The Powerful Case for Redefining Alzheimer’s Disease

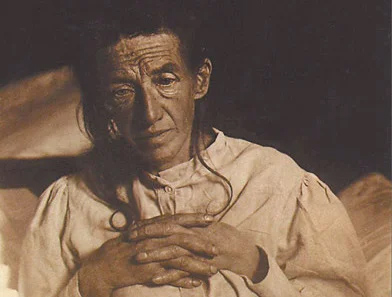

The signature case of Alzheimer’s disease was a German woman named Auguste whose mental status began to deteriorate to the extent that her husband brought her to a psychiatry clinic in Frankfurt. As is traditional, the scientific literature until very recently referred to Auguste merely by her first name plus the initial of her last name — Auguste D. She was seen at the Frankfurt psychiatric hospital in 1901, and her attending physician at the time was a young 30-something anatomist turned psychiatrist, Alois Alzheimer. Alzheimer came to this case from early interests in the structure of the brain, basically its anatomy and cellular structure. This very structure-based view of brain function was the context he brought to his clinical experiences in psychiatry, a craft he learned under the guidance of Dr. Emil Sioli in Frankfurt-am-Main.

In April 1906, his old mentor Dr. Sioli sent word to Alzheimer that Auguste D. had died. Alzheimer was pleased to learn that Sioli had arranged for an autopsy and had sent tissue from the brain of the deceased woman to Munich for Alzheimer to examine.

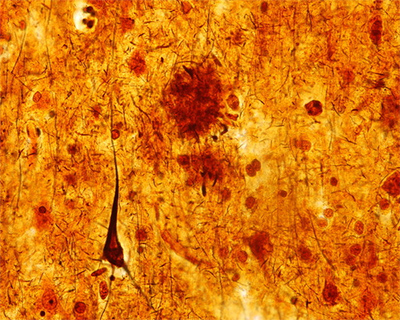

Two features of the preparation in particular caught his eye. The first he described in this way: “Throughout the whole cortex … one finds miliar foci, which are caused by deposition of a peculiar substance in the cortex.” The “peculiar substance” we now know was a waxy form of aggregated protein known as amyloid. The “depositions” would come to be known as amyloid plaques. The second feature he described thusly: “very peculiar changes in the neurofibrils … only a tangle of fibrils indicates where a nerve cell had been previously located.” These peculiar neurofibrils are actually aggregates of a different protein known as tau. We now refer to these aggregates as neurofibrillary tangles.

In this way the odd deposits now known as plaques and tangles became tightly linked to a specific form of dementia. Alzheimer made detailed notes on his discovery and took them to his superior, Emil Kraepelin. He was quite certain that the plaques and tangles were the explanation for the highly unusual behavior of Auguste D. Kraepelin apparently liked the idea enough that he suggested that Alzheimer present his findings at a meeting of German psychiatrists in the fall of 1906. Alzheimer agreed and went to Tübingen that fall to announce his discovery.

The original observation was an important case study, but it was elevated to the level of a disease for reasons that were strategic, not scientific.

The story might have ended here as a long-forgotten case study gathering dust in the archives of medicine. Alzheimer’s boss Kraepelin, however, had other ideas. He too was a believer in the idea that psychiatric disease was caused by changes in the physical structure of the brain. The novel plaques and tangles that Alzheimer had found in the brain of Auguste D. neatly fit that philosophy. Kraepelin was very well-known at the time, in part because he was the author of a widely used textbook, “Psychiatrie.” Kraepelin would periodically update his textbook to include the latest findings (and maybe to sell more books), and, as luck would have it, at the time that Alzheimer published his case, Kraepelin was preparing the eighth edition. To add more support to his own philosophy of the brain, he decided to include the case of Auguste D. in his revision. One might imagine it felt awkward to include a simple case study in a widely used textbook. Kraepelin cleverly solved this problem by elevating the case of Auguste D. to the status of a disease. He called it Alzheimer’s disease, and he included this new condition in the 1910 edition of “Psychiatrie.”

