Of Palms and Politics: How Milan's Greenery Sparked a Debate on Italian National Identity

Milan, February 18, 2017 — a few minutes after midnight, flames engulfed a cluster of trees in Piazza del Duomo. Committing arson was a group of nationalist protesters who fled the scene through the semi-deserted piazza, rushing down the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele in the direction of the Scala Theater.

It was all announced a day before, on Facebook, by the neo-fascist group Azione Identitaria (Identitarian Action), who describe themselves as a patriotic and militant cultural movement in defense of Italian, regional, and European identity. The post, widely disseminated online by news outlets, clearly connoted the gesture as political. The aim, as they said, was not to hurt the plants, but to send a clear representational statement — a stark sign in opposition to the “Africanization of Italy.” Milan’s most common trees are deciduous planes, acers, horse chestnuts, poplars, gingkoes, and magnolias — a varied cohort of versatile and mostly non-native varieties imported and established over centuries of botanical conversation with other parts of the world. But it was palms that Azione Identitaria intentionally targeted.

Those familiar with the hustling and bustling northern Italian mini-metropolis might be surprised to hear of palm trees in the first place. Although not indigenous to the Italian peninsula, palm trees have for long been a staple of many southern cityscapes. From Palermo to Naples and Rome, palms are a common sight on lungomare promenades and in public piazzas. But Milan’s cold and dark winters badly suit the needs of these monolithic trees. Despite climatic challenges, a few rare palms have been living in the northern metropolis since the end of the 19th century, most often sheltered in the high-society courtyards of the city’s historic center. I remember, as a child, peering through a corrugated gate to catch a glimpse of their fronds covered in snow; it was as close as real-life could ever get to Fellinian cinematic magic.

However, the palm trees in Piazza del Duomo were a recent addition, planted in 2017 as part of a marketing campaign orchestrated by Starbucks, the ubiquitous American coffee company founded in Seattle at the beginning of the 1970s and today counting more than 38,000 locations worldwide. The 42 palms, along with a grove of 50 banana trees, were intended as a “gift” to the city: a celebration on the occasion of the opening of their first coffee shop in the country.

The exotic grove positioned on the west side of the Piazza del Duomo was the result of a collaboration with Italian architect and urban-green expert Marco Bay. Interviewed soon after the arson, Bay vehemently defended his installation. “The exotic grove was meant to ‘surprise, seduce, and disorient’ and the installation is not permanent,” the architect said. Indeed, the last of the trees are being removed and relocated this year. What Starbucks — and Bay — underestimated was the ability plants have to ignite heated debate on Italian national identity.

Plants, Architecture, and Aesthetic Appropriateness

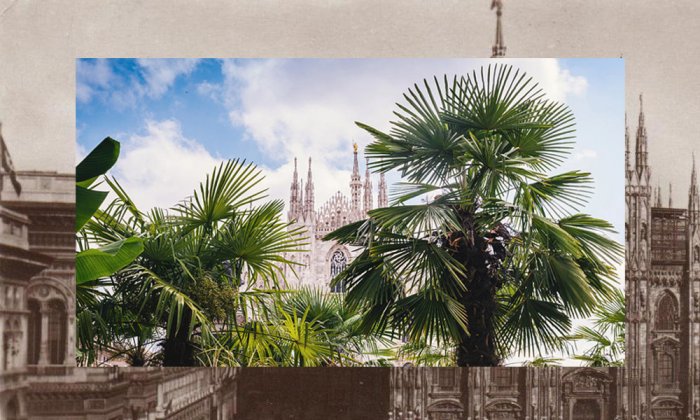

I first learned about these events not from the news, but over a phone call with my parents, who still live in Milan, where I was born. My mother said: “They are planting palm trees in Piazza del Duomo! And bananas too! Everyone’s arguing about it.” I have to admit that my immediate response was of surprise — I struggled to envision how the tropical lushness of palms and banana trees would come into dialogue with the elegantly cold and chiseled façade of the gothic Duomo and the neoclassical architecture of the surrounding buildings. I immediately searched online to find an image; and there it was. Palms and bananas facing the Duomo, lined up like a silent but resilient army. Nature and culture facing each other: the refined spiritual intricacy of pure pale marble confronted by the raw flourishing of exotic trees. For a few moments, I struggled with the aesthetic incongruity.

