What’s Wrong With Innovation?

For more than half a century, innovation was celebrated as a universal good. That consensus has now cracked. While the imperative to innovate continues to drive change worldwide, critics increasingly depict innovation culture as a source of inequality or accuse its champions of woke groupthink. What changed?

My book “Every American an Innovator,” from which the following article is adapted, tells the story of how experts spread the gospel of innovation — from the cornfields of 1940s Iowa to Silicon Valley tech giants today — transforming the lives of nearly every American in the process. In the following text, adapted from the chapter “Innovators on Trial,” I chronicle the moment the innovation consensus shattered. The entire chapter and an open access edition of the entire book are freely available for download here.

At the dawn of the 21st century, the watchword “innovation” seemed to capture the life-force of the United States. Despite the dot-com bust, the relentless pace of technological change was undeniable.

By the early 2000s, a vast majority of Americans had access to the internet, which in turn facilitated innovations in mobile computing and social media. Just five years after the Apple iPhone hit the market, two-thirds of Americans owned a smartphone while Facebook grew from a few hundred Ivy League students to over a billion users.

Like automobility, electricity, and computing in eras past, the smartphone and social networks came with a magical aura — a tactile merger of technology and culture in the palm of your hand, making all the world your friend. Unlike the utopianism of the 1950s, these transformations were not attributed to the inevitable march of technology. Rather, journalists, politicians, academics, and PR specialists linked these breakthroughs to an innovation culture that unified technological, economic, social, and political change.

Exuberance for innovation spanned partisan lines but was especially embraced on the left. The New Yorker, for example, was a leading innovation booster. Its inaugural 2007 “Innovators Issue” profiled scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, the graffiti artist Banksy, the architects of New York City’s High Line urban park, and billionaire Richard Branson’s foray into biofuels. Staff writer Malcolm Gladwell, meanwhile, became an innovation guru for the masses.

Innovators were the heroes of the new millennium. A cottage industry of memoirs and business histories celebrated billionaire founders, from Nike’s Phil Knight to Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Tesla’s Elon Musk. The digital entertainment industry championed artistic creativity, lauding the animator–entrepreneurs of Pixar and hip-hop mogul Dr. Dre, who invested in an arts-based innovator academy. The reality show Shark Tank played its part by turning pitch meetings into household entertainment, spotlighting entrepreneurs from all walks of American life.

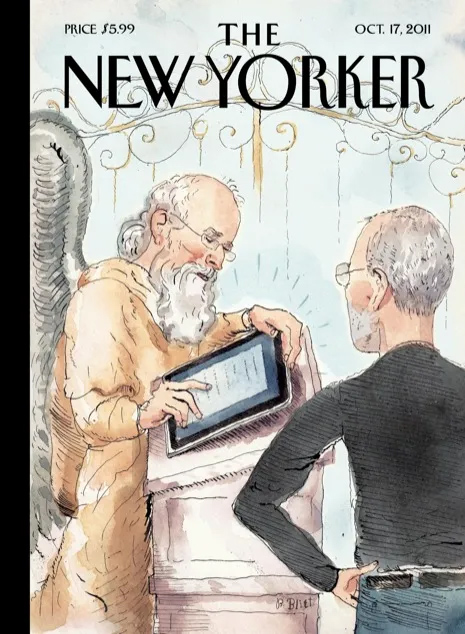

Steve Jobs became the national archetype of innovation, proving it wasn’t just for the young or limited to technology and business. After his untimely death from pancreatic cancer, he was enshrined as the greatest innovator of his era. The New Yorker lovingly canonized him at heaven’s gate, with St. Peter searching the Book of Life on an iPad, while Walter Isaacson, former president and CEO of the Aspen Institute, published a biography just two weeks later, declaring Jobs “a magician genius” who “combin[ed] the power of poetry and processors.”

Barack Obama’s presidency was as crucial to this innovation triumphalism as Silicon Valley’s cultural and economic dominance. His 2009 Inaugural Address championed “the risk-takers, the doers, the makers of things” as drivers of American history. Technology journalists reinforced this charismatic image, labeling him the “entrepreneur-in-chief” and “innovator-in-chief.” Indeed, innovation was central to Obama’s governing philosophy: His Strategy for American Innovation fused the technoeconomic blueprint of the 1980s with a focus on access and inclusion, and his cabinet and federal agencies were filled with interdisciplinary experts who moved back and forth between government and the high-tech sector.

The administration cultivated innovators at every life stage and launched programs at virtually every level, from expanding innovation awards to women and minorities to creating fellowships, innovation “boot camps,” and education initiatives designed to nurture innovators from K–12 to government labs.

Innovation expertise had grown into a diverse and widely practiced vocation. Think tanks proffered their own models, such as the Brookings Institution’s blueprints for “Innovation Districts” distributed to municipalities nationwide. Universities, high schools, and even elementary schools developed innovation and entrepreneurship programs that reached thousands of students. A new generation of innovation experts came to prominence. Start-up founders and community activists alike argued that every stale and oppressive element of the status quo stood to be positively disrupted.

Then came the backlash.

