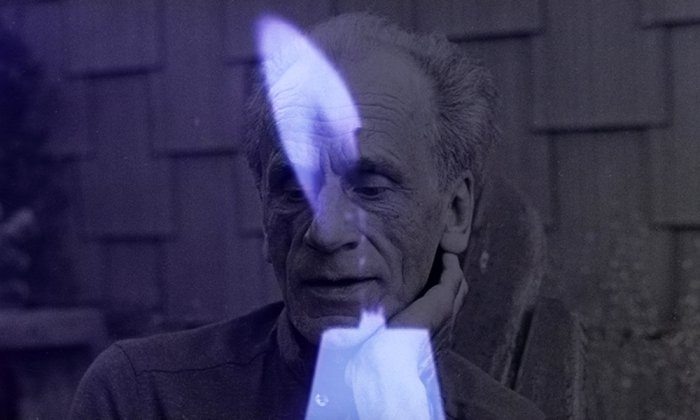

Theater of the Spirits: Joseph Cornell and Silence

Joseph Cornell’s box sculptures represent muted worlds, where the only people are images collaged onto the back wall, disappearing into the paint. Movement is hinted at by the suspension of movement: Two wooden balls nearly touch. Wooden birds sit frozen, glancing sideways through a glass wall.

Poets are drawn to the quality of silence in Cornell’s work. John Ashbery, Octavio Paz, and Charles Simic have all written of it. Ashbery felt Cornell’s work recovered from childhood “the dazzling, single knowledge we get from the first things we see in life, things we look at daily and come to know through long, silent experience.” He describes a sort of contemplative wisdom born of reflection, rather than the worldliness of a man of action who has traded innocence for experience.

Objects never really become objects, but retain hidden mythic qualities, which Cornell the magician (as Ashbery calls him) restores to the patient viewer. In this brief passage on silent experience, Ashbery pays homage to Cornell’s subtlety. Unlike the provocative grand gesture more common in late-20th-century art, Cornell’s work rewards, and almost commands, the stillness of solitary reflection.

In his poem “Objects and Apparitions,” dedicated to Cornell, Octavio Paz writes, “You constructed / boxes where things hurry away from their names.” Paz finds Cornell’s images excessive to language. They shed whatever words try to attach themselves and exist on a plane speech cannot touch. Indeed, Cornell’s work has often been called literary, but Paz also writes of the transformative power of Cornell’s art, changing ideas into sculptures, leaving words behind. Their visual poetry touches Paz the poet, for whom meaning is primarily constructed through language.

It is as if Cornell uses silence as a key to the universe.

Cornell’s later sculptures were almost bare. Sometimes a few small pieces of white wood were the only objects. Again, quiet connotes solitude: an interior space hinted at by the “few figures,” their stillness, and the silence endlessly surrounding them. In Charles Simic’s book of poetic meditations on Cornell’s art, he describes Cornell’s expanse of silence as “vast, cosmic.” It is as if Cornell uses silence as a key to the universe, taking us beyond one location with its specific, identifying sounds, to an unlimited space of devotion — what Simic calls the “cosmic church.”

Cornell created a fragile, oneiric cinema, too, which in its silence offers the impression of solitude Simic feels in Cornell’s work. Cornell spliced and reconfigured old films to create poetic narratives, hinting at internal life, receding from action in the world.

Cornell’s first collage film, often called his masterpiece, was “Rose Hobart”(1936). Most of the footage comes from the 1931 jungle melodrama “East of Borneo.” In the original film, a young American woman, played by the actress Rose Hobart, travels to the jungles of Borneo to find her husband, who is now the personal doctor to a Sorbonne-educated jungle prince. The prince tries to seduce Rose, and she tries to rescue her husband.

Cornell has removed the plot of the film almost entirely. He edited the hour-and-twenty-minute film down to 20 minutes. With all the action gone, what remains are interstitial moments: a loaded glance, a glass being lifted, palm trees swaying in the wind. He removed the sound, slowed the film down to silent speed, and played a record of Brazilian music while projecting it.