My mother said: “They are planting palm trees in Piazza del Duomo! And bananas too! Everyone’s arguing about it.”

It was at that very point that I realized something interesting was happening and that I needed to explore in more depth my own reaction to the images. The news of tree-planting in big cities has always brought me joy. But this instance made me realize that I never lingered too long over questions of supposed appropriateness in relation to species and geographical locations — as an immigrant myself, I find “native” a complicated concept since it is haunted by dangerous contradictions and problematic assumptions. But I realized that my initial surprise to the news wasn’t necessarily linked to ecological appropriateness, but aesthetic appropriateness, instead. I began to wonder if the vertical solemnity of cypresses, albeit less exuberant, might have been a better fit for the square’s history and heritage. The cracks in my thinking began to show. I started to notice how my line of reasoning was implicitly frameworked by outdated notions of urbanistic conservation. The feelings were conflicted: I love palm trees and bananas — they remind me of the long summers spent as a child in Calabria, the Italian irredeemable deep south with its bursting flavors, rich traditions, and seemingly insurmountable social problems. So why was I even dwelling over the appropriateness of bananas and palms outside Milan’s beloved cathedral? Where was this feeling that “plants might have been put in the wrong place” originating from?

Milan: History, Architecture, and Identity

Piazzas are essential historical and political constituents of most cities. In the West, more directly, piazzas also are the contemporary incarnation of the Greek agora: the political and commercial heart of the social fabric. In the agora, the athletic, artistic, spiritual, and political life of the city manifested in ways that feed into the formation of a shared social identity. Piazza del Duomo in Milan is no exception. It has a long history of which the city is particularly proud. Its inception dates back to the 14th century and it is intertwined with the prestigious medieval glories of the Visconti dynasty which ruled the city for 170 years (1277–1447). Along with the Sforza, which followed, the Visconti promoted a substantial urban regeneration that promoted the arts to rival the nearby Venice and Florence.

Milan has always suffered from a “second-city” inferiority complex of a sort toward other Italian capitals of culture with deeper histories and more ostentatious artistic beauty. Because of its geographical situation, Milan has also always been a functional crossroad and strategic post. And during the last century, it became Italy’s most powerful industrial capital, gaining a reputation as one of the least culturally interesting and greyest cities in Italy. As such, the Duomo is its crown jewel, a significant historical and architectural achievement that both characterizes the city’s uniqueness from the rest of the peninsula and embodies its distinctiveness. Because of its geographical situation and the range of northern influences it was exposed to, Milan has always fancied itself as almost-French or/and almost-German rather than seeing itself as linked to Rome and Naples.

The construction of the Duomo began in 1386. Rayonnant Gothic, a markedly French architectural style, was chosen to underline the cultural difference between Milan, Venice, and Florence. French engineers Nicolas de Bonaventure and Jean Mignot were in charge of the early construction stages of a project that would take nearly 600 years to conclude, in 1965. For centuries, the rare pink marble of Candoglia, quarried in Piedmont, was shipped to the heart of Milan aboard large barges. For this purpose, Leonardo da Vinci perfected the city’s canal network between 1482 and 1489, designing a complex system of dams and locks that further facilitated commerce.

Toward the end of the 16th century, as a cultural rejection of foreign influences began to emerge, Archbishop Carlo Borromeo turned toward more Renaissance-/Italian-inspired aesthetics. The eclectic result, which elegantly combines Gothic, Romanic, Renaissance, Baroque, and Neo-Gothic, stands as a testament to a persevering city capable of accomplishing impossible feats through means that victoriously bypass any cultural or technological dependency from Rome, the Italian capital Milan has always rivaled. Given its rich history and pronounced emancipatory cultural value for a city that has always looked at Rome with disdain, it is perhaps no surprise that Piazza del Duomo would easily become a neuralgic point for identity-based issues.

