When in Doubt, Copy

From infancy, we learn by copying others. It’s also how we navigate uncertainty throughout our lives. As the Delta variant of Covid-19 surges, for example, you may have seen an uptick of people wearing masks again at your grocery store, even when it’s not required. If this caused you to start wearing yours again, you’ve likely reduced your risk of hospitalization with no more thought than “I’ll do what she’s doing.” But such copying is a double-edged sword. You may be in a community where most people do the opposite, so you’re copying behavior that increases your risk.

The same goes for buying recent “meme” stocks — is GameStop stock a good bet? Sure, until it isn’t. You may recall in 2008, CNBC stock market analyst Jim Cramer shouted his infamous recommendation into the TV camera: “No, no, no! Bear Stearns is fine! Don’t move your money from Bear!” Soon afterward, Bear Stearns went belly up. A lot of people made fun of Cramer, including Cramer himself, who apologized profusely to his (former) fans who lost millions.

Cramer endured a period as a great piñata, and the Bear Stearns prediction was quite a gaffe, but that particular one was cherry-picked from the total number of predictions he ever made. What about all the ones that didn’t turn out so bad?

The financial meltdown that started in the last half of 2007 and reached epic proportions by late 2008 seems now as if it should have been predicted by anyone who looked at the asset sheets. It was, unlike the crash caused by the pandemic in March 2020, not tied to a clear event. Except perhaps to a few insiders, Bear Stearns was unpredictable as the specific grain of sand that would ultimately trigger the avalanche. Pundits who live on hindsight write as if they could have predicted the financial crisis if they had just had all the information. But they’re probably wrong.

Unpredictability extends far beyond the financial marketplace, of course. It is the essence of biological evolution. “Which groups will ultimately prevail,” Darwin wrote in the Origin, “no man can predict; for we well know that many groups, formerly most extensively developed, have now become extinct.” And as the late paleontologist Stephen J. Gould mused in his seminal book “Wonderful Life,” if we re-run the tape of life, the general effect is the same, but the exact specifics are different and unpredictable. The biological world, then, parallels the marketplace. Which species live and which ones die, or which companies weather a financial downturn and which ones fail and trigger massive securities sell-offs, can’t really be predicted. It’s why Cramer’s advice has been, statistically, about as reliable as a coin toss. We might make educated guesses, but over the long haul we’ll probably do no better than throwing darts and picking our winners and losers that way.

To see how easily interaction can undo prediction, consider something we normally think of as predictable, such as orbits of the planets in the sky. In the early 17th century, Johannes Kepler derived equations to predict the motions of two bodies in orbit around each other — Earth and its moon, for example — but as is well known to undergraduate physics students, a problem with three or more bodies — the Sun and all its planets — is not exactly solvable. Astronomers can update the locations of the bodies, and then predict incrementally where they will go next, but they can never predict their motions indefinitely with one overarching equation.

For understanding human social behavior, thinking in terms of two-player games can give us plenty of insights, but how real are these games in terms of what happens in life? Just as the orbits of three planets lack the determinism of two orbits, games with three players are quite different from those with only two. Let’s look at a couple of real-world examples with multiple players, not in an attempt to discover some deep governing laws — there aren’t any — but to look briefly at the dynamics involved.

Extending the Game

Most of us know about the Brexit vote of 2016 and, if you are British, you’re utterly sick of the subject and likely suffered the societal turmoil that has followed it. But Brexit didn’t start in 2016. Before David Cameron called for the Brexit referendum, which he calls his “greatest regret” from his time as Prime Minister, one could not have predicted the outcome of the 2010 parliamentary elections in the U.K., in which no party received a majority of votes. On election night there were standing not two but three viable candidates for prime minister — Liberal Democrat candidate Nick Clegg, Labour candidate Gordon Brown, and Mr. Cameron, the Conservative candidate. As the Conservatives were 20 seats short of a majority, they needed a partner to form a government. This was a three-body problem in a system accustomed to two-body problems. As it turned out, sentiment against the Labour party, which had been in power since 1997, was widespread, and Cameron received Clegg’s support and formed the first coalition government since 1974.

