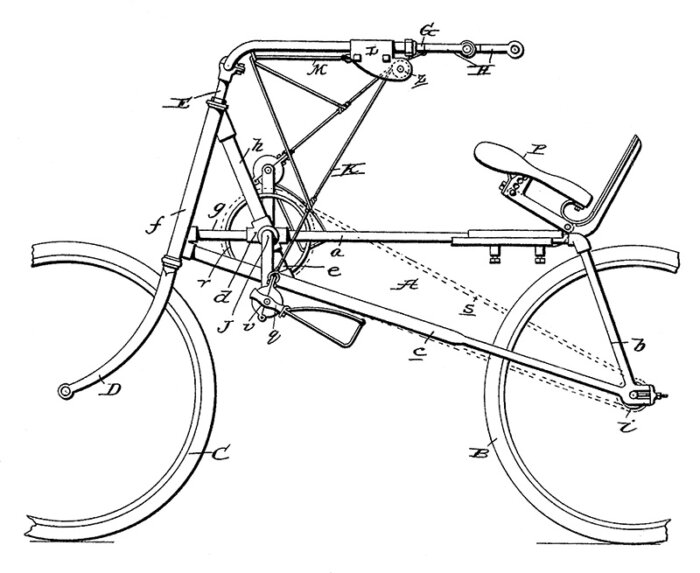

In 1901, an American named Brown took a long wheelbase recumbent called a Sofa Bicycle to England to promote it. The Sofa Bicycle, designed by Harold Jarvis of Buffalo, weighed about 30 pounds and had a standard-size rear wheel and a smaller front wheel, which was steered indirectly by means of a chain-and-sprocket linkage. The seat was ahead of the rear wheel, rather than over it, and the cranks were completely behind the steering head. In a 1902 review of the Sofa Bicycle in The Cyclist, engineer and journalist Horace Lucian Arnold (writing under the name Hugh Dolnar) admitted that it was easy to mount and maneuverable, and that it pedaled and coasted well and was a good climber, but went on to ridicule and dismiss it.

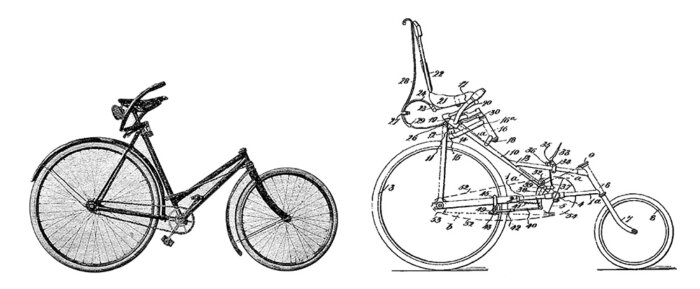

In 1905, P. W. Bartlett of Richmond, England promoted his short-wheelbase recumbent as being as “comfortable as a rocking chair.” Its rear wheel was of standard size, its front wheel much smaller (about 16 inches). Its unique selling point was a chair-like, softly sprung saddle, which Scientific American took note of in its August 1905 issue. The design had been patented in 1902 by Ernest Ames of London on behalf of Leslie John Hamilton Leslie-Miller, an engineer based in Surabaya, Java. The machine is of historic significance for its early implementation of under-seat steering. However, it wasn’t the first machine to be steered in that fashion. The 1896 Humber Open Front ladies’ bicycle (not a recumbent) had had under-seat steering, and the steering system of the Ames/Bartlett recumbent may have evolved from the Humber’s.

In 1914, an Italian named Guglielmo took his long-wheelbase recumbent to Paris to promote it. In general layout that machine was similar to Brown’s Sofa Bike; however, instead of handlebars, it had a steering wheel, which was connected to the steerer tube by a universal joint. The outbreak of World War I put a stop to promotion of this machine, but after the war it was mentioned in Scientific American and in the French periodical Le Commerce Automobile.

