Butch Heroes: Portraits From Queer History

When Ria Brodell began researching what would become their book “Butch Heroes,” they scoured the LGBTQIA sections of local libraries, including the Boston Public Library and the libraries at Tufts University and Boston College. “I was looking for people in history with whom I can personally identify — people who were assigned female at birth, had documented relationships with women, and whose gender presentation was more masculine than feminine,” Brodell explains in the book’s introduction. Though some of Brodell’s subjects might today identify as “lesbian,” “transgender,” “nonbinary,” “genderqueer,” or “intersex,” these terms were obviously not available to them during their lifetime. The term Brodell chose for these figures, “butch,” reflects the duality of what has historically been slung as both an insult and a congratulatory recognition of strength.

From a Swiss surgeon of the Napoleonic Wars to a lieutenant of the Mexican Revolution, each brief biography in “Butch Heroes” — there are 28 in total, a handful of which we’re pleased to present below — is paired with a portrait modeled in the style of Catholic holy cards. The portraits function, explains the author, as a subversive way to reverentially present the lives of the book’s subjects, “especially because so many of them were accused of ‘mocking God and His order’ or deceiving their fellow Christians.” In this way, “Butch Heroes” spotlights strong, brave people in the way they lived their lives and challenged their societies’ strict gender roles.

—The Editors

D. Catalina “Antonio” de Erauso

Catalina de Erauso was born in San Sebastián, Spain, to a noble Basque family. She was raised in a convent from an early age but before taking her vows fled dressed in men’s clothes and assumed the name Francisco de Loyola.

Francisco worked as a page for a few years before deciding to seek adventure in the New World, sailing to Panama as a cabin boy. After arriving in New Spain, he enlisted in the Spanish army under the name Alonso Díaz Ramírez de Guzmán. He became a successful soldier in Chile and Peru, even advancing to the rank of captain. However, like many other soldiers, he got into frequent brawls, had trouble with women, and accumulated gambling debts. After deserting the army, pursued by authorities for various offenses, including murder, he was eventually wounded in a duel. Believed to be on the verge of death, he revealed that he was a woman and was placed in a convent.

After recovering and trying to escape, Erauso confessed everything to a bishop and was examined by midwives, who found that she was indeed a woman and a virgin. Released, she traveled back to Spain, but the story had spread and Catalina de Erauso became a celebrity known as the “Lieutenant Nun.” She petitioned King Philip IV for a military pension, citing her 15 years of service to the crown in New Spain. She also visited Pope Urban VIII with a request to be allowed to continue to dress as a man, referencing her status as a virgin and her defense of the Catholic faith.

With the permission of the pope and a pension from the Spanish government, Erauso returned to New Spain as Antonio de Erauso and retired as a mule driver and merchant.

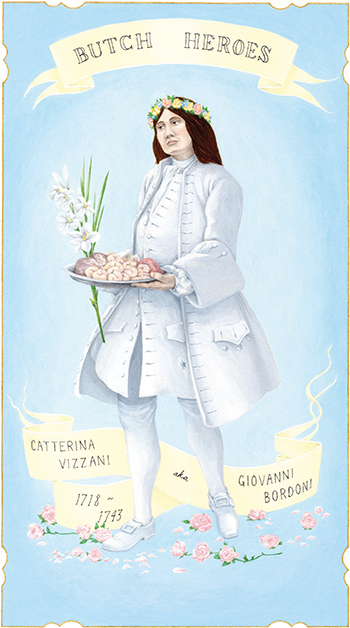

Catterina Vizzani (aka Giovanni Bordoni)

Catterina Vizzani was born in Rome to a carpenter’s family. At age 14 she fell in love with a girl who was teaching her embroidery. Catterina began to dress in men’s clothes and visit the girl’s window at night. Their relationship lasted for over two years, until the girl’s father found out and threatened to turn Catterina over to the courts.

Catterina left Rome, dressed in men’s clothes, and took the name Giovanni Bordoni. With the help of a priest, he got work as a vicar’s servant in Perugia. The vicar was an austere man and complained of Giovanni “incessantly following the Wenches, and being so barefaced and insatiable in [his] Amours.” It was rumored that Giovanni was the best seducer of women in that part of the country. This reputation did not make the vicar happy, and he complained to the priest who had recommended Giovanni. The priest wrote to Giovanni’s parents, who in turn told the priest everything. After learning the truth, the priest decided to keep Giovanni’s secret.

After four years with the vicar, Giovanni left Perugia for Montepulciano, where he fell in love with the niece of the local minister. The minister was very protective of his niece, so the couple planned to secretly travel to Rome in order to be married. This plan was found out, and they were intercepted on their journey. During his attempt to surrender, Giovanni was shot in the left thigh, four inches above his knee.