Similarly, in the United States the three-person basketball game of Hustle, in which each player tries to score as much as possible against his two opponents, is more complex than one-on-one basketball. Hustle has natural trade-offs between defending the player with the ball and letting the third player do that, while you (pretending to defend) wait for the rebound and try and score. In any multiplayer game, it often pays to let others make their move first, then copy their successes and avoid repeating their failures, a strategy that extends to politics and academia.

What often matters is not which thing is better but who else is using the thing — sometimes, even if that thing is worse for you.

Real life, however, is not a three-person game, or even a four-person game, and prediction becomes ever more a pipe dream. Our encounters with others are now arenas in which countless all-against-all games are being played at once. Millions of people try to make their own ideas more popular than yours. Countless ideas compete against each other for our attention, each following a seemingly different path toward hoped-for success in the marketplace. Some ideas may be bright green, some very interesting, some comfortable, some sexy, but most fail to become popular. The few that do become popular often succeed through a run of dumb luck.

Long Tails

Almost 20 years ago, Chris Anderson labeled this endless diversity of choice the “long-tail market,” where a few blockbuster ideas are by far the most popular and the vast majority of competitors are out there in the long tail. Anderson’s illustrative example is book sales on Amazon, where a few of the top bestsellers can outsell all others — millions of books — farther out in the long tail. The number-one idea may be, say, four times as popular as the number-two idea and nine times as popular as the number-three idea, and so on.

There are so many choices in the long tail — think of the millions of Amazon titles or possible music downloads — that Anderson, even before Facebook was born, argued for a whole new market philosophy that has become commonplace today: Don’t stake it all on a few blockbuster titles, but spread the risk across the endless variety of low-volume choices through free, online distribution. In this long-tail world, conditions change rapidly and information is incomplete. So many competing, similar options exist in the long tail that cost-benefit evaluation has very little to grab on to — thousands of social influences per day amid billions of social media users, tens of thousands of discernible topics, and thousands of daily decisions, including hundreds on food alone.

In some ways, this multitude of choices is not necessarily a problem for us. It’s not like we are prehistoric people choosing a crucial hunting or fishing strategy, where a wrong choice could lead to death. Quite the opposite; the long-tail market is one of unprecedented frivolity: what podcast to listen to, what to retweet, or what buzzwords to use.

In the 1960s and 1970s, marketing scientist Andrew Ehrenberg radically maintained that there was no such thing as dependable consumer loyalty, and that advertising could rarely be a strong force in how people made decisions. By analyzing sales data directly, Ehrenberg and colleagues developed a model — termed a “Dirichlet,” after the 19th-century German mathematician — in which consumers made choices based on merely chance and availability. If we add to this the newer realizations about social learning, we have the basic canvas against which more purposeful behavior would stand out.

A key distinction is recognizing the difference between the broader scale, where we select purposefully, and the finer scale, where one choice is about as good as another. It is better to eat than not to eat. That’s a broader-scale issue. And as long as you’re not diabetic, you can get away, at least in the short run, with subsisting on chocolate. What kind of chocolate to eat? That’s a finer-scale issue and not a very important one: Ecuadorian 77 percent dark or Pennsylvanian 76 percent dark? Just pick one; there’s no “wrong” answer.

What often matters is not which thing is better (for all practical purposes, they’re identical) but who else is using the thing — sometimes, even if that thing is worse for you. Classical economics would predict small risk, large benefit equals widespread vaccinations, for example. But that’s not what happened this year.

This likely occurs down to the level of buzzword choice. Your supervisor says we need to do this or that “going forward” (despite the redundancy, as this is what future tense is for), and later you start adding “going forward” to the ends of all your sentences in work-related meetings. Pretty soon you’re describing things happening “in real time” (despite that being the purpose of present tense). You probably copied these words subconsciously, with some bias towards when a supervisor or important work colleague uses the word. It doesn’t matter whether these superfluous words are helping people communicate. All that matters is that you made the subconscious connection from saying “going forward” to successful management.

