Injuries of Assimilation: The Hidden Toll of Military Labor on Noncitizen Soldiers

There are two mostly disconnected stories when it comes to military labor and life after leaving the military. According to one story, a patriotic youth gains valuable skills while keeping America safe, and serves as a model citizen afterward, enjoying the honor of being a veteran, as well as educational, health care, and housing benefits. The other story evokes different images altogether. A disheveled veteran sitting on a sidewalk behind a cardboard sign or panhandling on a highway ramp. Debilitating physical and mental injuries. Women soldiers raped and murdered. This second story focuses on the damage that military workers sustain in the service of the U.S. empire, and the current of stigma that runs under the honor heaped on veterans.

The narrative of damage and stigma is almost never told about immigrant veterans. The story of skills, honor, and social mobility dominates the scholarship and advocacy fields, framing military labor as a way for immigrants not only to gain skills and social mobility but to acculturate and integrate into U.S. society. It draws on the deeply entrenched narratives of immigrant assimilation, a process whereby immigrants and their children are supposed to become less and less different from the mainstream.

The reality of immigrant labor in the military and the transition to civilian life contain elements of both stories: mobility and despair, belonging and exclusion. Some immigrants move through their time in the military relatively unscathed, then build civilian lives that work for them and check off boxes for conventional success, including going to college and owning a home. Others, as we will see, struggle mightily.

Immigrants who work in the U.S. military work in a context where injury and harm are expected, normalized, and even valorized. They experience the same pressure to push through physical and mental pain as non-immigrant military workers. However, some immigrants whose access to U.S. citizenship hinges on their job in the military experience extra pressure to downplay their injuries and not seek help, lest they be deemed unqualified. At the same time, immigrants face suspicion that they are faking injuries in order to get a medical discharge from the military once they get citizenship and are pressured by their coworkers and commanding officers to prove otherwise. The military consumes immigrant bodies, facilitated through the linkage of citizenship to stoicism and denial of health concerns.

Immigrants who work in the U.S. military work in a context where injury and harm are expected, normalized, and even valorized.

Many of the immigrants I interviewed for my book “Green Card Soldier” mentioned serious injuries and harmful consequences to their physical and mental health stemming from their military work. Out of 50 participants who progressed past basic training in the military, 22 spoke about the damage they sustained. This is remarkably high, considering I did not directly ask about health issues, some had not been in the military for very long at the time of interview, and many were in the reserves, where part-time work reduces the risk of injury. Those who talked about their injuries brought up serious issues without which it would be difficult to understand their military careers and life stories.

Some physical injuries occurred in basic training, mere weeks into enlistment. Mary, from Kenya, fractured her hip in basic training. Ranil broke his tibia in basic training. Both stayed on, recovered, and completed their contracts. Other injuries occurred after boot camp, during training, or during deployment. Truda described a serious knee injury sustained during army training, which required multiple surgeries, resulted in a medical discharge from the military, and caused her to spiral into years of depression and addiction. Gilberto injured his shoulder while training in the Marines. He was medically discharged after four surgeries to repair it proved unsuccessful. John’s career plans in the army were cut short by a knee injured while training, which left him unable to walk for the better part of a year. He left the military and struggled with depression. Jack had three knee surgeries to try to repair an injury he sustained while working in the military and had to leave at the end of his contract. Heena fractured her hip, both ankles, and a wrist while parachute jumping.

Military workers also regularly risk exposure to harmful chemicals, drugs, and other substances, at home and abroad. The Department of Veterans Affairs lists multiple categories for exposure to hazardous chemicals and materials that could qualify veterans for disability compensation, including being used as subjects for medical research; exposure to unspecified toxic chemicals during the Gulf War, in Afghanistan, and in Iraq; being around “warfare testing” of chemicals for various projects; exposure to radiation; and more. Vaclav experienced mental health problems when he returned from a deployment in Afghanistan:

I was stressed out, I was taking anti-depressants, I couldn’t sleep at night. You know, it just really ruined my health, left and right, all the chemicals that they had us use over there, you know, throughout the army. And another thing was, in the army, when something had to be done, you had to use like hydraulic fluids or epoxy or what-have-yous and there’s no protective gear, you know, well they wouldn’t be like, “Well, okay, we’ll just wait for the shipment of protective gear to come in and you know, do it next week.” No! Hell no, you go out there and you do it now!