In the hospital, suffering from gangrene, Giovanni’s wound grew so painful that he was forced to remove the “leathern contrivance” that had been fastened just below the abdomen and hide it under his pillow. On his deathbed he revealed to a nun that he was female and a virgin, and requested the ceremonial burial given to virgins. The body was laid out in the proper habit of a woman, with the virginal garland on the head and flowers strewn about the clothes.

A surgeon and professor of anatomy at Siena, Giovanni Bianchi, dissected the body in an attempt to find an explanation for “those who followed the practices of Sappho.” He examined it extensively, including removing and dissecting the hymen, clitoris, fallopian tubes, intestines, colon, gall bladder, and liver, finding everything in its “natural state.”

Catterina/Giovanni’s funeral procession was extremely popular; people flocked from all parts of the city to get a view of the corpse. There were even attempts at canonization.

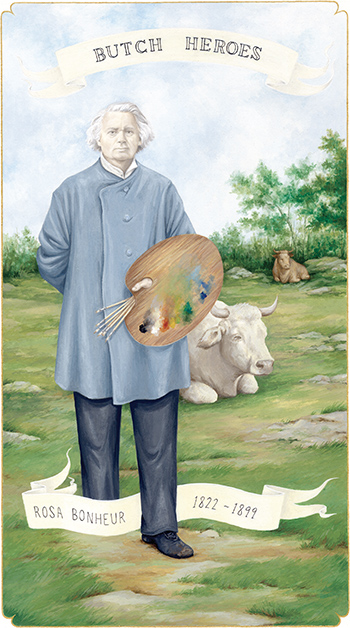

Rosa Bonheur

Rosa Bonheur was a 19th-century French painter and sculptor. She was one of the first renowned painters of animals and was the first woman to be awarded the Grand Cross of the French Legion of Honor. An extremely popular artist during her lifetime, she exhibited at the Paris salon regularly.

Often mistaken for a man because of her short-cropped hair and strong features, she was granted permission by the police commissioner to wear men’s attire while painting. She was married twice, first to her childhood sweetheart Nathalie Micas in a private family ceremony conducted by Nathalie’s father, and after Nathalie’s death to American artist Anna Klumpke.

Bonheur was extremely successful financially. This allowed her to purchase Château By, a house and farm, near the Fontainebleau Forest and to pay off her father’s debts. She also supported her siblings throughout her life, despite their objections to her lifestyle. Bonheur consistently defended her independence and her relationships with Micas and Klumpke. She used her last will and testament to force legal recognition of her right to transfer her property to another woman.

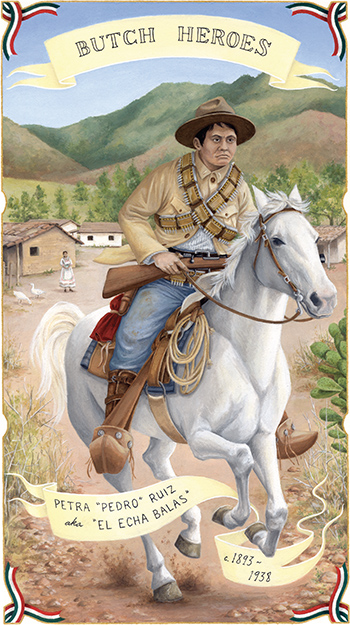

Petra “Pedro” Ruiz

According to the National Defense Archives in Mexico City, Petra Ruiz was born in Acapulco in December 1893 and died in Mexico City in February 1938. Petra is recorded as enlisting in the Constitutionalist Army in 1913 under the name Pedro Ruiz. The disguise — male clothing and short, cropped hair — was so perfect that no one was suspicious. Pedro Ruiz quickly rose to the rank of lieutenant, fighting for Venustiano Carranza against Victoriano Huerta’s forces.

Lieutenant Ruiz soon established a reputation as an accomplished fighter with a thirst for adventure and a violent temper. He competed fiercely for the love of women. His fellow soldiers are said to have feared him, earning him the nickname “El Echa Balas” or “Bullet Slinger” because of his sharp shooting skills and abilities with a knife.

On one occasion Lieutenant Ruiz’s battalion took control of a hacienda while fighting in Oaxaca, killing the owner. The soldiers argued over who would be the first to rape the owner’s young daughter. Hearing her screams, Lieutenant Ruiz rode in with guns blazing and said, “I’m taking this one, and if any of you don’t like it, you can tangle with me!” The soldiers backed off, and Lieutenant Ruiz rode off with the girl. Once they were far enough away, Lieutenant Ruiz opened her shirt to reassure the girl that she was safe, saying, “I’m also a woman like you.” Upon reaching the nearest town, she left the girl with a family who would keep her safe. She was later quoted as saying, “I joined the Constitutionalist Army as a way to survive, but above all, to avert whenever possible the rape of more women, such as the one I suffered.”

