In Praise of Voice

In February, audio streaming giant Spotify purchased the podcasting company Gimlet Media for a reported $230 million. Dropped into a blog post published by Spotify’s CEO Daniel Ek was a fact he knew would be the only explanation his investors needed: “Our podcast users spend almost twice the time on the platform.” In a culture where time and attention are precious commodities, doubling users’ time on a platform is like doubling the coal holdings for a 19th-century robber baron; Ek could not have justified his interest in podcasts any more succinctly.

But a question remains: Why are we, the listeners, so drawn to them? Podcasts would seem to be the opposite of what we ask of media these days: they’re long, and they take not only time but attention to follow. As a result, they’re terrible for multitasking. Nor are they easily quotable or sharable on social media — there’s no screen grab to post, no gif to produce. Digitally speaking, podcasts are unwieldy, and generally consumed in private.

It’s tempting to think that it’s precisely this frustration of current media habits that makes podcasts so appealing. There are so many other ways we might resist the speed and brevity of our current media environment, however; unplugging, for example. Taking a walk in the woods. Sitting in a café without a laptop or phone. And there’s no surge happening for any of this behavior, so far as I can tell.

Instead, I think there’s something about podcasts that isn’t so much antithetical to other current media forms as it is complementary. And I think it can be found in the voice.

Our voices are, naturally, rich instruments. We hear so much in them: shades of meaning, tone, emotion. These are instruments none of us need to study, though all of us learn fully. Without thinking, we wield our own voices, and our understanding of others’, with the utmost skill.

Podcasting puts those skills on display. Think of Ira Glass, the host and creator of This American Life. We know him through his voice — and yet we feel like we know him, like really well (to use one of his characteristic locutions). Radio transformed the 20th century by bringing voices close to listeners’ ears; public personalities suddenly seemed more within reach, more familiar, more real than they had before. This phenomenon was put to use by both entertainment and, famously, propaganda. World War II was a battle of radio voices, as well as ideology and armaments.

Today, we use podcasting, simply, to listen to one another talk. It’s becoming an increasingly popular medium because the voices we hear on podcasts are heard more fully than in much of our other digital media. It’s why even Spotify, who already has all the music it could possibly want on its platform, now wants in too.

Without thinking, we wield our own voices, and our understanding of others’, with the utmost skill.

Consider the cell phone, a digital vocal tool we are all using constantly. Now that our phone network and tools are digital, few of us are “hanging on the telephone” the way we did when Blondie sang about the old analog system. Cell phone voices are digitally processed: compressed into small blocks of information that can be more easily shared over data networks, manipulated so that the words they convey are separated from any noise that surrounds them, encoded and decoded to ensure that those words are intelligible even in environments hostile to audio communication like moving cars or loud streetscapes. The result is tremendously efficient, but not very pleasant. Does anyone use the cell phone just for the pleasure of hearing someone’s voice?

Vocal music is not immune to this same kind of digital manipulation, though for different reasons. In the current musical climate, computers are the basis for recording; which means that all sounds in music must be digitized. There’s no need to additionally process sounds as they are digitized, as there is over a cell phone network — but it’s very, very easy to do so. And so we do. Voices in digitally produced music are routinely manipulated in ways that they never were in analog recording, partly because it was simply hard to do so previously; pitch is now altered, tone is altered, rhythm is altered, and the natural sounds that surround a singing voice including breath are routinely deleted.

The fullness of a voice as we learn to hear it, from the womb forward, is altered by the digital environment for telephones and recorded music. But radio has remained largely immune to these new tools. Live radio doesn’t employ the manipulation of the digital recording studio, for practical reasons. And recorded radio — the type of shows that are produced for later airing and that have adapted so well to podcasting — has generally stayed away from manipulating the voice, even as it freely uses digital tools for other purposes, like the elaborately produced soundscapes of Radio Lab.

Podcasting, in other words, by leaving the voice relatively unmanipulated, now stands out in our digital media environment. When else, you might ask yourself, do you listen to a voice as carefully as you do on a podcast? Only IRL, as we say.

Which I believe explains why even in this hypermedia environment, so many of us are willing to focus on one extended narrative — as long as it’s in the relatively unmanipulated vocal format of podcasting. Voices say so much to us. But only when we let them be heard fully.

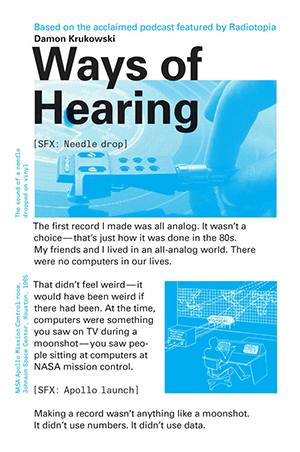

Damon Krukowski is a musician (Damon & Naomi, Galaxie 500), poet, publisher, and author of “Ways of Hearing,” a book based on his six-part podcast produced for the public radio podcast network Radiotopia.