Filmmaker and journalist Brian Frye describes the combined effect of erased sound, deceleration of image, and the addition of exotic music: “As a result, the characters move with a peculiar, lugubrious lassitude, as if mired deep in a dream.” In his classic book on American avant-garde film, P. Adams Sitney observes that “By stripping it of its dialogue and mood music, he transformed its banality into an oneiric mystery. By projecting ‘Rose Hobart’ at silent speed, Cornell retarded the gestures and action of ‘East of Borneo,’ not enough to make them look like slow motion, but to lend them a nuance of elegance and protraction.” Cornell plays the film at silent speed while restoring to it the poetic qualities of silent film.

He turned a jungle action picture into an underwater ballet, a fragmented tropical dream. Smoldering passions that once drove the film are now only hinted at by a glimpse of a volcano behind a curtain, a crocodile descending into water, a line of dancing girls in sarongs.

When Salvador Dalí saw “Rose Hobart,” he knocked over the projector in rage and allegedly yelled, “Joseph Cornell, you are a plagiarist of my unconscious mind!”

The filmmaker Jonas Mekas believes Cornell’s films are “so unimposing that it’s no wonder his movies have escaped, have slipped by unnoticed through the grosser sensibilities of the viewer, the sensibilities of men who need strong and loud bombardment of their senses to perceive anything.” But when Cornell first screened the film, it hardly slipped past the notice of one prominent audience member. Salvador Dalí knocked over the projector in rage, ending the screening. Legend has it he yelled, “Joseph Cornell, you are a plagiarist of my unconscious mind!” Dalí, at the forefront of the avant-garde, had conceptualized such a film, but had not yet mentioned it to anyone. Cornell, a reclusive young man from Queens, had made work that threatened an artist he called “a master.” Aside from Dalí and his wife, no one in the room that night understood what had happened.

Cornell once wrote a paean to the sublime nature of silent film, in the form of an appreciation of the actress Hedy Lamarr, who he felt retained some of the elusive qualities of that extinct medium. Published in View magazine, it was titled “Enchanted Wanderer.” This essay gives us a clue to what Cornell did that so startled Dalí, but remained incomprehensible to others. Cornell begins “Enchanted Wanderer” with this passage:

Among the barren wastes of the talking films there occasionally occur passages to remind one again of the profound and suggestive power of the silent film to evoke an ideal world of beauty, to release unsuspected floods of music from the gaze of a human countenance in its prison of silver light.

Silence allows for poetry. The intrusion of sound destroys the possibility of subtlety and suggestion, the formal communication of an ideal. Speech creates a “barren waste.” The “mute gaze” is profound and overwhelming because unlike speech, silence can ascend to the sublime.

Cornell continues:

But aside from evanescent fragments unexpectedly encountered, how often is there created a superb and magnificent imagery such as brought to life the portraits of Falconetti in “Joan of Arc,” Lillian Gish in “Broken Blossoms,” Sibirskaya in “Menilmontant,” and Carola Nehrer in “Dreigroschenoper?”

It is significant that he calls these “portraits.” Cornell’s assistant and collaborator, Stan Brakhage, describes the film “Rose Hobart” as an expression of Cornell’s adoration for the actress Rose Hobart. He calls the film a communication of her essence as a human being: in other words, a portrait.

Rose’s image is constantly on the screen. Cornell’s film is so exclusively about Rose that we rarely see any other person with whom she is speaking. The camera barely lifts its gaze from her. Brakhage writes:

[Cornell] took this movie, and . . . cut it down to what he cared about the most. He began making it a film really about the deepest of all possible problems that women can have and how desperate their situation is, and the magics that they have and how fragile those are, and made a piece that’s, I think, one of the greatest poems of being a woman that’s ever been made in film, or maybe anywhere. This is like carving out slowly the deep essence of this movie that he could see because of his love of Rose Hobart.

In Brakhage’s understanding, Cornell took “East of Borneo” and pared away everything that was not an expression of the essence of Rose Hobart. Michelangelo is thought to have said, “To determine the essential parts of a sculpture, roll it down a hill. The inessential parts will break off.” This is what Joseph Cornell did with “East of Borneo.” What remained was Rose Hobart.