Toward the end of the war, newly instituted President Venustiano Carranza was reviewing the troops, and as he was walking past, Lieutenant Ruiz stepped forward and said, “Mr. President, since there’s no more fighting, I want to ask for my discharge from the army, but first I want you to know that a woman has served you as a soldier.” Those assembled were amazed, and Carranza immediately called for an investigation into the life of Lieutenant Ruiz.

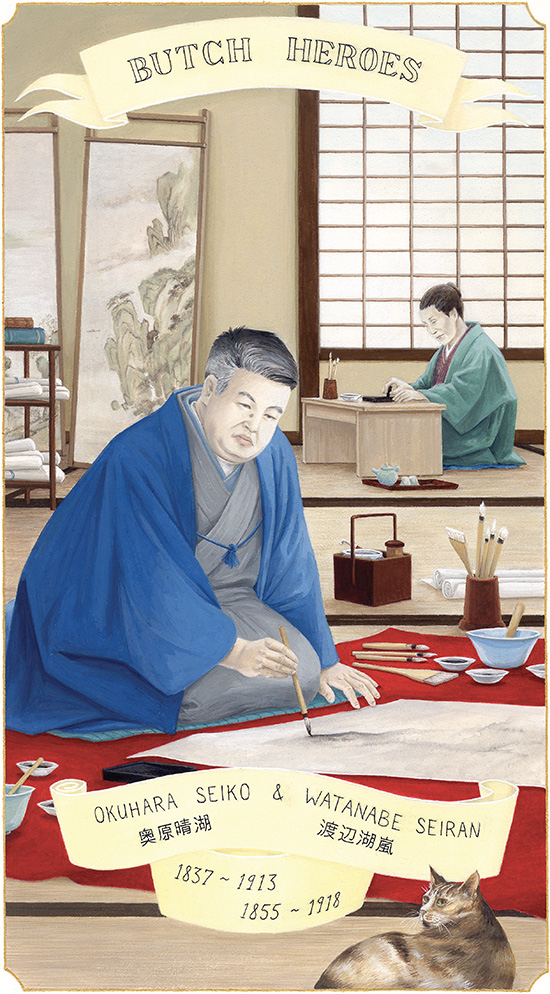

Okuhara Seiko & Watanabe Seiran

Okuhara Seiko was a literati artist of the late Edo and early Meiji period. A painter, calligrapher, poet, teacher, and martial artist, Seiko was born with the name Setsuko in the domain of Koga, to a high-ranking family of the samurai class. Young Setsuko would normally have been subjected to an arranged marriage, but her class allowed for some freedom. Girls were not permitted to study painting as apprentices in the traditional workshop studios, so instead Setsuko received private training from various artists and scholars, gaining a well-rounded and diverse literati education.

At 28, Setsuko wished to move to the capital of Edo (now Tokyo) to begin a career as an artist. However, laws in late Edo-period Koga forbade women from leaving the clan lands, so Setsuko arranged to be adopted by an aunt in the neighboring clan of Sekiyado, which had no restrictions on women’s travel.

Shortly after arriving in Edo, around 1865, she changed her name from Setsuko to Seiko, a name that gives no indication of gender, meaning “clear lake.” Seiko was a masculine, robust figure, wearing men’s clothes and short hair in a male style. A gregarious personality, quick wit, creativity, and penchant for conversation made Seiko an extremely popular and sought-after personality at scholarly gatherings and parties. It did not take long for Seiko to become an established artist. Seiko was the first female artist to have an audience with the Empress, and Seiko’s home became a favorite gathering place for artistic and literary leaders of the day.

Seiko opened a coed school in the early 1870s. Seiko believed that girls who were serious about their education needed a place to study away from the demands of home. The school grew, reaching upward of 300 students, including geisha.

Watanabe Seiran, originally one of Seiko’s students, was Seiko’s companion of more than 40 years. Seiran was a talented painter in her own right. Not only did she manage the household and studio affairs, but she helped with the creation of commissioned works and the training of students. She was also responsible for the numerous study works and sketches necessary for the completion of paintings. Seiran emulated Seiko’s style so perfectly that it is difficult to tell their work apart without a signature.

Ria Brodell is an American artist, educator, and author based in Boston. This article is excerpted from Brodell’s book “Butch Heroes.”