Emily Dickinson’s Playful Letterlocking

Among the extraordinary literary output of Emily Dickinson are her “envelope poems,” short bursts of verse recorded on fragments of envelopes much like the ones we still use today. These texts, largely produced between 1870 and 1885, in the mature period of her writing, show Dickinson making creative use of a technology that was still almost brand new in her lifetime and forever associating her writing with epistolary forms. They help remind us that Dickinson was not only distinguished as a poet — she was a prolific letter writer, too, who called letters a “joy of Earth,” and she maintained lifelong relationships primarily through correspondence.

Dickinson’s letter to her brother Austin, written during her time as a student at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, Massachusetts, shortly after she turned 17 years old, is a locked letterpacket folded and sealed with that joy. Pregummed envelopes came into circulation around the time Dickinson was born (1830), so she herself would have been familiar with them alongside enduring letterlocking practices — but envelopes would still have been considered novel by her parents’ generation.

Dickinson seemed to revel in the formal opportunities presented by letters, wrappers, envelopes, folds, adhesives, and their related paraphernalia. If a letter is designed to contain a message within, what is the effect of writing on the outside? When working with containers and enclosures, what possibilities does a poet have to explore interiority, concealment, revelation, and the placement of words in relation to each other, or experiment with narrative pacing?

Dickinson’s prose letters are just as playful and interesting as her poetry when it comes to their form. In her letter to Austin (“UH6180” in our numbering system), she tells him about her recent studies of the sciences, including “Chemistry, Physiology & quarter course in Algebra,” not to mention some heavy reading in Euclid. Thinking of her family back home, she pictures them reading each other stories from the “Arabian Nights,” and stretching their “powers of imagining.” She sends a sisterly word of warning — “Cultivate your other powers in proportion as you allow Imagination to captivate you!” — before adding a humorously self-aware afterthought: “Am not I a very wise young lady?”