In 1914, a long-wheelbase recumbent bicycle, perhaps made by Peugeot, was introduced in France. It had a 26-inch rear wheel, a 22-inch front wheel, and a front end resembling that of a diamond-frame safety, complete with bottom bracket. But the handlebars were where the saddle of a safety would have been; they were linked to the steerer by bridle rods. The rear of the machine had a low-slung frame with a low seat ahead of the rear wheel.

In 1921, an Austrian aeronautical engineer named Paul Jaray (then living in Friedrichshafen, Germany, where he worked for the Zeppelin company) applied for a British patent for a treadle-driven recumbent, which he was granted the following year. Jaray also obtained French and Dutch patents and registered several designs in Germany. Among the options that Jaray proposed were a wrap-around clip-on “skirt” and a removable canopy.

Jaray’s first prototype, built in 1920, had two 26-inch wheels. At first the treadles were linked to the rear wheel by steel cables with return springs, but this was changed to a system in which the cable from the left treadle lever wound several times around a left drum on the rear hub, then onto a horizontal pulley, and then onto a right drum, connecting after several winds to the right treadle lever; this did away with the dead-center problem.

Jaray’s second prototype, built soon after the first, was broadly similar but had a smaller front wheel (about 20 inches) and a much shallower head-tube angle. About 1,300 miles of test riding was done on it. In 1921 the J-Rad was put into production under license in Stuttgart.

About 2,000 were made by Hesperus-Werke GmbH, a subsidiary of the Lufft barometer company. The production version, similar in most respects to the second prototype, weighed about 44 pounds, the comfortable seat contributing about nine pounds. The treadles usually had three steps, giving the effect of three drive ratios (due to the differing leverage) without the complexity of multi-speed gears.

The J-Rad appealed to an educated middle-class clientele rather than to aspiring racers. Comparative measurements by a German physician named Gmelin showed that a rider on a J-Rad had a heart rate about 10 to 12 beats per minute slower when climbing than a rider on a safety bicycle with a four-speed hub gear, even though the J-Rad was about 13 pounds heavier. The British CTC Gazette mocked the machine, but it sold quite well in the Netherlands. Many thousands were produced, but production ceased in 1923 after a decline in build quality and a fatal accident.

The Recumbent Boom of the 1930s

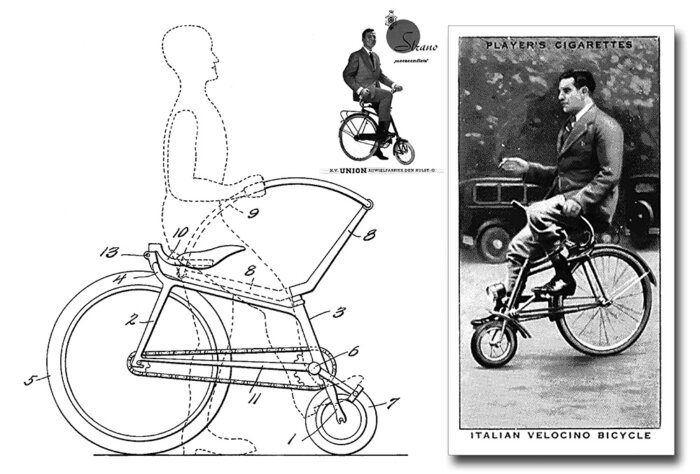

In the mid 1930s there was a wave of interest in recumbents, particularly in Europe. In 1933, Ernesto Pettazzoni, an engineer from Bologna, applied for a British patent for an ultra-short-wheelbase semi-recumbent machine, the Velocino. It resembled a wheelchair chopped in half, with the seat over the normal-sized rear wheel. The tiny front wheel was about 10 inches in diameter. The handlebar was reversible, giving the option of under-seat steering. Mussolini is said to have commissioned the Velocino as a compact, easily stored urban vehicle. The project attracted a lot of attention but was canceled after Italy entered World War II.

In 1964, a Dutch manufacturer called Union produced 1,000 examples of a Velocino-inspired design called the Strano, which had been designed by Bernard Overing of Deventer. (The following year, a German inventor named Emil Friedman exhibited a somewhat similar machine, the Donkey cycle). In 2011, an Italian company called Abici introduced a 21st-century version of the Velocino. Less well known is the stretched Velocino of 1935, which had a very low seat ahead of the rear wheel, with indirect steering linking to inverted drop handlebars, just ahead of the seat squab.