Cultural Fragmentation

The negative sentiments revealed by the appearance of palm and banana trees are perhaps best understood in this context, but also in view of the ever-changing cultural shifts that can be mapped around the square itself. As a place for congregation, the piazza has become a point of reference for the many ethnicities that since the late 1970s have arrived in Milan from North Africa, the Philippines, and Eastern Europe. It is not uncommon, especially during the evening hours, to encounter different ethnic groups spending the evening chatting away and drinking in the open air while listening to music. But Italy’s relationship to other ethnicities has recently become more complicated, starting from the common use of the legal-bureaucratic and very discriminatory term extracomunitario. The word, which literally translates into “extracomunitarian,” was originally introduced in the 1980s to designate a subject whose legal standing does not include citizenship to the European Union. However, the term has more generally been used to designate non-white illegal immigrants from Africa and the Middle East.

In time, it has become a popular tool of segregation — it’s a stamp of shame; a major barrier interfering with any possibility to integrate those who are not yet part of the community.

In this context, it is also important to remember that, despite the history of its famous cities, Italy was only unified in 1861. Its past as a fragmentary conglomeration of regions and city-states characterized by extremely different dialects and traditions still shows its cracks.

Could it be that the arrival of the exotic plants in Milan’s beloved piazza has awoken uncomfortable memories of the country’s short-lived colonialist period?

The cultural unification of Italy has effectively been operated by TV networks — the state-run RAI TV, in the first instance, and Berlusconi’s Mediaset, thereafter, during the 1980s. Since the unification, language and customs have erected insurmountable barriers between north and south. The south has been perceived by the north as an underdeveloped and parasitic part of the country. This has led to an internal system of discrimination and hate that eventually produced the Lega Nord political party. Initially ridiculed by many, during the early 1990s, the Lega Nord has relentlessly campaigned for the independence of the North, including economically powerful regions such as Piedmont and Tuscany, and has today also become a Euroskeptic leading voice at the government. In the 2018 elections, the right-wing populist party won 17.4 percent of the vote, becoming the third largest party in Italy.

Representatives of the Lega Nord have been no strangers to racist statements and other discriminatory controversies. In 2013, Cécile Kashetu Kyenge, the first Black government Minister of Integration (2013–14) was publicly likened to an orangutan by a Lega Nord senator. It was therefore not much of a surprise to find delegates of the Lega Nord protesting the palms and bananas with a banner reading “No to the Africanization of Piazza Duomo.” With them, also waving banana-inflatables, were representatives of CasaPound, an openly neo-fascist party currently gaining popularity in Italy. Both groups have unequivocally interpreted the exotic trees as an “invitation to African immigrants,” a sort of welcome statement.

Italy, Colonialism, and Propaganda

Italy’s relationship with immigration has always been complex and contradictory. The waves of emigration that marked the history of the country never seem to play an important cultural role in the contemporary memories of those who object to the arrival of migrants. The Italian diaspora that began with its unification in 1861 has permanently relocated abroad over 25 million citizens, who, in many circumstances, were ghettoized and marginalized in their destination countries. It could as well be that the fraught relationship between Italy and immigration has its roots firmly planted in a nearly forgotten, and yet all-important, chapter of the country’s history. Could it be that the arrival of the exotic plants in Milan’s beloved piazza has awoken uncomfortable memories of the country’s short-lived colonialist period? In 1890, Italy conquered its first colony: Eritrea. Libya was invaded in 1911. In 1936, the conquest of Ethiopia by means of illegal chemical weapons also brought along a set of laws against the “meticciato”: the bastardization of the Italian race. This preventive measure applied to Italian soldiers and civilians in the colonies of Ethiopia and Somalia. New propagandist messages aimed at de-coupling previously incited notions of colonialist and sexual conquest by casting Black women as disease-ridden undesirables. In this context, preserving the presumed purity of the Italian race entailed dissuading soldiers from entertaining sexual relationships with them or committing rape.

