The Creativity Hack No One Told You About: Read the Obits

I’ve been reading the obituaries for as long as I can remember. At first glance, they might seem like little more than a collection of dates and accomplishments. But for me, they’ve become a wellspring of creativity — each one a glimpse into a life I never would’ve imagined. And as decades of creativity research suggest, the most original ideas often come from the most unlikely sources.

That’s why one popular piece of advice for boosting creativity is to learn something new every day. But here’s the catch: This only works if that new information is very different from what’s already in your head. This is where most of our modern habits fall short. Internet searches, for instance, give you information that’s related to what you already know, or information that you’re already interested in. So, how do you escape that loop and stumble upon something unexpected, something you didn’t even know to look for? The obituaries, obviously — but I’ll come back to that.

In February, I interviewed Yoed Kenett, who studies high-level cognition and creativity, for my podcast “The Science of Creativity.” His research shows that creativity thrives on making connections between very different concepts. The core idea is simple: Our ability to create relies on prior knowledge, and our creative potential increases when that knowledge is organized into conceptual networks that help us search for, connect, and generate new ideas — what Kenett calls a “Google of the mind.”

The greater the distance between two ideas, the more original and surprising their combination tends to be.

This research goes back to the 1960s, when psychologist Sarnoff Mednick was studying patterns of thought in people diagnosed with schizophrenia. He was exploring the idea that highly creative individuals might share certain associative patterns with those diagnosed with schizophrenia, namely, the tendency to make connections between seemingly unrelated ideas. In a classic 1962 experiment, Mednick asked participants to say the first word that came to mind when they heard a prompt like table. Less creative participants tended to respond with obvious associations like chair or leg. The more creative participants gave those answers, too, but they also came up with more surprising ones, like food or even mouse.

Mednick’s observations led him to propose that highly creative people have a different kind of memory structure — one that holds a wider range of ideas and forges more unexpected connections between them. He called his theory the associative theory of creativity. His research showed that creative ideas are more likely to emerge from combinations of concepts that are further apart in the mind’s conceptual network. The greater the distance between two ideas, the more original and surprising their combination tends to be. More recent research, by Kenett and others, confirms these observations.

Some of the best-known stories of invention come from unexpected associations. Velcro, for example, was invented when George de Mestral was walking his hairy sheepdog through a field of burr-covered plants. It’s notoriously difficult to remove burrs from an animal’s hair, which means the animal is going to carry seeds a far distance, allowing the plant to spread more successfully. De Mestral took out a magnifying glass and saw very tiny hooks that clung to the dog’s hair. Then he made the distant connection: The burr’s mechanism, designed by nature to spread seeds, could be used to make a clothing fastener. There’s no shortage of other surprising inventions that began with distant connections: Post-It notes, the X-ray, shatterproof glass, the microwave oven, silly putty, heart stents.

The psychologist Dedre Gentner also found that the more conceptually distant two ideas are, the more creative their combination tends to be. For instance, she found that if you ask 100 people to imagine a chair combined with a table — two closely related items — most of them will picture something like a school desk. It’s an obvious match within the category of furniture. But if you asked 100 people to imagine a chair combined with a pony — very distant concepts — the results are far more varied and surprising: A chair you sit on while grooming a pony, one that a pony sits in, one shaped like a pony’s head, or one covered in fur.

Gentner calls this property mapping — when people borrow attributes like texture or shape from one concept and apply them to another. It’s a kind of remote association, and clearly more creative than imagining a standard school desk. But Gentner identified something even more powerful: structure mapping. This happens when you transfer the relational structure of one concept to another. Say you combine “pony” and “chair” and picture a chair shaped like a pony — that’s still property mapping, just more elaborate. But if you imagine a small chair, you’ve made a bigger leap. That’s structure mapping: drawing on the idea that a pony is smaller than a horse, and applying that relationship to redefine the size of a chair. These kinds of mappings — especially when the underlying relations are abstract or non-obvious — tend to produce the most original and surprising combinations.

You can strengthen your ability to make remote associations by exposing yourself to a wider variety of information, especially from conceptually different domains. Most of us stick to what we know. We don’t normally encounter distant concepts in everyday life, so stretching our minds into unfamiliar territory takes some effort.