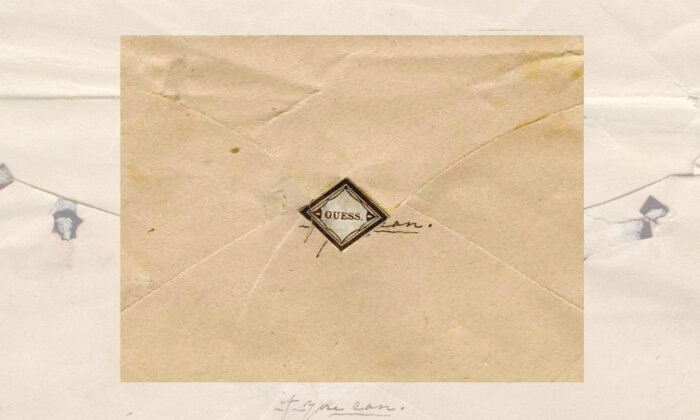

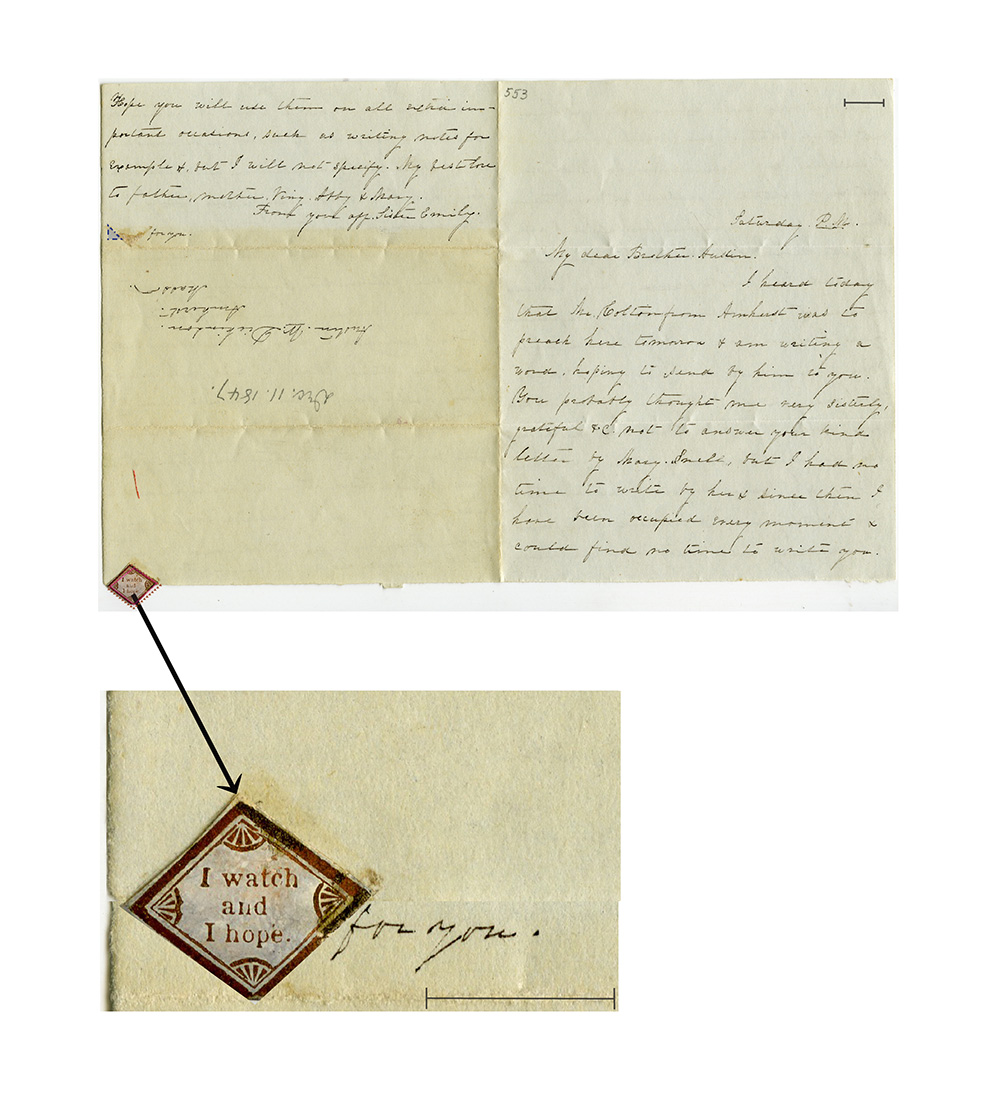

Dickinson’s attention to the practicalities and joys of letterlocking shines through at this young age: She sends her brother a box of special wafers for sealing letters, to be used “on all extra important occasions, such as writing notes for example &, but I will not specify.” The wafers are no longer enclosed in the letter, and we imagine that Austin probably put them to good use. Perhaps these special wafers were like the ones Dickinson used to adhere her own letterpacket (and the envelope into which it was then inserted), embellished with preprinted mottos (popular options at the time included “HOPE DEFERRED” or “STRIKE WHILE THE IRON IS HOT”).