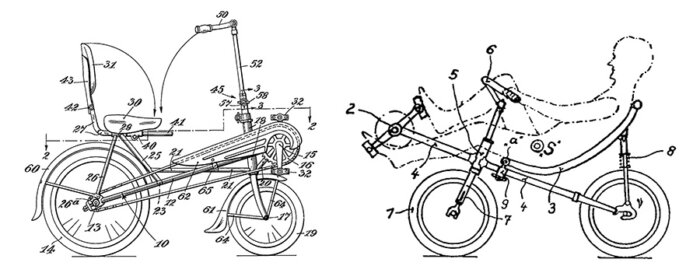

In 1934, F. H. Grubb Ltd of Brixton introduced the Kingston, a long-wheelbase recumbent, with under-seat steering and 20-inch wheels. It had a welded “stretched” diamond frame with a low seat ahead of the rear wheel. Freddie Grubb then built (at his works in Wimbledon) a prototype of a recumbent designed by W. E. Gerrard of Kennington. Completed in the summer of 1936 and called the Velocycle, it had a single main tube instead of a triangulated frame, 20-inch wheels, and a weight of 33 pounds. This was the first bicycle closely to resemble a modern recumbent, having all the elements of the later Avatar 2000: a long wheelbase, small wheels, under-seat steering, multiple gears, and rim brakes. But its influence on later designs is doubtful.

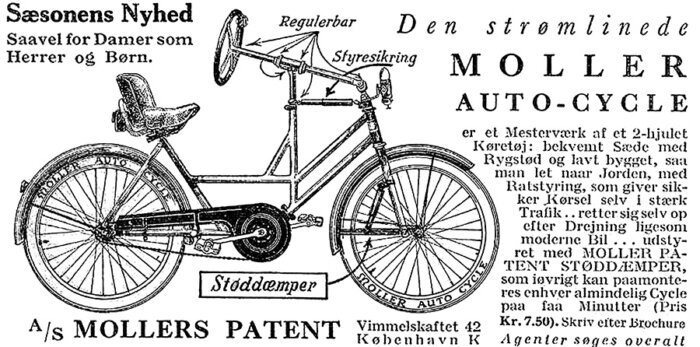

The Moller Auto-Cycle, designed in 1935 by Holger Møller of Copenhagen, was manufactured in very small numbers under license by Triumph in England. The patented aspect of the machine was its indirect steering system. It had a steering wheel, a universal joint linking the steering column to the steerer, a self-centering coil-spring steering damper, a medium-length wheelbase, wheels about 20 inches in diameter, wide-section tires, and leading-link front suspension. The seat was fairly high, ahead of the rear axle. The cranks were at a normal height, midway between the wheels.

The Ravat Horizontal was a French recumbent developed by Henri Martin and built by the Ravat-Wonder factory in Saint-Étienne. Described by Arnfried Schmitz as looking “like the father of all modern short-wheelbase recumbents,” the 1935 sports version had a 28-inch rear wheel and a 20-inch front wheel (nominal sizes) and a frame of Reynolds lightweight tubing. The seat was ahead of the rear wheel and close to the relatively upright head tube. Steering, by means of high handlebars, was direct. The cranks were well ahead of the head tube and the front wheel. In the U.K., this machine was sold in very small numbers under the name Cyclo-Ratio. A number of modern short-wheelbase recumbents, including the Lightning P-38, are similar in configuration.