Vaclav left the military and found a job, but he was struggling. The VA classified him as 50 percent disabled. He continued to take medications and receive psychological counseling. Vaclav was not alone. Veterans, in general, report declines in emotional and mental health. And even adjusting for age and sex distribution, the veteran suicide rate has been 50 percent higher than in the general population between 2013 and 2018.

Jim described his exposure to drugs during the first Gulf War in Iraq and the effect it had on his health:

Training in the desert, we suffered a lot. We were induced [sic] drugs. We were physically trained, mentally trained, and we were drug induced to be able to kill. Because my unit is what is called a do or die unit, whereby what we do is we go in, we don’t take prisoners, we just take out airports, take out cities, we just go through, that’s what we do. Even before the war, a lot of soldiers in my unit had to go back because the training was extreme. They weren’t able to handle it. And therefore, a lot of them were kicked out of the military. I had even one officer who actually was kicked out because of depression. He ended up shooting his gun at someone. Yeah. And there was a lot of fights because the drugs we were given which made us want to fight.

Jim damaged his back in Iraq while operating ammunition. Feeling a sense of obligation to his unit, he pushed through the pain and kept working. He started to drink and smoke cigarettes and became addicted to crack cocaine. For many years after leaving the military, Jim struggled with addiction and depression. He attempted suicide multiple times and was hospitalized. Jim said that when he first left the military, he went to a VA hospital but was ignored when he shared his PTSD symptoms: “They gave me medications for physical issues, but not for mental issues.” A 2011 study found that 20 percent of veterans with mental health disorders in New York State did not access mental health services. Research shows pervasive delays in needs assessments for veterans, with concomitant lengthy delays in military benefits and pensions. More than 20 years passed before Jim went to the VA again. This time, he was classified as 100 percent disabled, but was not given any retroactive compensation for all the years that passed between the harms he sustained in the military and his second VA visit.

Research by anthropologist Ken MacLeish demonstrates the way military workers’ bodies and lives are used up to fulfill the needs of their employer, ignoring their injuries and destructive behavior when their labor is needed, and spitting them out when downsizing. When I spoke to him, Jim, in his early 50s, lived in unremitting pain. He took over 20 medications and went to the VA hospital four days a week for appointments addressing his many medical problems. As MacLeish writes, “War can become too much in the people who make it.”

Mental health issues afflicted many immigrants whom I interviewed. Researchers note that many veterans report feeling stigma and are discouraged from asking for help for their mental health symptoms. Military culture not only stigmatizes workers with mental health illnesses as weak, but also puts up barriers to their promotion within the military. In the stigmatization of mental fallout from military labor, we glimpse barriers put up against examining the substance of what the U.S. military is doing and how it does it. That is, workers’ mental health is a symptom and judgment of empire in itself, one that proponents of the military as an integrative institution must downplay. When framing the military as an avenue for inclusion of marginalized populations, it becomes necessary to bracket the widespread damage of military labor on those who perform it, even when they are not deployed to a conflict zone.

Nothing short of a missing limb or two seems to be real enough as a disability.

There is an additional stigma to experiencing mental health problems for those who have not been deployed. Brian described difficulty being in crowds, trouble concentrating, and obsessive checking for threats. Although these symptoms pointed to possible PTSD, he did not feel comfortable seeking help: “I don’t want even to think that I have it because I don’t want to have a crutch to lean on. I want to just be able to be normal,” he told me. “You know, there’s so many other people that have lost limbs, there’s those who’ve had concussions, or have lost a best friend, or whatever it might be that have more than enough reason to have post-traumatic stress. I don’t believe that I have ever experienced anything to warrant it.” Brian did not experience deployment, and hence did not feel justified in claiming injury from his military work. In fact, military workers and veterans whom I interviewed moved in a culture of militarism that both valorized wounded soldiers and scrutinized and stigmatized them, all while routinizing harm and injury in military labor.