This was a bold and almost reckless move that, in retrospect, had a huge and outsized influence on the field. In most cases, I like it when scientists are bold. Put up a clever argument, and let a smart and informed debate refine it or rebuke it. Either way, science advances. Reckless is not so good. A textbook paragraph is much weightier than the same paragraph in a journal article or a meeting presentation. Textbooks impart a feeling of permanence to an entry. Their contents are imbued with the unspoken assertion that they represent settled art and thus are not easily questioned. Putting Auguste’s condition in a textbook as a new disease comes pretty close to reckless because, on the flimsiest of grounds, Kraepelin was trying to put the “Case Closed” stamp on this telling of what he called Alzheimer’s disease. It was to be the first of three inflations in the definition of Alzheimer’s disease.

Let’s go back and consider Alzheimer’s findings in the brain of Auguste D. Two unusual features occurred together. Unusual deposits, plaques and tangles, were correlated with a highly unusual dementia. One possibility to explain the presence of plaques and tangles in the brain of a person with dementia is the one Alzheimer and Kraepelin favored: The plaques and tangles caused the dementia. That fit well with their philosophies that the function of the brain was governed largely by its structure. It most likely explains why Alzheimer championed this first explanation and why Kraepelin was so eager to promote it. But perhaps Auguste D.’s peculiar dementia caused the brain changes that led to plaques and tangles. The plaques didn’t cause the disease; the disease caused the plaques.

I’ve told the story of Alzheimer and Auguste D. in great detail because it tells us a lot about why the field is stuck and why a successful treatment for Alzheimer’s has been so slow in coming. The original observation was an important case study, but it was elevated to the level of a disease for reasons that were strategic, not scientific. Both Kraepelin and Alzheimer were subscribers to a school of thought that held that the structure of the brain was the key to its function, and that if the structure became littered with abnormal deposits, its function would also become abnormal. Finding plaques and tangles in the brain of a person with dementia fit that idea, and putting it forward as a hypothesis was reasonable. From these origins, however, the two psychiatrists inadvertently biased the thinking of subsequent generations of physicians and scientists. Their assertion that the correlation of plaques and dementia represented a causal relationship — plaques caused the dementia — has proven very hard to shake off, despite the shortage of evidence to support it.

For Alzheimer and Kraepelin, the rare form of early-onset dementia they named Alzheimer’s disease was, they believed, caused by the deposits they had seen in the brain of Auguste D. That first linkage of deposits and dementia was the Trojan horse that released the soldiers of the second inflation. Published in 1976, the article most commonly cited as the manifesto of this effort was written by Robert Katzman and bore the fearsome title “Editorial: The Prevalence and Malignancy of Alzheimer Disease: A Major Killer.” Katzman began his two-page editorial by arguing that there was no really significant difference between the relatively rare condition that was known at the time as Alzheimer’s disease and the far more common condition known as senile dementia. He then went on to argue that dementia was badly underdiagnosed as a cause of death. He estimated that if the cause of death were adjusted to honestly reflect this fact, dementia was arguably “a major killer.” The real purpose of the editorial, however, was to argue for equating senile dementia with Alzheimer’s disease. This was a bit of a stretch.

To bolster his case for their equivalence, Katzman cited earlier clinical speculation that Alzheimer’s disease and senile dementia were similar in their symptoms. He also cited a pair of papers published a few years earlier. Katzman wrote, based on his analysis of these two papers, that when comparing the microscopic appearance of the brain of a person who had died with Alzheimer’s disease with one who had died with the more common senile dementia, “The pathological findings are identical — atrophy of the brain, marked loss of neurons, neurofibrillary tangles, granulovacuolar changes, and neuritic (senile) plaques.”

The problem is that this is not exactly what the two papers had claimed. In fact, five cases with clinical dementia (10 percent of the authors’ subjects) could not be diagnosed with confidence by the microscopic appearance of the brain, and 40 percent had changes that would have led to a non-Alzheimer’s diagnosis. In the end, only “50% were considered to be cases of senile dementia showing the histological features of Alzheimer’s disease.” This is hardly a rock on which to build the claim that senile dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are one and the same.