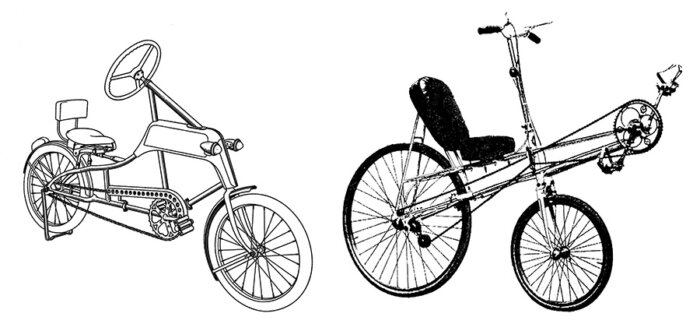

Another recumbent of the mid 1930s, unusual in that it was American, was the Pedi-Plane, designed by Earl Boynton of New Jersey. This was a long-wheelbase machine with a low riding position, wheels about 20 inches in diameter, and a complex indirect steering mechanism with a steering wheel.

Charles Mochet’s Vélo-Vélocars were the most successful and influential recumbents of the 1930s. Mochet started his company in 1920 to build sporty two-seat gasoline-powered cyclecars. After building a pedal-powered version for his son, he began to manufacture similar machines. They were so successful that Mochet then introduced a range of models for adults. Mochet’s pedal cars, called Vélocars, sold for about the same price as a motorbike but were cheaper to run and maintain. Mochet produced about 6,000 Vélocars, some with four wheels and some with three, between 1925 and 1944.

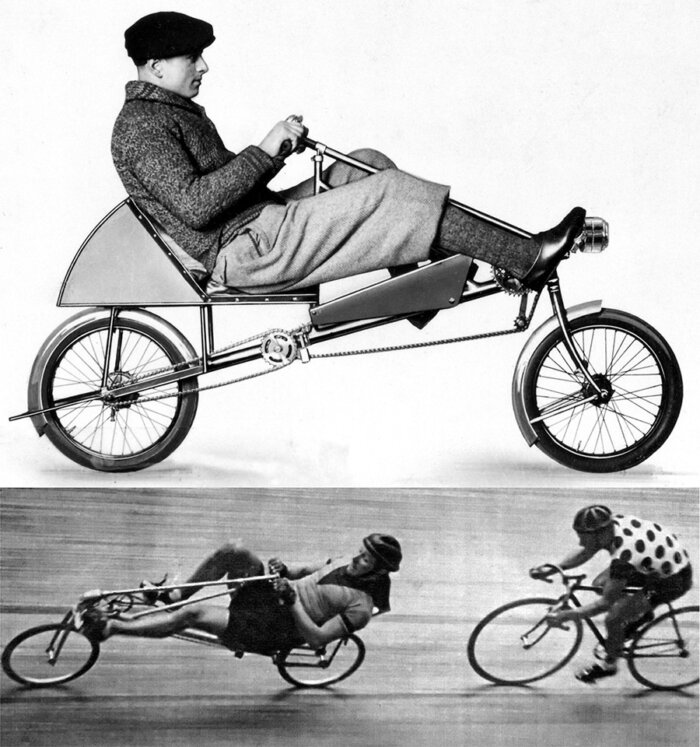

Mochet tried to promote the Vélocar by racing it at velodromes, but neither the four-wheel version nor the three-wheel version handled well on a velodrome’s banking. So he decided to make a recumbent bicycle that would be, essentially, a four-wheel Vélocar cut in half down the middle. He called it the Vélo-Vélocar. In 1932, the Vélo-Vélocar was awarded the Grand Prix Lepine for its patented “indirect steering for recumbent cycles.” In the autumn of 1932, through the Union Vélocipedique de France, Mochet sought confirmation from the Union Cycliste Internationale that the Vélo-Vélocar complied with UCI regulations. The reply was affirmative. The next summer, Francis h, a second-rate rider, broke the 5-kilometer, 10-kilometer, 20-kilometer, 30-kilometer, 40-kilometer, and 50-kilometer records and the hour and half-hour records on an unfaired, fully recumbent racing version of a Vélo-Vélocar.