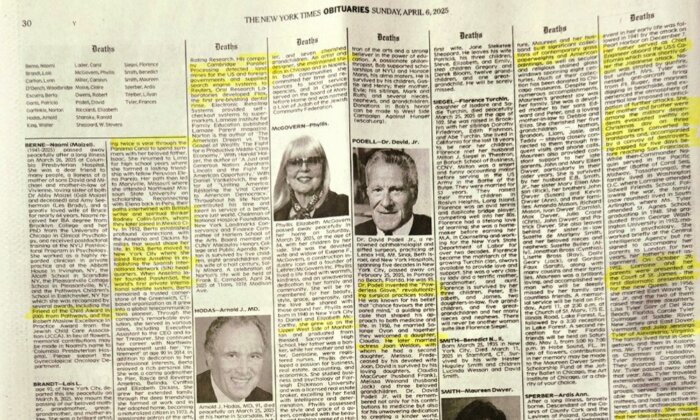

Which brings me back to obituaries. I’m not talking about the half-page write-ups of celebrities or politicians. I mean the small-print obituaries in the New York Times Sunday edition — the ones squeezed into eight columns on a single page, paid for by friends and family. These people aren’t famous. But their lives, described lovingly and vividly by those who knew them best, are often more surprising than any headline obituary. And they’re an ideal way to boost your creativity.

It’s important to read all of the obituaries on Sunday. If you filter your reading by only choosing people who are like you, then you won’t be absorbing the most different, surprising new information.

Here are two that I read one Sunday morning recently:

Berta Escurra was born in 1924 in San Pedro de Lloc, Peru. She was a follower of British writer and spiritual thinker Rodney Collin when he moved to Mexico City in 1948. In 1963, she moved to New York City and founded the Spanish International Network (SIN) with Rene Anselmo. SIN was the first TV network in the U.S. to broadcast entirely in Spanish. Anselmo later went on to found PanAmSat, the world’s first private international satellite system.

Norton Garfinkle died on March 20, 2025 at the age of 94. Garfinkle was a professor at Amherst College and a serial entrepreneur. He founded a company that detected land mines for the U.S. and foreign governments. He invented a news database search algorithm and sold it to Reuters. He developed PLAX, the first pre-brushing dental rinse. He started Electronic Retailing Systems, which provided self-checkout systems to supermarkets. He started a company that published Lamaze Parent Magazine.

See what I mean about being interesting? You’ve probably never heard of either of them. (I hadn’t.) But reading their stories introduces you to a mix of fields — broadcasting, aerospace, esotericism, oral hygiene, database design, prenatal publishing — that you’d rarely, if ever, encounter all in one place. It’s exactly the kind of conceptually distant material that helps fuel creative thinking.

Start by reading the obituaries slowly, without searching for a big idea.

Here’s how you can use the obituaries to enhance your creative cognition.

First, start by reading them slowly, without searching for a big idea. Let the details wash over you — the places lived, the professions practiced, the odd hobbies pursued. Notice what sticks.

It’s not just about learning new facts, of course — it’s about asking questions. Why was a British mystic in Mexico City? How did Spanish-language television evolve in the U.S.? What led someone to invent PLAX or build search tools for financial news decades before Google? Even if you don’t find all the answers, just posing the questions helps you flex the creative muscle that thrives on curiosity and connection.

Will any of the life stories you read cause you to have a surprising, creative insight? No one can say. But research shows that distant analogies often lead to creative breakthroughs, often in unexpected ways. What you’re doing is filling up your brain with a range of very different cognitive material.

In every person’s life story, there’s always a narrative, always a deeper principle at work. How did a woman from Peru get to Scotland, Mexico City, and then New York? How does a professor at Amherst College found so many different companies, with so many different technologies and within so many industries? Seek that deeper principle, ask “Why?”, and look for distant connections with your own life. Creativity is a daily practice available to anyone.

Keith Sawyer is one of the world’s leading creativity researchers. He has published 20 books, including “Group Genius,” “Zig Zag,” and, most recently, “Learning to See.” Sawyer is the Morgan Distinguished Professor in Educational Innovations at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.