As Cornell’s “Enchanted Wanderer” continues, he writes,

And so we are grateful to Hedy Lamarr, the enchanted wanderer, who again speaks the poetic and evocative language of the silent film, if only in whispers at times, beside the empty roar of the sound track.

By removing the invasive soundtrack of “East of Borneo,” Cornell lets Rose speak through “mute gaze” alone. He erases the “empty roar” that might interfere with understanding her fragile, soundless communication. No longer speaking in dense, clumsy language, Rose is rescued from the mundane jungle drama and restored to the realms of poetry. Sitney interprets “Enchanted Wanderer” as it relates to “Rose Hobart”:

[T]wo principles of cinema emerge: that facial expression and gesture are its essential language and, more crucially, that the coming of sound has destroyed the immanent spiritual music of films. In this difficult time for cinema — the era of the sound film — the “poetic and evocative language” can appear only in “evanescent fragments” and their “realms of wonder” are necessarily mediated by the memory of silent films.

Cornell understands that Rose is a spiritual heiress to the world of silent film. She is somehow misplaced in a sound film, and, as he did for tragic historical figures such as Lorenzo de Medici and Paolo and Francesca in his sculptures, in this film he rescues her. Silence will reveal her spirit.

Paz has called Cornell’s sculpture a “theater of the spirits.” “Rose Hobart” is almost literally that. Cornell has created a ballet in which the only dancer is the spirit of Rose Hobart as he perceived it.

No longer speaking in dense, clumsy language, Rose is rescued from the mundane jungle drama and restored to the realms of poetry.

Toward the end of “Enchanted Wanderer,” Cornell writes, “Like those portraits of Renaissance youths she has slipped effortlessly into the role of a painter herself.” This is the secret of Cornell’s collage film. He is not painting a portrait of Rose; he is collaborating with her to create her self-portrait. He helps her do this by editing out what is not Rose, by removing the sounds of the outside world, even by removing her own voice — her communication with other people, external reality. All we have left is interior experience, a patiently sketched watercolor of inner life.

The film opens not with a shot of Rose Hobart, nor even with footage from “East of Borneo,” but with a shot of people looking through binoculars at something beyond the frame. This is a reference to Eugene Atget’s photograph, “The Eclipse,” once the cover of the journal Surrealist Revolution.

In Atget’s photograph a crowd stands on a bridge looking at an eclipse occurring outside the frame. They have no idea that they are the subjects of a photograph. From their collective action, we gather they think the subject is elsewhere: in the sky. But the subject becomes the crowd, the direction of their gaze, the way they watch the eclipse. They unwittingly give us a glimpse of themselves in natural positions, not posing for the camera, but engaging with their environment.

Walter Benjamin identified Atget as a proto-Surrealist because his photographs implied “a salutary estrangement between man and his surroundings.” In this photograph, the object of the crowd’s gaze is extraordinarily distant, completely unreachable. They are focused intently on something they can never touch. Atget and the crowd are analogous to Joseph Cornell and Rose Hobart. Cornell selects those moments of the film when Rose reveals herself, when hidden emotion and vulnerability emerge, as if she were caught unaware like the crowd on the bridge. And Cornell’s subject, however devoted to her he may be, will always remain beyond his grasp. He is not interested ultimately in the image of Rose Hobart, or even the living woman, but her spirit, the mystery of her existence.

Writing about “Enchanted Wanderer,” Sitney calls Hedy Lamarr “a metaphor for the mediation of the broken and fragmented sound cinema. Identification with her dramatizes the cinephile’s eagerness and distance from what is attracting him or her.” In the case of Rose Hobart, Cornell is attracted to what is ultimately distant from him: the interior life of another human being.

In order to approach this, his first step was to remove the sounds of the world. By silencing the actors, the sound effects, and the ambient noise of the locations in the film, Cornell gave it a glaze of interiority. We are further removed from the actual world of the film, and retreat into contemplation of it. The heroine, whose words were futile, and the prince, whose words were deadly, are both changed to mute figures moving around the screen. Their verbal battles become ballets of yearning without any clear objective. We see Rose in almost every shot, and so identify with her perspective. We have moved from the world of the film to the world of Rose Hobart.