Katzman’s inflated view of Alzheimer’s disease, however, soon took hold. By 1980, it had earned a place in the third edition of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III).” Subsequently, attempts were made to precisely define the pathology needed for a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Eventually, there were so many “authoritative” sources on how to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease that a well-meaning clinician could surely have been forgiven for getting frustrated about what this newly inflated condition really was and whether it applied to the elderly person sitting in his or her office.

To attempt to deal with this, a working group was assembled under the auspices of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Alzheimer’s Association (then known as the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association — ADRDA) to formalize the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The working group came up with a list of criteria to diagnose what they called “PROBABLE Alzheimer’s Disease [all caps is their emphasis].” But the group went one step further. They established criteria for a diagnosis of “DEFINITE” Alzheimer’s disease. For this score, you first had to have a clinical diagnosis of dementia, using the following five criteria: dementia established by clinical examination; deficits in two or more areas of cognition (problem solving, language, attention, etc.); progressive worsening; no disturbance of consciousness; and onset between ages 40 and 90, most often after age 65. But you also needed “histopathologic [i.e., microscopic] evidence obtained from a biopsy or autopsy.” And what did they consider definitive histopathologic evidence? Remarkably, they didn’t say. Our well-meaning clinician had to wait until the following year when a separate summary of the workshop was published.

The details are important to the aficionado, but it’s the big picture that is important to us. Alzheimer’s disease was to be defined by the presence of plaques. Yet plaques are a feature that is not present in 15 percent of the people with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, and a feature that is present in people of all ages including 30 percent of elderly people without any cognitive impairment. If this doesn’t make sense to you, it’s because it doesn’t make sense.

Alzheimer’s disease is defined by the presence of plaques, a feature that is present in people of all ages, including 30 percent of elderly people without any cognitive impairment.

So, who died and made the pathologist king? There was really no good reason for pathology to trump neurology. You can get a definitive diagnosis of any number of complex brain diseases — autism, depression, schizophrenia, epilepsy, and many others — without any pathological study or live imaging of the brain. If a child psychiatrist diagnoses a young boy as having autism, there is no need for a brain scan to test the psychiatrist’s skill. For the purposes of treatment, the child has autism. If a neurologist diagnoses a person as having Parkinson’s, that’s the diagnosis. They don’t wait with bated breath to find out whether there were α-synuclein deposits in the brain. For the purposes of treatment, the person has Parkinson’s disease. Late-life diseases like Parkinson’s and Huntington’s do have characteristic brain abnormalities, but it is the presentation of the clinical symptoms that allows physicians to have confidence in their diagnosis. To be fair, if an autopsy is done and there are no deposits, the diagnosis is questioned, but not rejected. The clinical diagnosis overrules the pathology. As it should.

Then our clinical trials started failing, our antibody trials in particular. In the basic research laboratories of the world, data kept accumulating that violated the expectations of an amyloid-only definition for Alzheimer’s disease biology. In response the NIA began to recognize that there was a “broad consensus … that the criteria should be revised to incorporate state-of-the-art scientific knowledge.” The result was a truly comprehensive review — a compendium of four papers comprising reports of three working groups plus an introductory summary. Coming as it did, a full quarter century after the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) working group met, it would have been an ideal platform to announce the decision to cut the definition of Alzheimer’s disease loose from the presence of plaques. Instead the experts in the field doubled down and bet the store on amyloid. In doing so, they made the entire situation much, much worse.

Writing the first paper was a clear struggle for its authors. The task before the group was to come up with a recommendation for how practicing physicians should decide whether or not a living person, sitting in front of them in their office, had Alzheimer’s disease. But reading their words, it is quite clear they were not about to be drawn into saying in print that amyloid, or any other “biomarker” (like tau), should be used to define Alzheimer’s disease. They made a clean and explicit separation between a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease dementia and what they called the “pathophysiological process of Alzheimer’s disease.” What the group essentially said was that in the clinic the presence or absence of amyloid is just a piece of information that can be helpful in reaching a diagnosis, and nothing more.