The valorization of the wounded soldier is readily apparent in the public sphere through honors bestowed on selected disabled veterans during public events, usually on those with physical disabilities. A memorial dedicated to disabled veterans was erected in Washington, DC, in 2014. This valorization does not consistently embrace veterans suffering from traumatic brain injuries, PTSD, and other mental health issues stemming from their military labor, not least because veterans experience high levels of criminalization and incarceration tied to their mental illness.

Anthropologist Zoë Wool characterizes media coverage of soldiers’ struggles with mental health as evoking “the pathologizing monster-out-of-place soldier figure.” Former President Trump’s minimization of traumatic brain injury as headaches after an explosion in Iraq in 2019 injured U.S. military workers demonstrates both the skepticism around less visible injuries and the fact that military valor is firmly associated with toughness. Nothing short of a missing limb or two seems to be real enough as a disability. There is also the suspicion that veterans might be faking it to receive disability benefits.

Like other military workers, immigrants experience the normalization of harm and injury, and the pressure to push through the pain. Miguel described a commanding officer forcing him to hold onto a part of a machine that gave him an electric shock: “Hold onto this thing and crank it up, electricity go through it and I flew to the wall [gestures being knocked down]. Which didn’t bother me that much because all you are doing is painful training.”

Fajing described the extent to which injury was normalized: “All the soldiers in the service have some kind of broken bodies, to an extent. Even my mentor, he’s a pretty good shaped man, he got back problems. And he got anxiety problems. I have a lot of health issues as well. I have lower back pain. I have a chronic sprained ankle. And then, I have some anxiety issues going on as well. But I don’t try to get out of the army, try to get away [from] what I’m obligated to do with those excuses and issues.” Fajing had been working in the military for five years at the time that I spoke to him. Despite his injuries, he strove to differentiate himself as a good soldier against those who supposedly claim injuries to get out of their military contracts. As a MAVNI recruit and an Asian soldier racialized as a forever foreigner, it is likely that Fajing had to go extra lengths to prove his worthiness as a soldier.

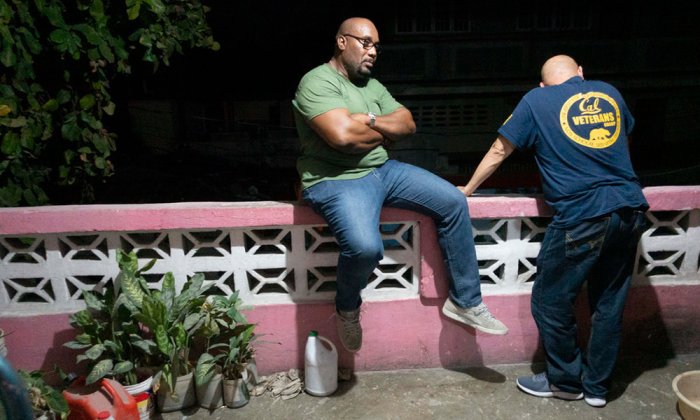

Fajing was not alone in describing the normalization of injury. In 2019, when I traveled to Ciudad Juarez to meet with deported veterans living there, I was struck by the way they spoke about their injuries. Over breakfast in a large restaurant, the four men recounted injuries they sustained as soldiers. The common threads that emerged from these accounts were how routine these injuries were and the expectation that no medical care would be provided by one’s superiors. Laughing at the memories of their wild youth, the veterans recounted falling from great heights during training and being unconscious for many minutes, and trekking miles with broken ankles or ribs. They told me it was not cool to report injuries during training, and during deployment, it was not really a situation where you could report it. Anyway, they said, their superiors would just tell them to take a painkiller. Although several were only in their early 40s, their grave bodily injuries made them seem much older. They jokingly brushed off the callousness with which their injuries had been ignored and dismissed, yet it was clear how their then-young bodies had been used up by the military, which extracted their labor and treated them as disposable even before they were deported. The lack of medical attention at the time of the injury meant no record of it — and, thus, difficulty in proving disability that resulted from work in the military.