As Frye writes, “the world appears as a sort of strange theatre, staged for her alone.” Cornell works his magic. Her expressions of emotion are collaged together until we are overwhelmed with images of Rose Hobart feeling. This becomes, as Brakhage said, the subject of the film.

The images are overlaid with exotic music building slowly in complexity and tension, then relaxing back to its original strains. When Cornell screened the film, he would alternate between both sides of the same record, creating a sound collage to match the film collage on screen. The intermittent rupture is momentarily jarring, but the music soon flows back into the environment of the film, as palm trees cast dark shadows and native men carry torches along the river. The exotic is this Hollywood version of a jungle, but it is also Rose Hobart herself, the unreachable continent. Like the music, Rose is beautiful and haunting, intriguing but unstable. If we feel we are approaching her, the scene shifts abruptly, the music flips to the other side of the record.

If we feel we are approaching her, the scene shifts abruptly, the music flips to the other side of the record.

Just as silence allowed access to interiority, so music was a route to inner life. Cornell’s assistant Larry Jordan says, “Music was important to Cornell. He talked as much about that as anything else. He talked about a man he’d known who was a violinist who played Debussy in a certain way . . . it was something special, the way that this man was inside the real Debussy.”

The record “Brazilian Holiday” does not itself transport us to the inner depths of Rose Hobart’s being. It does not lead us “inside the real” Rose Hobart. But it paves the way, bringing a dreamlike ambiance to the film, preparing us for something foreign and captivating. Sitney calls Cornell’s films “the area where the conscious and the unconscious meet.” As Cornell played the record — slowing it down and flipping it back and forth unexpectedly — it was the soundtrack for the meeting of conscious and unconscious, for the uncertain terrain leading from a person’s existence in the exterior world to the dark, mysterious interior.

Jonas Mekas writes that Cornell’s films have “something to do with retracing our feelings, our thoughts, our dreams, our states of being on some other, very fine dimension from where they can reflect back to us in the language of the music of the spheres.” In “Rose Hobart,” Cornell collages together a portrait of the unknowable woman, whose interior life remains forever elusive.

In his essay “On Dolls,” Rilke imagined a child dying, clutching a doll. In his scene, a tiny soul arises in the doll to mirror, or witness, the disappearing soul of the child. So, in “Rose Hobart,” Joseph Cornell mutes the exterior world to more clearly witness the ephemeral spirit of another person. The faltering appearance of her spirit forms a silent mirror, faintly, tentatively, reflecting his own.

Catherine Corman is the editor of “Joseph Cornell’s Dreams” (2007, Exact Change). Her book of photographs, “Daylight Noir: Raymond Chandler’s Imagined City,” was included in the 2009 Venice Biennale. Her writing has also appeared in the Times Literary Supplement and Vogue Italia, and on the websites of The Paris Review, The Economist and McSweeney’s.

This article is excerpted from the volume “Sound Unbound.”

References

- Ashton, Dore (1974). “A Joseph Cornell Album.” New York: Viking.

- Benjamin, Walter (1979). “One-Way Street and Other Writings.” London: Verso.

- Caws, Mary Ann (1993). “Joseph Cornell’s Theater of the Mind.” New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Cornell, Joseph (1941–42). “Enchanted Wanderer: Excerpt from a Journey Album for Hedy Lamarr.” View 1, no. 9–10.

- Frye, Brian (2001). “Rose Hobart”

- “Joseph Cornell: Shadowplay . . . Eterniday” (2003). New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Lehrman, Robert (2003). “The Magical Worlds of Joseph Cornell” (DVD-ROM). Washington, D.C.: Voyager Foundation.

- McShine, Kynaston (1996). “Joseph Cornell.” New York: Museum of Modern Art.

- Perry, Idris, ed. (1995). “Essays on Dolls.” New York: Viking.

- Rilke, Rainer Maria (1959). “On Dolls.” In “Rilke: Samtliche Werke, vol. 5.” Ed. Ernst Zinn. Insel-Verlag.

- Simic, Charles (1992). “Dime-Store Alchemy.” Hopewell: Ecco Press.

- Sitney, P. Adams (2002). “Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1943–2000.” Oxford: Oxford University Press.