Copycats

Copying is what people have always done because it’s not only easy, it’s effective. If it weren’t, we wouldn’t still be doing it because we wouldn’t be here. Our hominin ancestors, who we know were copycats par excellence, would have copied themselves out of existence if it were ineffective. The fact that humans live in groups and have heightened cognitive abilities ensures that copying has a revered place in our behavioral arsenal. Our ability to copy, and to do it so well, was one of the magnets that drew the three of us into studying the social arena in the first place. We think of our ancestors in East Africa two million years ago as being “primitive,” but it’s amazing to see the strong patterning in the stone tools they made. They all knew what the other guys were doing because they copied each other. Likewise, potters in Central Europe 7,000 years ago copied the designs on each other’s pots. Copying is so effective that all sorts of animals, even fishes, copy each other’s behavior in order to adapt. When real people rather than computers play games, they don’t doggedly follow tit-for-tat or some other mechanical algorithm. They copy other people’s winning strategies.

That said, it is striking how negative our culture can be about copying. Oscar Wilde — the paragon of the creative individualist — despaired of his run-of-the-mill peers when he observed, “most people’s lives are quotations from the lives of others.” It is much the same in behavioral science. Game theorists, for example, call copying “scrounging” or “eavesdropping.”

The take-home message was clear: Let others bear the risk of working out what to do, then copy those who succeed and act quickly, so you don’t fall behind other copiers.

As Nichola Raihani recounts in her 2021 book, our social instinct is a double-edged sword: Cooperation has led to greatest achievements, but conformity can bring out our worst. But we can often get by with something even simpler: Copy what is recent. Though increasingly sophisticated and granular, most social media algorithms today still favor information that is both recent and popular. The advantage of “copy recent” was shown in 2009 by our animal behaviorist colleague Kevin Laland and his team, who held a computer strategy tournament in which entrants played games against each other using algorithms that they could invent themselves or copy from others, or somewhere in between. The winners of the tournament, two graduate students who had never researched the topic before, used a simple algorithm that copied recent successful algorithms around them. Like MySpace, old success was just outdated information, and therefore discounted relative to more recent information. The take-home message was clear: Let others bear the risk of working out what to do, then copy those who succeed and act quickly, so you don’t fall behind other copiers.

In the 1990s, political scientists Robert Axelrod and Michael Cohen advised similarly in a business management book, “Harnessing Complexity”: Exploit what you’ve learned immediately, and move even faster if the environment is rapidly changing. Copying is pretty safe, too, since at least you will be doing something that has succeeded to the point of becoming visible to you. The easiest thing to do, even by accident, is to copy something popular and successful. In the social world, popularity is success, so you’ll be doing fine.

If we zoom out and focus on the population scale, we might be able to simplify how we categorize our options. We could simply distinguish directed copying, where people direct (or bias) their copying in some advantageous direction, from undirected copying, where people copy, perhaps subconsciously, without much knowledge about the person they are copying from. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Directed Copying

For many cases of directed copying, we can exploit traditional social diffusion models. These have people copying other people, but in many renditions the copying is directed at the behavior or object itself, not at any specific person. To use Kevin Laland’s term, these models are based on the “copy if better” rule. Classic diffusion models work best when the new option is a noticeable improvement, as often happens with technology, such as the bow and arrow of prehistoric North America or hybrid corn in the United States in the 1930s. If it is a better option, then once the choice finally arrives to you via someone else, you’re likely to adopt it, whether it’s a tractor over a horse-drawn plow or an iPhone over your old mobile phone.

Classic diffusion models often involve a binary choice: Something is either adopted or it is not. In the real world, however, we rarely deal with simple binary options, where one is better than the other. In cases of multiple equivalent options, spreading an idea is not like sending a wave through a placid pond. It is more like confronting a busy swimming pool full of splashing kids. Wherever you look, just about everyone is creating a small wave of his or her own. The pool is rough, dynamic, and unpredictable. How do you explain the spread of ideas through this pool, or the development of different, group-specific social norms?

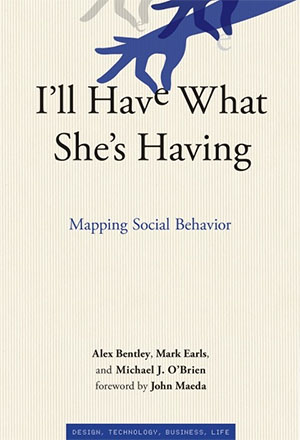

When confronted with a confusing array of seemingly equivalent options, another way to direct one’s copying is toward a particular person rather than trying to choose among all the different objects or behaviors themselves. As for whom we copy, there is a vast body of research on the topic, which we explore in our book “I’ll Have What She’s Having.” We may direct our attention toward prestigious people, people whom we’re related to, attractive people, people who are similar to us, popular people, older people, younger people, and so on. This has often been studied in traditional societies, in which kinship, status, and traditional forms of leadership and organization are essential components of influence.