It is significant that development of the Vélo-Vélocar arose from “the need for speed,” whereas previous recumbent bicycles appear to have been designed primarily for comfort. Francis Faure’s speed records clearly demonstrated that the Vélo-Vélocar was significantly faster than a conventional bicycle. In February of 1934, the UCI set up a committee to define and enforce a new definition of the bicycle. The barely hidden agenda was to ensure the exclusion of recumbents. On April 1, 1934, the UCI’s committee published its definition of a racing bike. It stated that the bottom bracket could not be more than 10 centimeters ahead of the nose of the saddle, thus ensuring that only upright bicycles could be raced under UCI rules. Charles Mochet died soon afterward.

Charles Mochet’s widow and son and one of Charles’s cousins kept the firm going. In 1934, Manuel Morand put in impressive performances on a Vélo-Vélocar in six road races: Paris-Angers, Paris-Vichy, Paris-Troyes, Paris-Soissons, Paris-Limoges, and Paris-Contres. In a major 1934 endurance event, the Concours des Pyrenées du Touring Club de France, one of Mochet’s workers, Henri Martin, demonstrated that, even though his eight-speed touring Vélo-Vélocar weighed nearly 45 pounds, he could outperform many riders of conventional bikes in the mountains. Martin went on to develop the Ravat Horizontal.

Vélo-Vélocars were in production from 1932 until 1940. About 400 are thought to have been produced. There were standard, touring, and track versions, most with equal-sized wheels 18–22 inches in diameter. Balloon tires were used on all but the track versions. The wheelbase was relatively long. The cranks were behind the steering head. The frames were of seamed and welded 40-millimeter steel tubing. The first models had an expensively made bevel drive between the steering column and the steerer. In 1933, seeking a cheaper alternative, Charles Mochet applied for a patent for a simple universal-joint linkage. This was used in the Vélorizontals, a budget range of Vélo-Vélocars supposedly built under license but in fact made by Mochet’s company. A Vélorizontal had a single chain in place of a Vélo-Vélocar’s two-stage drive with countershaft. Some Vélorizontals had a larger 26-inch rear wheel.

The Vélo-Vélocar’s race-bred technical refinement and sporting successes made it the most influential of the 1930s’ many recumbent designs. Its influence was far greater than the relatively small production figures might suggest. Many of the designs mentioned above, including the Ravat Horizontal, the Grubb Kingston, and the Gerrard Velocycle, were inspired by it. The Swiss record breaker Oscar Egg responded by building a streamlined recumbent, hoping to become the first cyclist to exceed 50 kilometers in an hour. But it was Francis Faure, in a streamlined Vélo-Vélocar, who first achieved that, in March of 1939.

In the April 6, 1934 issue of Cycling, A. C. Davison argued that the Vélo-Vélocar should not be banned: “If it does not live up to its reputation, riders will soon cease to try for records and no harm will be done,” Davison wrote. “If it does prove speedier the public, who are the final arbiters, will call it a bicycle whether the legislators approve or not, and will go to see it ridden.” Davison also addressed the question of what bicycles of this kind should be called in English. He concluded that, rather than “low-bike” (which he detested), people should call the new machine a “bicycle”; a new name would then have to be found for the conventional machine (much as the name “ordinary” had been coined for the previously dominant type, the high-wheeler).

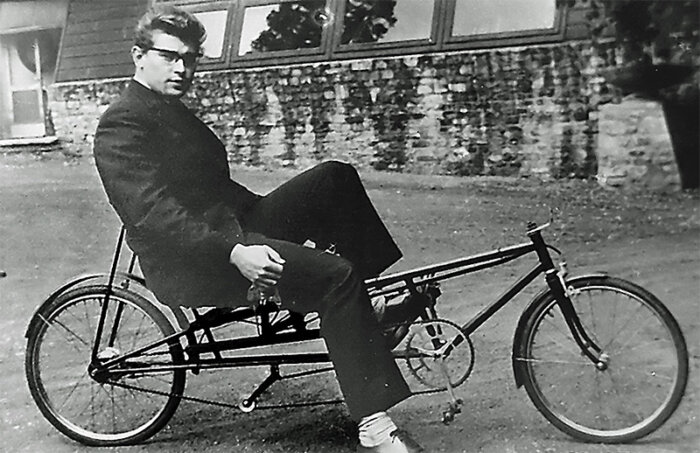

In Cycling’s issue of August 10, 1934, Davison revealed his ideas for what he now called “a recumbent bicycle.” Built almost entirely from standard parts, it should have 20-inch wheels with balloon tires, a wheelbase of 62 inches, a low seat ahead of the rear wheel, and under-seat steering. Davison pleaded for some British manufacturer to take up his ideas and “try to get ahead of the foreign manufacturers for once.”