It is also at this time that Italian anthropologist Lidio Cipriani, a fascist and a fervent believer in scientific racism, began articulating theories on the inherent inferiority of Black people. In his book “Ethnical Absurdity: The Ethiopian Empire,” Cipriani overtly likened the “Black race” to the state of sub-human animals. Meanwhile, on Italian soil, brothels became subject to stricter racial regulations; and abroad, the government actively began recruiting white, Italian prostitutes (referred to in the official paperwork as “secretaries”) to entertain soldiers in the colonies. The cultural propaganda that conditioned Italians during the 1930s was by no means an isolated case, and it can be better understood in the context of the broader racial discriminations that impacted other nations involved in much broader and more successful colonialist efforts.

Fast-forward to today: Given its geographical location and the absence of a unified European response, Italy finds itself in a vulnerable position within the European Union (EU). In 2023 alone, more than 150,000 refugees and migrants arrived in Italy by sea. (Many will recall the tragic incidents of overcrowded vessels sinking, a problem that sadly persists.) The EU hasn’t exactly been quick to help. This scenario hardly aids racial integration in a country that, more or less, has been defined by a sequence of political and economic crises for over 30 years.

Roots and Fixity

The fixity of plants has often been metaphorically used to visualize the essence of presumed human-fixity: to truly belong to one or another continent or land. To set roots in one place has for long meant to live and develop a coherent life based on a commitment to one’s own local customs and ideals. However, these rhetorical notions of fixity couldn’t be more fictitious when applied to the versatility of real plants; how they can, sometimes very easily, spread across new geographical territories, often adapting to less than congenial climatic conditions. Plants are not static. They travel — in fact, instead of focusing on the fixity of the individual, concentrating on plants’ ability to disperse and migrate might allow us to let go of erroneously naturalized conceptions that only really exist in the markedly human fear of the Other. Simply put, plants are the ultimate migrant.

While far-right innuendos of “Let’s bring in the monkeys” or “Now the Africanization of Milan is complete: Illegal immigrants will finally feel at home” dominated the news, a left-wing group named Sentinelli di Milano (Milan’s Guardians) organized a humorous counter-protest on Palm Sunday. They invited citizens to bring with them “a plant, a fruit, or a vegetable of any form, colour, or provenance to say: we support diversity.” Let’s be clear: Never before in Italian history have botanical species functioned as such charged political catalysts. However, as it happens, phyto-histories are never linear, nor are environmental-human narratives.

Never before in Italian history have botanical species functioned as such charged political catalysts.

The original title of Marco Bay’s palm and bananas installation was “Milanese Tropical Forest.” This was revised by the city government to “Milanese Garden Between XIX and XX Centuries.” The request for a title change is perhaps indicative of an initial sense of unease with the overtly tropical connotation of the project. Instead, the final title justifies (or perhaps dilutes) Bay’s cultural operation as a reference or re-staging of the palm trees that once stood in Piazza del Duomo during the second half of the 19th century.

The ambiguity linked to the title of the installation is further problematized by the complex histories of the species in question. Despite their seemingly naturalized roots, cultural identities can be substantially shaped by rather short but intensely exposed representational constructions. Bananas, for instance, have only become popular in Europe since the 1870s. The plant is not native to Africa, as many might believe, and its long history of domestication spans many ethnic groups from around the world. It is believed that farmers in Papua New Guinea and Southeast Asia first began to select and cultivate banana trees since 600 BCE. Subsequently, Indian traders traveling through Malaysia brought the plant to India, where, in 327 BCE, it was collected by Alexander the Great, who took it back with him to the Western world. Meanwhile, bananas spread to southern regions of China, where different varieties have been selected since 200 BCE. Around 650 BCE, Muslim traders important the plant to Africa and crossbred two varieties, Musa acuminata and the Musa baalbisiana. During the Renaissance, banana trees traveled to Italy for ornamental purposes but were the exclusive possession of the extremely rich; meanwhile, Portuguese sailors discovered bananas in West Africa and established the first banana plantations in the Canary Islands. Thereafter, bananas were exported to Latin America and the Caribbean. The Cavendish variety, which is most commonly available on today’s market, is a crossbred variety engineered in the Duke of Devonshire’s Victorian hothouse, not in Africa. The plant is currently grown across the globe in over 150 countries, from the Caribbean to Central America and South America; to West Africa, the Philippines, and Australia. Since the current edible varieties are seedless cultivars, propagation of plants is only possible through side shoots and roots. This long genealogy technically makes bananas a “transhistorical living sedimentation” of many different peoples and geographies.