Techlash

The growth of innovation culture was the result of a decades-long persuasion process during which its evangelists encountered only limited resistance. In the 1970s, for example, scientists had criticized the National Science Foundation (NSF)’s innovation programs, arguing that the government should stay away from commercialization and stick to fundamental research. Engineering professors likewise had dismissed entrepreneurship education as a marginal activity. Technology journalists had developed the trope of technology entrepreneurs as socially awkward nerds and geeks. In the 1980s and 1990s, the occasional skeptical economist challenged the long-term benefits of regional innovation schemes. After the 2000 dot-com crash, business insiders and late-night television hosts ridiculed misbegotten ideas like Pets.com. On the whole, however, innovation culture amassed power and support.

The growth of innovation culture was the result of a decades-long persuasion process during which its evangelists encountered only limited resistance.

In the early 2010s, innovation culture experienced its first sustained challengers. In 2011, the same year that the NSF released its strategic plan “Empowering the Nation Through Discovery and Innovation” and Isaacson published his bestselling biography of Steve Jobs, a set of influential books criticized the “privatization” of science, the “delusion” of technology fixes to societal problems, and the “corrosive” psychological and social impacts of entrepreneurial work. The Oscar-winning movie “The Social Network” meanwhile probed the dark side of innovators, dramatizing Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s rise to power.

Still, innovation skepticism remained a fringe position.

During President Obama’s second term, challenges to specific elements of innovation culture coalesced into a synthetic critique. Leftist intellectuals led the attack. In 2014, the New Republic’s Evgeny Morozov called innovation a “naive fetish” and pointed to the concept’s bipartisan support as an indicator of its vapidness. In 2015, technology historian Lee Vinsel cast himself as a digital-age Martin Luther in his biting essay “95 Theses on Innovation.” At the height of the 2016 presidential campaign, populist critic Thomas Frank excoriated liberalism’s “excessive hope” and called Obama a puppet of the “Innovation Class.” According to Frank, this “rapacious” cult rationalized capitalist inequality through its worship of “credentialed expertise,” meritocracy, and education as the basis of social change. A series of digital magazines including Baffler, Aeon, and Jacobin focused their critiques on innovation culture’s flawed ideology and its detrimental impacts on labor. Inside the academy, historian Benoît Godin established the journal NOvation for the growing specialty of “critical innovation studies.”

This innovation revolt was part of a broader Techlash that revived the antitechnology genre of the 1960s. The Techlash linked the digital order to surveillance, racism, environmental destruction, and the death of democracy. Scholars, investigative journalists, disenchanted technologists, and activists published hundreds of articles and dozens of books critical of innovation culture. Perhaps nowhere was this debate more prominent than on the social media platforms such as Twitter that the critics simultaneously used to gain a following and to target.

The entertainment industry also turned against innovation. The HBO satire Silicon Valley, for example, began in 2014 with a cast of nerdy down-on-their-luck innovators out to slay corporate giants; but as the series unfolded, it revealed innovation culture’s endemic rot and made the case that every participant was complicit. By the end of the 2010s, there was a thriving commercial market for docudramas that included The Social Dilemma, We Crashed, and at least four exposés on disgraced Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes.

As the country reached new levels of partisan rancor during the 2016 election, “Big Tech” became a shared epithet of the left and the right. Critics with opposing politics shared the same insults, comparing innovation culture to drugs and venereal disease.

Critics on the left sought to dismantle the monopolistic power of the “tech giants,” their tax avoidance, and inhumane working conditions. They also accused social media companies of putting profits over people, resulting in lax security and misinformation, which Russian actors exploited during the 2016 election. Rightwing politicians and pundits meanwhile railed against “woke capitalists” in innovation regions that had spread from California and Massachusetts into Texas, Colorado, Georgia, and other conservative states. They attacked the tech industry’s use of H1-B visas as a form of sweatshop labor and amnesty for immigration. The conservative media outlet The Federalist, for example, published over 500 articles on how “Big Tech Oligarchs” corrupted children, colluded with China, stifled competition, censored freedom of speech, hurt public health, and supported terrorism.

The Techlash also brought a dramatic reversal in representations of innovators. Popular media replaced glowing profiles of entrepreneurial heroes with takedowns of greedy and rapacious villains. There were lowlifes such as hedge fund “pharma-bro” Martin Shkreli, whose business model was to purchase out-of-patent drugs and raise their prices by as much as 5,000 percent. There were disgraced disrupters, like ride-sharing Uber cofounder and CEO Travis Kalanick who was forced to resign amid revelations of ethical violations and sexual harassment. There were frauds, like Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes, who The New Yorker had once praised for “democratizing healthcare” with her rapid and inexpensive blood tests but who had deceived patients and investors from the beginning. Finally, there were robber barons and supervillains — Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and Elon Musk — whose achievements were as undeniable as they were unavoidable. These billionaires had amassed so much wealth and power that they existed above the law and normal society.

What’s wrong with innovation?

After World War II, experts celebrated innovation as the answer to society’s biggest questions: how new ideas were created, how wealth emerged, and how the world could be changed. The Techlash challenged these pillars of the innovation consensus. Where innovation experts saw a harmonious synthesis of technology and culture, critics identified a destructive neoliberal order.