Recumbents After World War II

In 1946, Jack Fried of New York applied for a patent for a compact recumbent but his design doesn’t appear to have been put into production. For several decades, there was little development of recumbents in the West. But work on recumbents continued in East Germany after 1948. Paul Rinkowski worked for a state-owned rubber manufacturer and had an opportunity to develop his own radial-ply tires for lower rolling resistance. His short-wheelbase recumbents, with wheels of equal size, were not unlike the Ravat Horizontal in general arrangement. An early prototype with 22-inch wheels combined conventional pedal-and-chain drive with arm-operated levers, but Rinkowski soon dispensed with the complications that the arm drive added and settled on 20-inch wheels. In 1953, to protect the design, he applied for an East German patent. Rinkowski proposed mass production of these machines to the East German state, but his suggestion was turned down; the bureaucrats didn’t think the public would accept the design.

As readers of the first edition of Whitt and Wilson’s “Bicycling Science” will recall, an American experimenter, Captain Dan Henry, built a long-wheelbase recumbent with sprung 27-inch wheels in 1968. Henry’s use of a full-size front wheel was unusual, even on a long-wheelbase machine. A short-wheelbase recumbent typically has a small front wheel because the rider’s legs or feet are above the wheel yet must reach the ground when the machine is stationary. Most long-wheelbase recumbents also have a small front wheel. As Wilson explains, there are two reasons:

Although smaller wheels prima facie have higher rolling resistance, this is proportional to load, and the front wheel of a long-wheelbase recumbent is lightly loaded. Smaller wheels are lighter, have less air resistance, and provide nimbler steering.

The Recumbent Revival of the 1970s and Its Aftermath

In 1967, David Gordon Wilson organized a cycle-design competition in conjunction with the British journal Engineering. First prize, announced in 1968, went to the Bicar, a recumbent designed by W. G. Lydiard. In 1972, this stimulated H. Frederick Willkie II of Berkeley, California to build a short-wheelbase recumbent called Green Planet Special 1, which he based on an outline design by Wilson. Although neither Willkie nor Wilson was aware of it at the time, Green Planet Special 1 was much like the Ravat Horizontal of the 1930s. Willkie’s observations during test riding led to a revised design with lower cranks, the small front wheel moved back to clear the rider’s heels, and under-seat steering. Wilson modified this further, changing the seat, the wheelbase, and various aspects of the machine’s geometry. The third version, called the Wilson-Willkie, was fitted with a fiberglass trunk. Ridden thousands of miles, it attracted much interest.

The most significant factor in the rebirth of recumbent bicycle development after 1975 was the establishment and influence of the International Human Powered Vehicle Association (IHPVA). Wilson was an early supporter of the group and became one of its original directors. In 1975, eight recumbents were entered in the IHPVA’s first International Human-Powered Speed Championship. In the next few years, interest in recumbents grew exponentially. Between 1975 and 1980, dozens of other recumbent bicycles and tricycles were raced in human-powered vehicle (HPV) events.

Wilson continued developing the Wilson-Willkie with Richard Forrestall of Fomac, Inc. In 1978 it was put into commercial production under the name Avatar 1000. A long-wheelbase version, the Avatar 2000, was introduced the following year. The Avatar 2000 tracked better than the 1000 in ice and snow, owing to the lower loading on the front wheel, and it braked better.

