The Quiet Power of Reflective Games

A big-eyed, wee creature stands in the hand of a giant king. “All I ask of you is to wait,” the king says, “and never to leave these caves.” He will sleep for 400 days, and the creature, called just “the Shade,” is tasked with waking him up after that time. Fade to the Shade’s house deep within the cave system. A countdown starts running in real time: 399:23:59:59. “So, this is my home,” the Shade tells us, “A nice place to spend the next 400 days waiting.” We take control of him with no other task than to pass the time. Would you read books, decorate the Shade’s chamber, explore the caves, even dare to try and venture outside them? The game will not push you in any direction. The Shade walks very slowly, and the countdown is so long that instead of adding pressure to the gameplay, it becomes an abstraction. This is “The Longing.”

“The Longing” (Studio Seufz, 2020) is a slow game, not because of technological limitations or some faults in its design. It is intentionally slow — so much so that the whole experience would not make sense with a different pace. It aspires to be a transcendental game experience. Paul Schrader explains his idea of the transcendental style in film by referring to “dead time,” the time normally edited out. In transcendental style, dead time is not an accident but a technique. The aim is to put the viewer in a state of reflection (deep thought) and reflexivity (examination). Equally, the use of time in “The Longing” allows for slow, uninterrupted thought.

“The Longing” is not an exception, but it defies the dominant styles in the industry just by virtue of existing. Reflective games, no matter how common they are, are always perceived as anomalies, an opposition or reaction to what is normal. Once, when I was giving a talk on slow games, someone asked me if there are fast games. Perhaps we have not needed to name them because they are the default, and the vast history of games that do not fit that model has been conveniently pushed aside to maintain the narrative.

Trying to define and unify this reflective style is tricky. First of all, why not follow cinema and call the whole corpus “slow games”? Because that flag has already been waved in a very particular moment for a very particular subset of games and for very particular reasons. For example, text games in the 1980s did not have the same aesthetic and industrial aspirations as contemporary self-labeled slow games; more importantly, they have not been retroactively claimed by the movement’s defenders. One needs to bring them all together under a single name that respects differences and avoids confusion.

Calling them “relaxing games” does not help much, either. Yes, relaxation is important, but it is not the goal of a more melancholic, early reflective game like “Ihatovo Monogatari” (Hector, 1993) or a horror-tinted production like “Death Sranding” (Kojima Productions, 2019). And since video games are a form of leisure and entertainment, are they not in themselves a way to unwind? Philosopher Marshall McLuhan called games “extensions of the popular response to the workaday stress.” A commercial for the lightgun game “Time Crisis 2” (Namco, 1997) read, “Don’t just manage stress, blow its freaking head off.”

Reflective games, no matter how common they are, are always perceived as anomalies, an opposition or reaction to what is normal.

And following this, should we bring these games together based on how they are played? I believe not. Slow play is a fascinating phenomenon, but it can happen in games like the “Grand Theft Auto” series (Rockstar, 2001–2021). Studying players and communities is a commendable enterprise, but it is not my goal. Accordingly, slow play should not, in itself, be considered a defining trait of reflective games. Rather, I believe works should be cataloged according to what they set out to do. “Horror” is a work made to elicit horror, whether or not it actually succeeds, and reflective games should be conceptualized around a common aim.

I believe this aim manifests in structures that can be formally analyzed, regardless of reception or the act of gameplay. To this end, I will summarize and unpack the constitutive elements of reflective games in six points that should give us a clearer picture of what we are dealing with — and what we are not.

1. Reflective games demand a particular type of attention.

This is their necessary and sufficient condition. Since they intend to satisfy the need for reflective-playful thinking, they require us to use our slow mode of thought. They need sustained, unbroken attention, ignoring all surrounding distractions, and they need us to allow this attention to expand, wander, and ramble. A fast and demanding game such as “Dance Dance Revolution” (Konami, 1998) activates a fast mode of thought that is laser-focused on the task at hand, ignoring distractions as much as reflective games do, but with no room for reflection or reflexivity. Even in tense environments and situations, as in mysteries, horror, and tragedies, reflective games allow us to ponder over what we are doing. They fuel and are fueled by duration, uninterrupted, and undistracted thought.