Despite its rich and deep history, its univocal connection to Africa in the eyes of contemporary Italians may spring from the country’s colonialist past. Bananas consumed in Italy between the 1930s and the 1950s came from the colonial Italian-Somalia town of Genale, a detail that vastly strengthens the associated racial and geographical connotation that characterizing the fruit in today’s imagery.

The distinctive, straight, and unbranched morphology that characterizes over 2,600 species of palms around the world is today universally recognized as a marketing emblem for the leisure-time paradise. Palms thrive in tropical and subtropical climates around the world; therefore, different species can be found in Southern Asia, South America, Northwest Mexico, and the Arabian Peninsula. The history of their domestication does not begin in Africa either, as records show that early cultivation of palms took place in the Middle East 5,000 years ago. From palm oil to dates, coconut, and raffia for rope-making, palms have provided and still provide substantial sustenance and resources. The palm’s history is also defined by the symbolic values of immortality, triumph, peace, victory, and spirituality — palms are mentioned more than 30 times in the Bible and 22 times in the Quran. In this case, too, the palm is a “transhistorical living sedimentation” of many peoples and geographical realities rather than a specific anchor to a defined notion of national identity.

However, it is likely that the right-wing protesters’ conception of palms overlooks the complex ways different cultures have viewed them throughout history. Not only, in their words, has the tree been reduced to a stereotyped symbolization of the African continent and its people, but the widespread presence of palms in the southern regions from Rome to Palermo makes it the emblem of what right-wing protesters also perceive as an ultimately inferior Italy they would rather separate from. Pejorative comparisons between Italy’s South and Africa have been a frequent recurrence through the rise to power of Lega Nord and have been used in order to support their case for secession.

After seven years, in late February, the banana trees and palms were swiftly removed. It was claimed a parasite damaged most of the plants beyond the point of recovery. The survivors were taken to local greenhouses to be nursed back to health and eventually replanted elsewhere in the city. Perhaps not surprisingly, the new species that will replace them are natives of the alpine landscape — camphor trees, rhododendrons, philadelphus shrubs, typical of the Piedmont Alps, the locality from which the Candoglia marble used to build the cathedral originated. The new planting was ideated by the fashion firm Ermenegildo Zenga whose spokesperson also emphasized the ecological importance of the shift from the exotic predecessors to the local flora. While the replacement of the banana trees and palms might seem like a routine urban renewal effort, it is hard to ignore the timing of this maneuver, just over a year after the instatement of a new far-right government. The new landscaping will most likely raise no eyebrows and ruffle no feathers; it will blend in and become mostly invisible.

The alleged misplacement of plant species has caused an important short-circuiting of intertwined histories of people and plants. It has demonstrated how important plants can be in the politics of identity construction and how they operate in the context of important conceptions like “native” and “other” lurking beneath notions of cultural and aesthetic appropriateness. But most importantly, instances such as these, in which plants become sorely visible, reveal important chains of inferences that, if untangled, might shed light on our everyday relationship with plants, other peoples, and our past and future histories.

Giovanni Aloi is an art historian who teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He is the author of “Why Look at Plants? The Botanical Emergence in Contemporary Art” (Brill) and “Lucian Freud: Herbarium” (Prestel), and the co-editor of “Vegetal Entwinements,” from which this article is adapted.