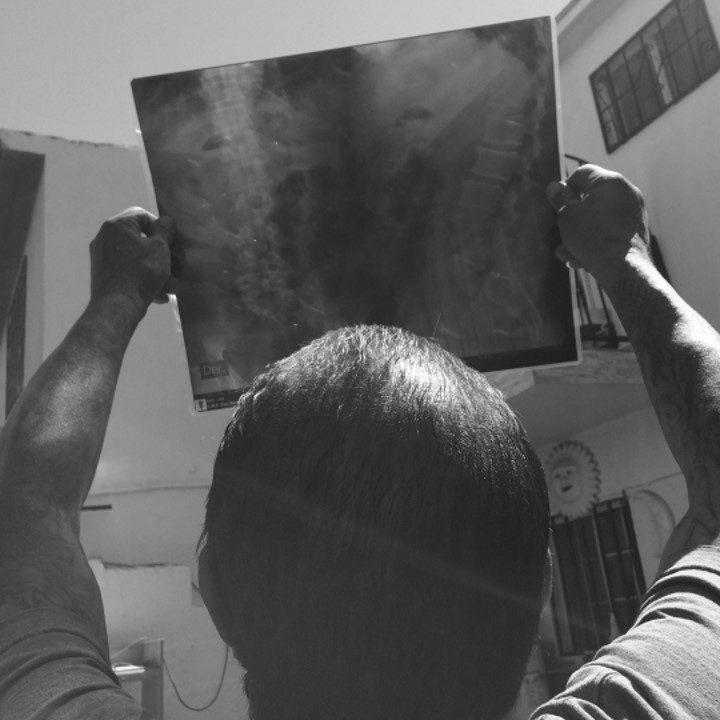

When I interviewed one of these veterans, Hector, one on one, he told me that he sustained multiple head injuries while jumping from planes in the army, which meant difficulties concentrating and memory lapses: “I don’t know when it happened, but, basically like every fall that you have, the way you land, your body impacts the ground really hard. I remember on one occasion I was unconscious. I don’t even know for how long. But like, you know, you’re young, you’re 18 years old and you don’t want to be a wuss, you don’t want to go on sick call, and have a profile. When you get a profile you can’t do anything, so you suck it up. You suck it up, dust it off.”

These repeated head injuries were not noted in his army medical record, although his broken back and ankle were. Hector had been eager to jump from planes to escape the stigma of being a “leg,” or someone in an airborne unit who has not yet jumped. The stories of injury told by these immigrant veterans and military workers bring home the reality that although they tend to view the military as a vehicle of social mobility, in some ways, their experience is the same as that of their parents who are farmworkers and factory workers. Just as the bodies of Hector’s parents were prematurely aged through the repeated and untreated strain of working in factories, mowing grass, and picking up cans, so is Hector’s body worn down by military work, self-medication, and chronic disease.

Just as the bodies of Hector’s parents were prematurely aged through the repeated strain of working in factories and picking up cans, so is Hector’s body worn down by military work, self-medication, and chronic disease.

These are the literal injuries of assimilation, reinforced by the culture of warrior masculinity that requires military workers to push themselves through life-changing injuries and not show pain. As Hector put it, “you don’t want to be a wuss” or be known as drawing attention to your injuries. In fact, some scholars argue that the epidemic of military suicides is connected to military masculinities that force military workers and veterans to internalize their distress.