2. Reflective games use time as a technique.

This characteristic creates the necessary conditions for the previous point. Reflective games dilate time, let it flow uninterrupted, and often ask the player to go through detailed routines and rituals. To achieve this, they usually exploit repetition, which is already a central element of games. And they demand patience. Consider “Neko Atsume: Kitty Collector” (Hit-Point, 2014), an idle smartphone game in which we wait for cats to visit us, build their trust bit by bit, and take care of them. Time, especially dead time, is the foundation of reflective games. It is becoming more common to see slowness in parts of mainstream games, such as “Red Dead Redemption 2” (Rockstar Games, 2018). In those cases, one may doubt whether they are fully reflective or hybrid in their modes of play.

Dead time in reflective games is not a pause, a breather, or a moment of respite between action; rather, it is the center of the game.

To understand this, we need to acknowledge that video games can feature different chronotopes — or combinations of setting (time and space) and action — that alternate in their structures. Reflective chronotopes are becoming common in what are otherwise action games. Dead time can tint an experience or define it; the fuzzy border, if there is one, lies in the core gameplay loop. Dead time in reflective games is not a pause, a breather, or a moment of respite between action; rather, it is the center of the game. For example, the experimental blockbuster “Death Stranding” — in which we control a porter carrying supplies in a postapocalyptic United States — has enemy encounters and boss fights, but they punctuate an otherwise laborious delivery simulator. There is no traditional fast travel in “Death Stranding” because the time and effort that it takes to go from one place to another is the gameplay.

3. Reflective games are designed to minimize gameplay pressure.

Traditional game design elements, such as goals, time limits, game-over conditions, or life bars, are downplayed or entirely ignored. These are elements of pressure. They may function as actual hurdles, such as enemies, puzzles, time limits, or the constantly decreasing health bar of games such as “Gauntlet” (Atari Games, 1985) and “Wonder Boy” (Escape, 1986), or as flourishes to stimulate the player. Flourishes may be intense music in a boss fight, the fake permadeath warning in “Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice” (Ninja Theory, 2017), a character repeatedly asking us to move forward, or haptic feedback in horror games. In all cases, these elements are meant to put players in a state of alertness and remind them that the game can end.

Philosopher Bernard Suits theorized that a game is voluntarily overcoming unnecessary obstacles, and elements of pressure build on that lusory pact. Their absence signals a different relationship with play. And without them, the potential for vertigo is virtually gone; at best, thrills are replaced by dread or the feeling of the sublime. Consider the tile-matching game, “Pick Pack Pup” (Nic Magnier, Arthur Hamer, Logan Gabriel, 2021), which includes a Chill mode that removes the penalties and the end conditions; or “Pullfrog Playdate Deluxe” (Amano, 2024), which tells us that its Zen mode is “for those that just want to chill.” Reflective games do not make away with failure, but they focus on other parts of play and playfulness.

4. Reflective games are designed to favor elements of meditation.

Pressure creates tension, and we need an operative word to describe its opposite in game design. One could be tempted to call this “relief,” but relief depends on tension, and the kind of creative elements that I am trying to bring forward here can exist on their own. Moreover, they enhance the game experience. These are elements that create a sense of ease, but are not exclusively about a lack of traditional difficulty. They are not fully elements of “calmness,” either. Again, calmness is what we get in the absence of pressure, but we need a vocabulary to describe the presence of elements that make room for thought to breathe. Devices such as slow pace, aimlessness, and mechanics that encourage pause (for example, sitting down) belong in this category, which we might call meditativeness. They ask us to do very little, avoid overstimulation, and also expect us to observe everything carefully. Reflective games are not passive, but their activities are less hurried and expand beyond the vocabulary of winning and losing.

5. Reflective games have a complicated relationship with flow.

Losing oneself in a game, getting into “the zone,” becoming entranced: If you play video games, you are very likely familiar with expressions such as these. All of them have to do with flow, the deep engagement with an activity studied by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and accepted in game studies and games criticism for a long time, almost like an axiom. Arcade games were discussed in their early days in these terms (sometimes, to add more confusion to reflective games, using the word “Zen”); they were enthralling, captivating, hypnotic. Flow was the central concept in Jenova Chen’s early works, with “flOw” (Thatgamecompany, 2006) being a companion piece to a thesis exploring it. More recently, “Tetris Effect” (Enhance Games, 2018), which started development as “Zen Tetris” (see how the terms are mixed up all the time?), allows us to fill a “Zone” bar and activate it to carry out masterful moves.