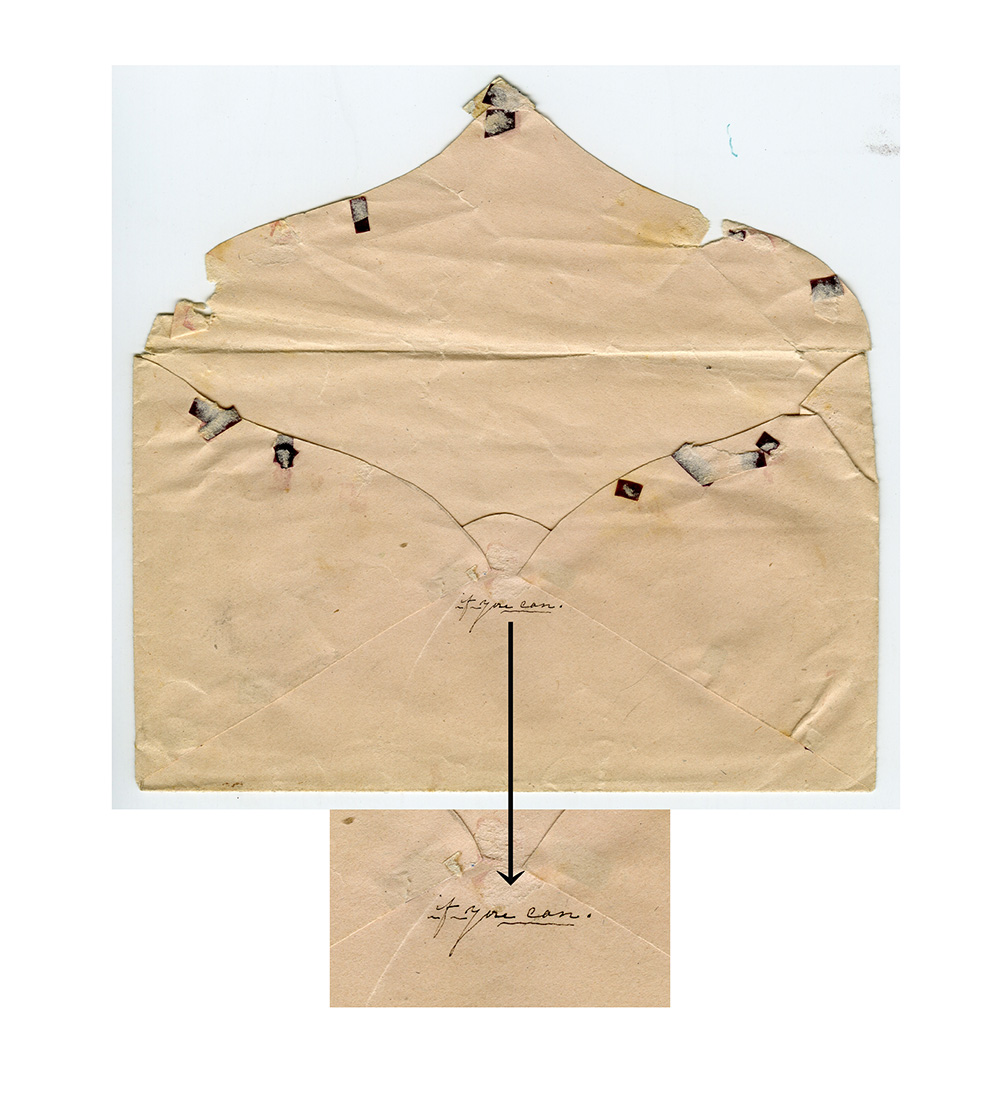

Dickinson’s message seems to end with expressions of affection to various family members — but in fact, her own use of the motto-bearing adhesive wafers continues her writing. After folding her letter, she used a wafer with the messages “I watch and I hope,” to which she added in pen “for you.” Similarly, after securing the flap on her envelope, she applied a wafer with the message “GUESS,” adding “if you can” in pen. The adhesive — and therefore the letterlocking process itself becomes part of her message. The text she added as part of the sealing process becomes the first text Austin will read as part of the opening process.

Read today without knowledge of letterlocking, the letter seems as if it ends “From your aff[ectionate] sister Emily / for you.” In fact, “for you” forms part of an opening message for her brother, produced in combination with the sticker: “I watch and I hope for you.”

One of the immediately distinctive features of UH6180 is that Dickinson combines both letterlocking and more modern technologies because she makes a locked letterpacket and then puts it inside an envelope. What are we to make of this, when this book’s starting point is an interest in substrates folded to function as their own envelopes or sending devices? Does the addition of an envelope mean that Dickinson’s sealing method no longer qualifies as letterlocking? This is an interesting gray area in our theory, but on balance we are happy to include locked letterpackets that were sent by other means; after all, lots of locked letters were included as enclosures in other locked letters over the years.

Dickinson used this more playful and elaborate letterlocking style alongside other methods, including the classic tuck-and-seal, much like the other poets, including John Donne and Phillis Wheatley. There is something pleasing to the thought of these poets — experts in the relationship between form and content — choosing from a range of letterlocking options as they finalized their letterpackets.

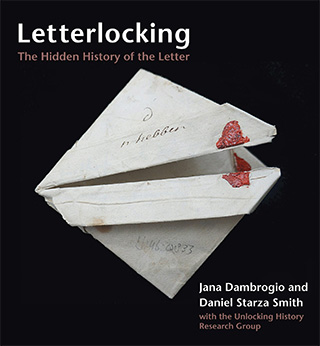

Jana Dambrogio is Thomas F. Peterson (1957) Conservator for Massachusetts Institute of Technology Libraries.

Daniel Starza Smith is Senior Lecturer in Early Modern English Literature at King’s College London.

Dambrogio and Starza Smith are the authors of “Letterlocking: The Hidden History of the Letter,” from which this article is adapted.