Among these strategies of copying people, perhaps the most useful ones are directed toward people or groups that we’re trying to identify with. This is a form of conformity, which can lead to social diffusion within the limits of the group that is conforming. For example, a popular name diffuses through a generation, a dialect diffuses through an ethnic community, or a certain set of interlinked customs diffuses through a community claiming a common identity. In these cases, conformity directs the copying according to the rule of “copy the majority.”

The paradox of conformity, of course, is that we are all conformists in some way, and yet we do not all do the same thing — far from it. In fact, we find the greatest diversity of behaviors in places where people are the most densely packed together, such as New York, London, or Istanbul. One reason for this is that we seek different identities, and people like their distinctiveness, so they look for identity in small groups rather than in the masses. Instead of copying the masses, we might copy a known prestigious person. Others in our group will probably copy that same prestigious figure or get their cue from others locally that they should copy that person. In other words, we often seek to conform locally rather than globally. When conformity is directed locally, it might mean we adopt something only after enough of our friends or colleagues have adopted it.

Conversely, some people might conform according to a global threshold, such as choosing something they know is popular. A person might try to go with what he or she perceives as the most popular behavior at all times, or at least choose things predominantly from the top five, a rule that is quite easy to follow in today’s world of popularity lists for novels, music, and news stories. Even scientific articles are listed like this. A million people buying the number-one seller at Amazon is a very directed form of copying and a very rational form of copying. It is social learning at its most precise and selective.

Undirected Copying

The long-tail world of directed copying is a radical departure from traditional societies, not in terms of human nature but in terms of the massive intermingled diversity of choices and motivations for making them. There can just be far too many people to choose from, many as uninformed as you are, and a myriad of idiosyncratic reasons you might copy one person or another. In other words, there is not only an exhausting number of similar things to choose from, there can be far too many people, or even categories of people who look and act similarly, for us to know whom to copy, especially since they are probably copying others as well.

We might try to copy the successful, or the prestigious, but which ones, in a world where so many compete to portray these qualities, and not always honestly? Also, in a world where everyone competes socially and learns socially, our best strategies must change from one moment to the next. This again is the Red Queen effect applied to people: We need to run faster just to stay in one place, to keep changing just to stay competitive. For all those thousands of little choices we have to make every day — what shoes, what percentage cocoa in our dark chocolate, what viral news story to chat about using which buzzwords — maybe we can just pick someone, virtually anyone, to copy and save a lot of time. Besides, someone else’s choice will probably be perfectly acceptable. It works for them, after all.

We can call this undirected copying, and it probably applies more to the current world than it ever has, mainly because of choice overload. Many of us might copy in this manner quite unconsciously, or we may copy certain things quite carelessly. Undirected copying, however, can apply as a model even if each person has a specific reason for copying someone else, because at the population level there are so many different idiosyncratic reasons out there that we can consider it undirected.

Generally speaking, undirected copying refers to the population scale. It’s seeing the forest rather than the trees, or even more dynamically, like the pressure of air in a tire. Each air molecule has a very specific direction and speed at any given time. Do we care? No. All we care about is whether our tire has air in it. Similarly, when modeling collective behavior, we may be able to overlook all the idiosyncratic, personal reasons people give for their actions, especially if they wind up acting the same in the end.

We can try just assuming that undirected copying is the general rule and see what the model produces. If it matches real-world data, then an undirected-copying model can be used to predict rates of change as well as to distinguish between copying and other forms of social behavior. If it doesn’t match, this helps identify situations where there is some coherent direction of copying — people copying a particular person or a category of people or choosing something with some generally agreed-upon quality.

The undirected-copying model works like this: Take a number of individuals and lots of different ideas from which to choose. From one time interval to the next, most individuals choose their ideas by copying someone else. A small percentage (maybe 1 percent) of the pool of individuals, however, invents something new as opposed to copying an existing idea. Do this over and over, in a series of time steps. It’s that simple. If you like, one extra parameter that could be added is “memory,” that is, how far back in time someone can copy. In the model, a new idea usually doesn’t change much, but every once in a while a new idea becomes a big hit, all through the luck of copying.