At the core of the innovation imperative was a belief in the society-changing power of digital technology. In the late 1950s, technology managers at Bell Laboratories promoted innovation to describe the blurring of science, technology, and society that had given rise to the transistor and, along with it, hybrid technoscientific careers. Engineers, entrepreneurs, and journalists carried this vision westward, portraying Silicon Valley as the leading edge of a decentralized, creativity-based future.

In contrast, anti-innovation experts in the 2010s argued that the relentless pursuit of digital technology had resulted in a misallocation of the nation’s talent. Critics argued that from kindergarten to college, the American education system overemphasized STEM careers at the expense of well-rounded citizens. Addictive social media networks brought record users and profits while the nation’s infrastructures crumbled. Designers built gadgets for the innovation class, while residents of Flint, Michigan, drank poisoned water.

Another promise of the innovation consensus was that its experts could accelerate the uptake of desirable social and technological changes. From Everett Rogers to Richard Florida, innovation experts offered models that capitalized on the relationship between ideas and social and material change.

Designers built gadgets for the innovation class, while residents of Flint, Michigan, drank poisoned water.

During the Techlash, however, critics accused these gurus of peddling a bankrupt ideology. The expert takedown became its own genre in which “delusion” became the newest buzzword. Urban theorists accused Florida of selling false hopes to struggling regions and normalizing the pathologies of booming cities. Science and technology studies scholars declared design-thinking to be an imperialist ideology. “Disruption” was the dirtiest term of all. In The New Yorker, historian Jill Lapore attacked her Harvard colleague Clayton Christensen, calling his vision of disruptive innovation a misguided “gospel.” The rhetoric of religious conflict was a common framing; innovation culture was a cult, its leaders were corrupt prophets, and its aspiring innovators were brainwashed disciples.

Another foundational claim of the consensus was that innovation was the driver of economic growth. Ever since economist Robert Solow had identified technical change as the secret to productivity, bureaucrats, corporate boosters, and politicians advocated for the right mix of regulatory reforms and government incentives to foster entrepreneurial activity, industrial policy, and regional clusters.

In the 2010s, a range of critics instead assailed innovation policy as an engine of inequality. Rather than a perpetual flourishing of start-ups, they claimed that the digital economy produced unregulated monopolies that throttled competition. The resulting concentration of wealth and power produced a stratified economy with billionaires at the top and an expanding service class at the bottom. Innovation hubs like San Francisco, Boston, Seattle, Austin, and Washington, DC, became playgrounds for the rich that were unaffordable for anyone else. Competition for talent in universities was fierce, resulting in a similar divide between winners and losers. However, despite 40 years of efforts to diversify the innovation economy, racial and gender discrimination persisted. These inequities at every level strained the credulity of claims that social and technological progress proceeded in harmony.

Critics further challenged the productivity gains ascribed to innovation. The economist Tyler Cowen made the case that the United States had reached a “great stagnation.” In “The Rise and Fall of American Growth,” economist Robert Gordon, a former student of Solow’s, added credibility to the argument, showing that the rate of overall innovation had been in decline since the 1970s. The conservative pundit Ross Douthat amplified the message, concluding that “21st-century growth and innovation are not at all what we were promised that they would be.”

Even innovation’s champions identified worrisome trends. In 2013, for example, MIT assembled a task force to revisit its Reagan-era Made in America project. The “Making in America” report documented the ongoing decline of manufacturing despite decades of public–private initiatives and lamented the persistence of regional inequality. “Our own initial lofty conceptions of innovation,” the MIT Commission concluded, had been “brought down to American earth.”

The final, unifying pillar of the innovation consensus was that its mindsets and methods were a path to civic renewal. Ever since the democratic experiments of John Gardner in the 1960s, experts had claimed that public–private alliances could change lives and build meaningful relationships. These programs focused on education reform and community development with the goal of extending innovation’s benefits to those previously excluded.

Critics of civic innovation, however, found dashed dreams and unfulfilled promises at every level. In 2017, after participating in a “progressive” project to create a public school for underserved students via a collaboration between educators and game designers, the anthropologist Christo Sims offered a scathing picture of failure. He argued that a fetish for technological solutions reinforced the status quo and that the “professional fixers” behind innovation-centric programs used a toxic form of idealism to ignore their failures while continuing to spend taxpayer money.

Stanford Social Innovation Review’s David V. Johnson similarly argued that the Obama administration’s courting of young technologists into government service created a “revolving door for our new Establishment.” At the global level, former management consultant Anand Giridharadas attacked philanthropic foundations as tools for burnishing the reputation of innovation culture’s corporate winners.

The general conclusion among critics was that innovation was, at best, a Pollyannaish strategy doomed to fail and, at worst, a deliberate strategy for maintaining the status quo.

Matthew Wisnioski is Professor of Science, Technology, and Society at Virginia Tech. He is the author of several books, including “Engineers for Change: Competing Visions of Technology in 1960s America” and “Every American an Innovator: How Innovation Became a Way of Life,” from which this article is adapted. An open access edition of the book is available for download here.