In 1980, Wilson took an Avatar 2000 to the European Cyclists’ Federation’s Velo-City conference in Bremen. Richard Ballantine, author of “Richard’s Bicycle Book,” saw it there and subsequently bought an Avatar. Derek Henden modified Ballantine’s machine for racing, fitting it with a fairing. In 1982, Tim Gartside rode that machine (which had been dubbed Bluebell) in the International Human-Powered Speed Championships in Irvine, California. At the time, the Vector, a streamlined tricycle designed in 1980 by Dan Fernandez, John Speicher, Doug Unkrey, and Al Voigt, was the machine to beat in HPV races, and most of its competition came from low-slung streamlined tricycles inspired by it. But after the 1982 successes of Bluebell and another streamlined recumbent bicycle, the Easy Racer, the fashion changed, and streamlined recumbent bicycles became dominant in HPV racing.

The Easy Racer was designed by Gardner Martin, whose first HPV, built in 1975, was a recumbent that put the rider in a prone position. Such a position had been tried in 1917, and perhaps earlier. In 2012, Graeme Obree experimented with a similar design. In 1976, with his wife Sandra, Gardner Martin began developing a recumbent with a more practical riding position. This became the Easy Racer, a long-wheelbase small-wheel recumbent. Fred Markham set several new HPV world speed records on Easy Racers. The Martins also marketed an everyday version called the Tour Easy. Partially faired Tour Easy machines won the 1982 and 1983 practical-vehicle contests at the International Human Powered Speed Championships. Riding an Easy Racer Gold Rush, Fred Markham won the $25,000 DuPont Prize for the first HPV to exceed 65 miles per hour. Today he owns Easy Racers Inc., one of the two Californian recumbent manufacturers that participated in the International Human Powered Speed Championships in the 1970s and are still extant. The other surviving manufacturer is Lightning Cycle Dynamics, founded by Tim Brummer.

In 1979, three students at the Northrup Institute of Technology in Inglewood, California — Tim Brummer, Don Guichard, and Chris Dreike — built the first version of their Lightning recumbent. Two years later, Brummer won the Abbott Prize for the first human-powered vehicle to exceed the highway speed limit of 55 miles per hour, riding the Lightning with a 700C back wheel, a 20-inch front wheel, the crank ahead of the front wheel, and direct front-wheel steering with conventional handlebars. In 1986, the Lightning exceeded 64 miles per hour at sea level before the Easy Racer achieved 65 mph at an altitude of 7,000 feet. In 1989, the Lightning placed first in the Argus Tour, a 65-mile race around the cape of South Africa, ahead of 15,000 other machines, many ridden by professional cyclists. Brummer’s cycles have held world records and have won the HPV Race Across America, beating the Easy Racer while averaging more than 25 miles per hour for 2,200 miles.

The commercially produced Avatar, Tour Easy, and Lightning recumbents had many imitators. Although no recumbent has ever achieved mass-market popularity, and although Avatars are no longer made, there is a wide choice of specialist machines. Recumbents are manufactured in the United States, in Australia, in Germany, in the Netherlands, in Switzerland, in Poland, in Taiwan, and in the U.K.

One reason why recumbent cycling didn’t really come of age until the early 21st century was that certain technological developments were needed. For example, the seats of many early machines were less than ideal, whereas today’s glass-fiber and carbon-fiber moldings are close to perfection. The wide-range indexed gears that were developed for mountain bikes certainly helped, too. But arguably the most important technological development was the clipless pedal — on some recumbents, undoing a toe trap while riding was virtually impossible.

Whereas diamond-frame safety bicycles varied relatively little from one another, by the early 2000s recumbents came in many shapes and sizes, and there were marked regional differences. In the United States, where the modern recumbent movement started, the long-wheelbase design was still by far the most popular, but in Europe long-wheelbase recumbents weren’t often seen. Recumbent bicycles were especially suitable for the Netherlands, a country with strong winds, no mountains, and many cycle paths. A cyclist in a velomobile (a fully enclosed three-wheeler) could go twice as fast as a traditional Dutch bicycle and not get cold or wet.

Most recumbents of the early 21st century were short-wheelbase derivatives of the Ravat Horizontal, but there were quite a few other designs, including “high racers” with twin 700C wheels, “traditionals” with 20-inch front wheels and 26-inch rear wheels, and “low racers,” often with the same wheel configuration as a “traditional” but a longer wheelbase to allow the seat to be mounted lower. Also catching on around the world were low unfaired three-wheelers, once rarely see outside the U.K.