Over the years, social media have made this model even more appropriate — people retweet memes without much thought, and now algorithmic bots retweet content regularly and sometimes at random. Compared to a decade ago, models of undirected copying are now more mainstream, as they can replicate all the population-scale patterns we have been discussing — long tails, continual flux, and unpredictability — that are ubiquitous on social media and in the “long tail” economy, where most new things fail but a few lucky ones are constantly becoming the new thing to be shared widely.

Lots of “rich-get-richer” mathematical models can produce long tails, but their major shortcoming is failing to produce change, or turnover, within the long tail — those with less can never overtake those with more. Undirected copying nicely produces this turnover; the more popular a variant is, the more likely it will be copied again, but this is not a fixed rule as in the rich-get-richer models. What sets undirected copying apart is the unpredictability and the continual flux, where the rich may get richer for a while but not forever. The top 40 (the exact number is immaterial) is in continual flux.

This resembles not only patterns on social media, with the constant rising and falling of new items on “most shared” lists that appear everywhere, but also in the historical lists of Fortune 500 companies, fashion popularity, product sales, and even English words including trendy academic buzzwords. This turnover is often remarkably regular. Among baby names in the United States, for example, there was a consistent average of about four new boys’ names and five girls’ names entering the respective top-100 lists each year, for nearly the entire 20th century. Even certain songs of birds show the same kinds of turnover. Chestnut-sided warblers of Massachusetts sing two kinds of songs — one for male courtship of females and the other for competition between males — that are transmitted between birds by learning. Over 20 years, male courtship tunes, under strong selection by females, hardly changed and do not fit the undirected-copying model. Females do not select male competition songs, which frees the males to make new songs out of the copied elements. The competition songs fit the undirected-copying model very well, with a long tail of popularity and continual turnover in the top ten.

In a certain niche of academic social science, the list of top-five favorite buzzwords turned over by an average of 20 percent a year for over a decade.

Academicians are sometimes like chirping birds. In a certain niche of academic social science, the list of top-five favorite buzzwords turned over by an average of 20 percent a year for over a decade. This means that about one buzzword a year is replaced by a new one in the popular academic lexicon. With undirected copying, turnover results from a balance of innovation, which introduces new ideas, and random drift, by which variation is lost through the luck of the draw. The more new ideas, the more they must compete with each other. The two balance out, and so adding more ideas does not necessarily change the turnover of the top 40. Equally counterintuitive, the turnover is fairly constant, no matter how many people are involved. So, for example, when we look at a trendy bandwagon idea in academic research, we see a continual turnover in the 10 most popular buzzwords associated with it, even though more and more scholars are jumping on the bandwagon.

How Are People Copying?

Many people accustomed to more traditional ways of thinking find this kind of rugged, ever-changing landscape, which is so typical of the long-tail world, difficult to navigate. Considering our models of directed versus undirected copying, here are three strategies for helping to make sense of things:

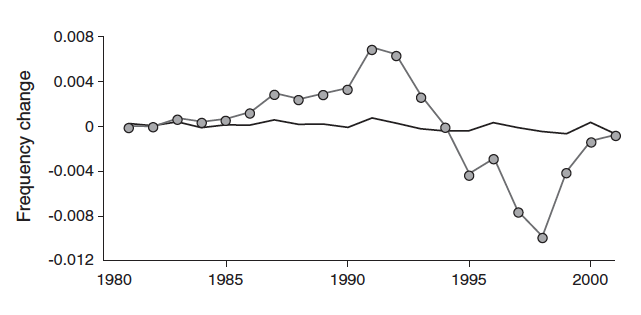

1. Identify what stands out against the background. Undirected copying is often all we can infer at the population scale, but if we zoom in, we can delineate more coherent directions of copying as meaningful departures from the undirected-copying model, as they stand out against it. These can often be seen quite clearly along the lines of variation, flux, and interconnections. In one study, undirected copying served as the background against which to fit data on dog breed popularity in the 20th century. Notice in the figure below the rapid rise and fall of dalmatians (filled circles) that is clearly visible after 1984. The reason for this rise undoubtedly is tied to the re-release of the Disney movie “101 Dalmatians.” What enabled the rise in dalmatians to be identified as a case of directed copying was the null model of undirected copying to test it against, represented in the figure by the continuous line. Directed copying changes the element of flux.