Fan was yet another person to be injured during basic training, and felt she had to demonstrate her recovery to her commanding officers. Fan missed some training sessions because of her injury but still graduated from basic training on time. She pushed through the pain to pass all the tests she needed to pass. By performing a fast recovery from injury, she demonstrated her fitness for the military. Fan and many other immigrants I spoke with felt extra pressure to demonstrate their excellence in military work because they faced scrutiny as foreigners, people of color, women, sexual minorities, or a combination of these.

Manuel told me that he did not pursue naturalization because his time between deployments was consumed by trying to recover from the injuries he sustained while deployed: “After the first deployment . . . I was too busy with physical therapy, and I was actually trying to stay in the Marine Corps. Because of my injuries the talk initially was that they were going to medically separate me, but I was very focused on doing PT [physical therapy] and getting back into really, really good shape and improving my health in that state.” Manuel, like Fan, was working on his injured body to be able to hang onto the pay and benefits of a job that caused his injuries in the first place.

When Heena broke her hip jumping from an airplane and had to take a break from intense physical training while it healed, she remembered being pushed to recover faster and told that the military could not keep her while injured. As someone who enlisted through the MAVNI program, she faced suspicion as well. In fact, despite the MRI that clearly showed her fractured hip, Heena’s commanding officer accused her of faking it:

The first sergeant came and he was like, “You MAVNIs are just trying to get med boarded.” And he pointed at me and he was like, “You were supposed to go to civil affairs qualifications course and you’re just here faking an injury.” That’s how he put it. And that was when I was just so frustrated that I went to his office and I was like, “You know I’m not faking an injury. And I want to get out of this unit and I’m going to qualifications course next week, just send me.” And he did. He was like, “Okay. You have to jump before you go.” And I hadn’t jumped in a year and a half after the injury. And I was like, “Okay, I’ll jump.” And I just jumped [the] next week, and a week after that, I was in training. So it wasn’t an obstacle. It was just to prove them wrong [laughs] and then, the frustration of how some MAVNIs are being treated. I think I was treated bad too but every time they said something, I took it in a way like, “Hey. I need to prove this person wrong and do something better.”

To be sure, Heena was still in pain when she decided to start jumping again, and she went on to sustain multiple additional injuries. She wanted to prove that she was fit for military work but she had her doubts as well: “I really wanted to do this and I was also thinking, ‘I broke my hip. Why am I doing this? I’m going to have to go jump again.’” After many more jumps and multiple additional bone fractures, Heena finally decided to stop jumping.

If reading these more egregious examples raises the question of why people would put themselves through such harm, we must keep in mind that workplace injury, exploitation, abuse, bullying, and discrimination organized through racial, gender, disability, and other hierarchies structure the civilian world as well. These are constrained choices in a deeply unequal society. In fact, soldiers who volunteer for repeated and grueling combat tours that place them at heightened risk in order to collect untaxed combat pay have much in common with migrants who work long days and live a dozen to an apartment in order to save enough to build a house, pay off debt, or start a business back home. Both are wringing the utmost out of their bodies — with long-term damage — and postponing the business of living. Both are held up as examples of work ethic and sacrifice.

What is labeled as service in the U.S. military is physically and mentally harmful work, but military labor is not just another job. The work of U.S. military includes protecting imperial resource extraction, enforcing political regimes benefiting U.S. capital, and expanding and conquering new territory for further exploitation. Inside the United States, the military and militarized law and immigration enforcement agencies crush popular resistance to resource extraction and white supremacy and maintain the violence of the border with Mexico. The price of assimilation into U.S. society, then, is participation in this theft and destruction. When we tout the military as an integrative institution, we must be honest about the violent nature of this integration on the immigrants but also the oppressive continuities with the civilian world in the United States and the globe at large.

Sofya Aptekar is Associate Professor of Urban Studies at the City University of New York School of Labor and Urban Studies. She is the author of “The Road to Citizenship: What Naturalization Means for Immigrants and the United States” (Rutgers University Press) and “Green Card Soldier: Between Model Immigrant and Security Threat,” from which this article is adapted.