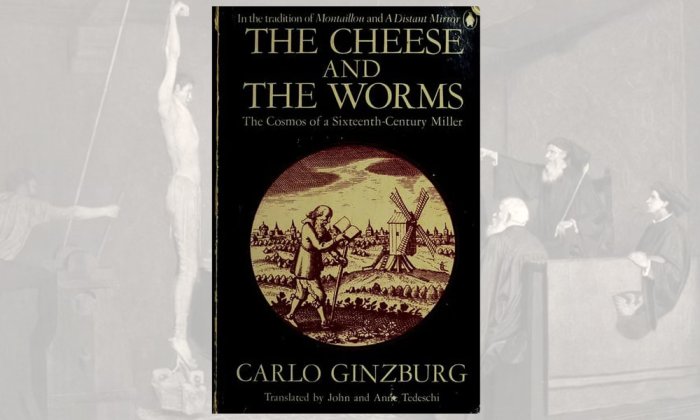

‘The Cheese and the Worms’: Carlo Ginzburg Launches Microhistory

The events took place in 1583 in a village in the hills of Friuli, under Venetian domination at the time. The protagonist is a miller in his 50s, Domenico Scandella, whom everyone called Menocchio. Summoned to appear before the court of the Inquisition and interrogated about his beliefs, he blurted out a theory on the origin of the universe: “All was chaos, that is, earth, air, water, and fire were mixed together; and out of that bulk a mass formed — just as cheese is made out of milk — and worms appeared in it, and these were the angels. The most holy majesty decreed that these should be God and the angels, and among that number of angels, there was also God. . . .”

This set Carlo Ginzburg (born 1939) wondering how Menocchio could think that God had not created the universe. The Council of Trent had come to a close 20 years earlier, and the evangelization conducted by the Catholic Church had reached all the parishes in the Italian Peninsula. Nobody, be they illiterate or cultivated, could doubt the account in Genesis. Was Menocchio simpleminded? No. He was stubborn, talkative, and eccentric, but he was not mad. Had he been in contact with one of those clandestine Anabaptist groups still active in the region? No. The interrogation showed that Menocchio did not contest infant baptism. Had he learned this curious theory mixing cheese and transcendence in a text circulating despite the censorship? This was not the case either.

Menocchio was an autodidact who had stumbled his way through barely a dozen books that he had borrowed or bought himself. Most of these books gave a highly orthodox treatment of religious subjects; a few had been placed on the index (such as the Decameron). But in none of them could Ginzburg detect a cosmogeny comparable to that of the miller. At this stage of the inquiry, he was as disconcerted as the judges had been four centuries earlier, confronted with a heresy they were unable to identify.

But Ginzburg formulated a new hypothesis: Not only had echoes of reformed theses disputing the ecclesiastical hierarchy reached Menocchio, who had read some nonorthodox books, but he had interpreted them in the light of an oral tradition “deeply rooted in the European countryside, that explains the tenacious persistence of a peasant religion intolerant of dogma and ritual, and tied to the cycles of nature, and fundamentally pre-Christian.” Precisely because it was oral, such a tradition tended “not to leave any trace, or to leave only distorted traces of itself.” And it was only by comparing these tenuous traces that one could work back up to the “popular roots of much of high European culture, both mediaeval and post-mediaeval.”

Ginzburg had been driven toward this hypothesis by earlier research he had conducted into fertility cults in Friuli, which he had likewise approached through the trials of the Inquisition in “The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries” (1966). A few years later, his exploration of how witchcraft related to oral culture had led him to write a book on rituals of death across Eurasia: “Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath” (1989). But it was “The Cheese and the Worms” that became an instant classic.

In 1976, Ginzburg was infringing not one but several taboos in historical scholarship.

For, in 1976, Ginzburg was infringing not one but several taboos in historical scholarship. Like many other historians of these years, he drew on anthropology and preferred the history of ordinary people to that of elites. But from the outset he stood out for rejecting two approaches that were then in the avant-garde of research: quantitative methods (used to apprehend demographic behavior but also cultural and mass phenomena) and the influence of Foucault, which encouraged historians to analyze state power on the basis of administrative regulations and discursive forms, rather than the experience of actors. Through Menocchio, Ginzburg was expressing both his confidence in the possibility of reaching oral culture through written sources and the ethical tension pushing him toward reconstructing this experience.

Above all, Menocchio became synonymous with “microhistory.” His life course, though not unique, was anomalous, and this border case, because it was truly extraordinary, was of irreplaceable heuristic value: It provided a way of unearthing evidence otherwise lost from view. Shortly after, in “Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method” (1986), Ginzburg named his method the “index paradigm” (in reference to the historian of science Thomas Kuhn), presenting it as an alternative to the paradigms that were then dominant in history and social sciences.

“The Cheese and the Worms” was translated into 26 languages and has attracted much praise and criticism. The changing responses it has engendered are testimony to its longevity. In the 1980s, when the linguistic turn was triumphant, Dominick LaCapra proposed a rhetorical and hermeneutical reading of Ginzburg’s book in “History and Criticism” (1985), noting the equivalent of a psychoanalytic “transfer” between Ginzburg and his protagonist. Both of them, according to LaCapra, used writings to find confirmation of their prior convictions. Nowadays, when the relation between Europe and Islam is a central preoccupation, it is a different trace, which Ginzburg touched on only lightly, that has given rise to new inquiries (such as Pier Mattia Tommasino’s “The Venetian Qur’an: A Renaissance Companion to Islam,” 2013): the possibility that Menocchio found the answers to some of his worries in the first translation of the Qur’an into the vernacular, which was in fact a vulgarized and polemical synopsis of Christian knowledge about Islam, and a collection of stories about biblical prophets and figures who would have been readily identifiable to a 16th-century reader. What new provocations will “The Cheese and the Worms” inspire in the future?

Francesca Trivellato is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Early Modern European History at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ. This article is excerpted from the volume “A History of the Social Sciences in 101 Books.”