If directed copying is identified against the background, we can apply social diffusion models, in which popularity changes smoothly, typically in an S-shaped curve (but sometimes in an r-shaped curve). If an idea becomes generally perceived as better than all others, “copy if better” strategy brings it smoothly into the top 40, where it remains until something better comes along. As long as copying is directed toward the quality of ideas, then more people means more good ideas can be discovered, selected, and retained by the population. This was the basis for an argument in our book, where we contend that the origin of modern human culture was a result of more people, not necessarily of smarter people. This is also why gatherings of people can sometimes lead to rapid insight, because ideas are selected from the group and fed back to the group to build upon.

2. Focus on the interaction among the agents in your population. In democratic societies, it often is considered ideal to direct people’s choices toward the qualities of the options (“copy if better”) rather than to other people (“copy the majority”). The privacy of the ballot box is one example, where we hope candidates will be considered objectively (some countries even ban opinion and exit polls during the final stages of elections). We also want to make sure that investment decisions are directed toward the value of those investments and not toward the majority activity, which might be panicked selling, or in an undirected manner, which could point toward behavior even more irrational.

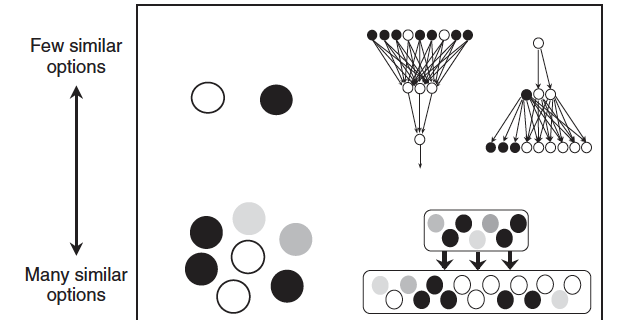

The directedness of decision-making at the population level can be altered through interconnections, as certain network structures amplify different patterns of copying. In the figure that follows, adapted from the work of Erez Lieberman and colleagues at Harvard, the two networks on the left favor undirected copying, whereas the two on the right favor directed copying. If we want people to generally follow the “copy if better” rule, hoping that quality gets selected, we might promote the networks on the left. The ideas adopted by the agents on the left are greatly dependent on the agent or agents upstream. This is like the classic marketing model of a few inventors who feed truly novel ideas to the early adopters, who then make things fashionable for everyone else. In any case, if we can characterize the kind of network, we will have an edge in understanding whether or not the system promotes the innovation of better ideas.

3. Learn to predict and cope with turnover. When all else fails, you can just try better methods of coping with flux and unpredictability. Models of conformity predict little turnover punctuated by massive cascades of change, whereas the undirected-copying model predicts popularity changes fairly continuously. When copying is directed, more innovators probably mean faster change, but if it is undirected, there must be more innovators per capita for turnover to accelerate. If copying is directed toward quality — copying people with true ability or things that are truly better — then there is an evolution toward higher quality.

So what does all of this tell us? It tells us, basically, that undirected copying is often an excellent, population-scale model for our modern long-tail distributions, where flux and unpredictability are often inevitable, no matter how much information we collect. We have as much chance at predicting the next meme stock now as Jim Cramer had in predicting Bear Stearns in 2008. Not only is the financial market a tangled web, saturated with hidden interconnections, but the interconnections are constantly evolving as well.

If ideas are essentially copied in an undirected manner, it’s better to accept unpredictability and to invest in probabilities, as an insurance company (or gambler) would, rather than expect to predict where things will lead. Like winds or the weather, social behavior is something we can gauge and adapt to, rather than control. Much of the time, “what she’s having” is a great bet.

Alex Bentley is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Mark Earls is an award-winning writer and consultant on human behavior, contemporary communications, and behavior change. Michael J. O’Brien is Provost and Professor of History at Texas A&M University. Bentley, Earls, and O’Brien are the authors of, among other books, “I’ll Have What She’s Having,” from which this article is adapted.