The flow channel, or the space between boredom and frustration, is a standard in game design for fine-tuning difficulty. Games are sometimes even criticized for not featuring what the reviewers deem optimal flow channels. But we can argue that flow is in itself insufficient to understand games and, more especially, reflective games: It is built on challenge and action, on an uninterrupted experience, while fragmentation, stuckness, and interruption can be positive elements of game design.

They ask us to do very little, avoid overstimulation, and also expect us to observe everything carefully.

6. Reflective games are designed to favor catalysts.

Umberto Eco wrote about the delectatio morosa, or the pleasure of slowing down and focusing on the unimportant. In his structural analysis of narrative, Roland Barthes distinguished between nuclei, or cardinal functions, and catalysts, which are moments irrelevant to action. This distinction is not based on the intensity of action or on pacing but on the possibilities of the events. A nucleus is not only a moment that advances the story but one that deals with causes and consequences, with alternatives at play. Catalysts (or catalyses), on the contrary, are moments of stasis, when the state of the world does not change much, and our actions are of little consequence. Catalysts give the fictional world verisimilitude and texture — they bring it to life.

In “Coffee Talk” (Toge Productions, 2020), we slowly unravel the stories of the patrons of a coffee shop, and very little happens around that. “The Stillness of the Wind” (Lambic Studios, 2019) takes place at a farm, but its simple farming mechanics are not even the main point: Routine is. In the idle games that truly exploit waiting, these waiting periods structure their whole experience.

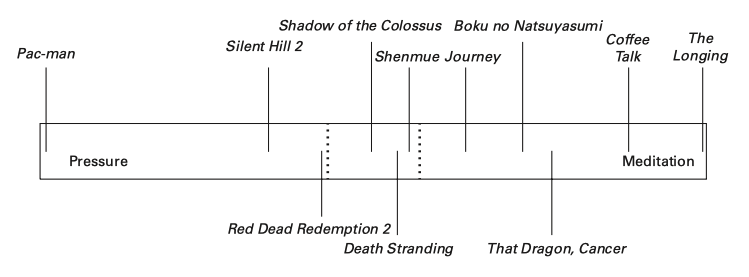

Reflective games do not always give us clear delimitations in the way the “Zen” and “slow” labels do. Pressure and meditation, in the analytical model below, lie on the same spectrum, and games can move toward the pressure end quite a bit before they stop being reflective.

Consider some borderline cases, such as survival terror “Silent Hill 2” (Team Silent, Konami, 2001). It shares many elements with horror graphic adventures, and graphic adventures are usually reflective. Some graphic adventures, such as the “Space Quest” series (Sierra On-Line, 1986–1995), feature a strong element of pressure: death. Others do not. All horror graphic adventures, such as “Phantasmagoria” (Sierra On-Line, 1995) or “Dark Seed” (Cyberdreams, 1992), depend on an aesthetic element of pressure: dread. But dread requires slowness, build-up, and dead time. It needs to prolong an unpleasant situation to its breaking point and beyond. “Silent Hill 2” includes some action (which at moments feels almost mandatory, a toll of its time and genre), but that action punctuates an experience of wandering, slow exploration, and puzzles. Action is not its main chronotope. “Silent Hill 2” trades jump scares for a dead time of anxiety. We even get warned of approaching enemies by the distressful buzz of our radio.

The further a game drifts from models of action and pressure, the clearer the reflective style becomes. The cutoff point is not an actual point but a gray zone. The history of reflective games, as we will see, is the history of inching toward the meditative end and gaining awareness of its stylistic potential —and this awareness has led to many names and strategies. This inclination of reflective games toward meditation instead of pressure makes it easier to create certain ludonarratives, and so they tend to replace power fantasies with abstraction and contemplation. “Quiet as a Stone” (Richard Whitelock, 2018) is a game about building nature dioramas with no conflict. “Slow Living with Princess” (Kadokawa, Tsukurite, 2023) is about a failed hero who retires to the countryside to live as an apothecarist. While challenge, leveling up, and empowerment can coexist with reflection, this style is a better fit for other experiences and themes. Apocalyptic battles are hard to render here. This is a comfortable home for the everyday, the intimate, the failed, and the frail.

Víctor Navarro-Remesal is a media scholar specializing in games working at TecnoCampus, Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain. He is the editor of the book series “Ludografías” (Shangrila), the current president and one of the founding members of DIGRA Spain, and the co-president of the History of Games conference. He is the coeditor of books such as “Perspectives on the European Videogame” and the author of “Zen and Slow Games,” from which this article is adapted. An open access edition of the book is freely available for download here.