The second paper in the series was important for the attempt of the working group to define what is known as MCI (mild cognitive impairment). The goal was a useful one: to try to clinically identify Alzheimer’s disease as early as possible so that treatment could begin when the probability for meaningful impact was the greatest. These authors were a separate group of neurologists. They too wrestled with how to incorporate biomarkers into their recommendations. In the end, they conclude, “Considerable work is needed to validate the criteria that use biomarkers and to standardize biomarker analysis for use in community settings.” Like the clinicians in the first paper, they are willing to say that people who have no evidence of amyloid or tau are “unlikely” to have MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease, but they add the caveat that “… such individuals may still have AD, … [but for these patients] … a search for an alternate cause of the MCI syndrome is warranted.” As with the first group, the MCI paper is arguing that while evidence of amyloid and tau may be useful information, it is not definitive.

The first two papers had basically said that pathology was only one of several things to consider in reaching a diagnosis. The third paper in the series, however, put the pathophysiology front and center in our definition of Alzheimer’s disease. More than that, however, it exploded our definition of Alzheimer’s disease almost beyond recognition. This is the third inflationary event in the history of Alzheimer’s disease, and unfortunately, compared to the expansions ushered in by Kraepelin and later by Katzman, this third inflation was bigger and more destructive to the field.

It wreaked havoc by “redefining the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease.” This redefinition created what was in effect a totally new stage of the disease process: preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. By “preclinical” the authors meant that people with plaques in their brain (or the wrong amount of amyloid in their cerebrospinal fluid) are not healthy people. They already have Alzheimer’s disease. They just haven’t started to show the symptoms yet. In this telling of the story, the 30 percent of elderly people who have plaques but also have normal brain function are not simply healthy people with plaques. They are sick people without symptoms.

This may seem to be just semantics, but it’s actually an incredibly audacious claim. About 1 in every 10 people over the age of 65 have some symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. That’s 10 percent of the elderly. The other 90 percent have normal, age-appropriate brain function. But we’ve already learned that about a third of the people in this cognitively normal group have significant levels of plaques in their brain. Therefore, according to this new expanded definition, they have preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. The authors are essentially arguing that we should increase our estimates of the total number of cases of Alzheimer’s disease by threefold. Worse still, the authors are making this recommendation despite the fact that there are reasonable doubts as to whether or not amyloid causes Alzheimer’s disease. Ah, you may say, but aren’t those doubts just the rantings of a few crazed misfits at the fringes of the field? Not really. We just read about these same doubts in the first two papers in the series.

The authors of the third paper understood that they were redefining Alzheimer’s disease, and they were clearly conflicted about what they were doing. In the final paragraph they admit, “The definitive studies … are likely to take more than a decade to fully accomplish.” Said in plain language, we have this idea, but we don’t have the data to back it up. Still, we are going to go with our gut, upend both basic and clinical research, and you’re going to have to live with it because most of your grant money comes from the NIA and the Alzheimer’s Association and their names are on this paper.

This is a huge problem because the definition of a disease is one of its most important attributes. Without a precise and accurate definition, there is no way to find a cure for any disease. Sadly, throughout the long history of Alzheimer’s disease research, strategy and politics have overruled science in the push to apply the label of Alzheimer’s disease to an ever-larger fraction of age-related cognitive decline and aging. As a result, we are left with basically no definition — or at least none of any value. Being in this situation, we are effectively blocked from making any real progress toward treatment. For proof of this, one needs to look no further than the unbroken string of expensive clinical trial failures. Our political calculus has overruled our common sense and caused us to stop listening to our own data — a clear example of how not to study a disease.

Karl Herrup is Professor of Neurobiology and an Investigator in the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. He is the author of “How Not to Study a Disease: The Story of Alzheimer’s,” from which this article is adapted.