Much of the growth in the popularity of recumbents could be traced back to the first international HPV speed trials, held in England in 1980, and the subsequent media coverage, which sparked interest in Germany and the Netherlands. It was estimated that by 2006 there were 50,000 recumbents in the latter country.

Early-21st-century recumbents could be broadly classified into three main categories: long-riders, short-riders, and low-riders. A long-rider is a long-wheelbase machine with either above-seat or under-seat steering and usually with a chain driving the rear wheel. Long-riders (which can be traced back as far as Harold Jarvis’s patent, applied for in 1901) were revived in the 1970s in the forms of the Avatar 2000 and Tour Easy. A short-rider has a shorter wheelbase and either above-seat or below-seat steering. Most short-riders have chain drive to the rear wheel, but some drive the front wheel by means of a flexing chain or cranks that move with the steering. The Ravat Horizontal of the 1930s was a classic early short-rider. Thomas Traylor’s 1982 design was an early front-drive short-rider.

Low-riders typically have seat backs at 30º or less to the horizontal. Most have a medium- length wheelbase and cranks ahead of the front wheel.

Not all recumbents fit neatly into these categories. For example, the Burrows Ratcatcher, launched in the late 1990s, is somewhere between a short-rider and a low-rider. In its standard form it was faster than most recumbents yet fine for day-to-day riding. On the other hand, it wasn’t particularly suitable for urban cycling or for speed-record attempts.

A few recumbents can be folded for portability. For example, in the 1980s Linear offered two models with folding frames, one called the SWB Sonic and one called the LWB. One of the best-known folding recumbents of recent years was the Bike Friday SatRday, which could be bought with either under-seat or above-seat steering. A conversion kit was produced to convert a Brompton folding bicycle into a recumbent.

If recumbents have manifest technical advantages, why are so few of them sold? One reason is that cyclists “follow each other like sheep,” as Paul de Vivie, who wrote as Vélocio, pointed out in 1911. The vast majority are still accustomed to the conventional riding position. Another reason is that it is widely thought that recumbents are more difficult for motorists to see in traffic, and that therefore recumbent riders are at more risk than riders of conventional bicycles. This view is fiercely contested by many advocates of recumbents, who point out that the eye level of a recumbent’s rider is typically quite close to that of someone driving a sedan. Nonetheless, the suspicions of the cautious may be reinforced by the sight of recumbent riders using pennants on masts to make themselves more conspicuous. But whether or not recumbents are as visible to motorists as conventional bicycles, the fact remains that they are widely thought to be less conspicuous.

But perhaps the greatest problem that has hindered the recumbent movement for generations is the lack of a mass-produced front-wheel multi-speed gear hub with integral cranks and pedals. In most recumbent configurations, the ergonomically appropriate place to pedal would be the front wheel, as on the Parisian velocipedes of the 1860s. But without such a hub the pedals always had to be placed in front of that wheel, above it or behind it, disabling compactness, an upright position, or easy starting. A new company in France, Kervelo, now produces hub gears with integral cranks and up to 12 speeds, but still at high, short-series cost that would easily double a recumbent’s price. What the recumbent may ultimately need is a Steve Jobs-like innovator — one who can highlight, refine, and market its enduring plus points: convenient sitting, raising the thrust onto the pedals, lowering the frontal area (and therefore air drag), and reducing the drop height and risk of bone fractures.

Tony Hadland is the author of, among other books, “Raleigh: Past and Presence of an Iconic Bicycle Brand” (Van der Plas/Cycle Publishing). He is the co-author (with Hans-Erhard Lessing) of “Bicycle Design: An Illustrated History,” from which this article is excerpted.

Hans-Erhard Lessing, formerly a Professor of Physics at the University of Ulm and a Curator at the Technoseum Mannheim and the ZKM Karlsruhe, has written biographies of Karl Drais and Robert Bosch as well as books on bicycle history.