Waltzmania in the Paris Pleasure Gardens

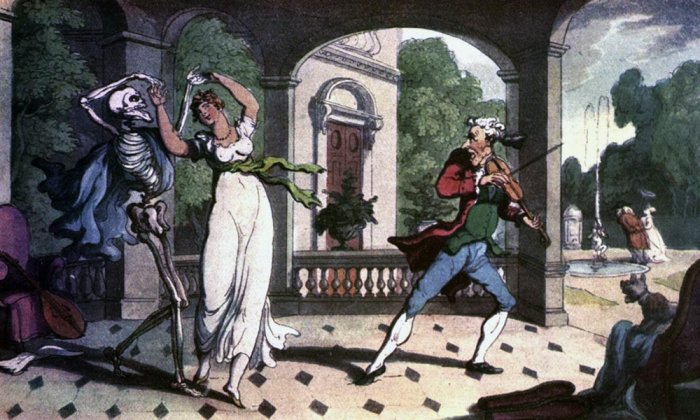

After the violence of the Terror that had marked the French Revolution, when Parisian pleasure gardens multiplied to offer new places of expression for the “frenzy to celebrate” that characterized the “madness of Thermidor,” balls took center stage in the new nocturnal culture transforming Paris. 1 Louis-Sébastien Mercier described dancing as a “universal fury” that had everyone “from rich to poor” twisting about.2 This culture of dancing madness would continue to develop until the Restoration and coincided with the emergence of a (first) romanticism and a new way of imagining the figure of the couple in Europe.

As the 18th-century salon culture of bon mots gave way to the passionate experience of the new social dances, their contagious vertigo became polemical. Under the reign of the Directory, during the winter season of Republican Year VII (1798–1799), the fashionable German “walsces” were all the rage. The first dance with a closed-couple hold to be adopted by an elite society in Europe, waltzing had already created trouble in certain German-speaking regions where it was promptly banned. The acceptance of the waltz in France merely increased concerns. The German poet Ernst Moritz Arndt described the French “nationalization of this German dance” in moralizing terms: The closed-couple hold, he said, allowed the male dancers to squeeze “the lady dancers as close as possible against themselves” while placing their hands “firmly on the breasts” of their partners.3

In this turning dance, the familiar Contredanse figures disappeared as the couple advanced with simple, repetitive steps, improvising their path across the dance floor while negotiating a shared center of gravity. Partners experimented with a vertigo whose centrifugal force and intoxication “exhausted” their bodies and “heated” their imaginations.4 Through touch, the exchange of perspiration, and a rapidity that solicited the imaginations of the dancers embracing one another, the dazzling intimacy of the waltz was said to produce a ravishment that — according to the doctors who described it — menaced the health of an entire generation of youth.5

This “universal fury” of dancing was described according to several medico-philosophical notions: enthusiasm, passion, desire (envie), madness, and a whole ensemble of phenomena connecting body and soul, in which the mental faculty of the imagination played a pivotal role. Mental health medicine (médecine morale) at the time considered that the impressions of the imagination gave way to physical expressions called “nervous sympathies” (sympathies nerveuses) and that these could be transmitted from one individual to another.6 Doctors wrote about the force of the imagination to explain the collective contagion of revolutionary violence: a mental contamination linked to a deviant behavior produced involuntary imitation. Following the same logic, waltzmania was understood as an epidemic of deviant dancing transmitted via the imagination.

Waltzmania was understood as an epidemic of deviant dancing transmitted via the imagination.

The arrival of the German waltz in France coincided with the first publications of the new “Psychological and Political Sciences Class” of the National Institute of France as well as the 1802 creation by the Prefecture of Police of a Council of Hygiene in Paris. In the context of this political dynamic of early hygienism under the French Consulate, waltzmania came to be understood within a genealogy of European choreaic contagions: the 11th-century legend of the Dancers of Kölbigk, Tarantism in Mediterranean Europe, the Veitztanz maligned by Martin Luther and cases of the Danse de St. Guy in Alsace and Rhineland during the Wars of Religion, the Convulsionaries of Saint-Médard in the early 17th century, or even the ecstatic Quaker dances taking place in the North American frontier.

Under the auspices of the new hygienism, the posthumous publication of the heterodox physician Paracelsus, “Les causes des maladies invisible” (1565), had a particular impact on the interpretation of waltzmania. Paracelsus wrote about the 1518 dance epidemic in Strasbourg, reworking his 1537 theory of the cause of dance mania as published in “The Seven Defenses”7: In sum, the imagination strikes the heart and tickles the nerves, and it provokes a turbulent joy and contracts the muscles, inducing the dance. Paracelsus also invented the figure of Frau Troffea, described as having set off the epidemic with her conjugal anger. The phenomenon according to Paracelsus, thus becomes a gendered one, since we are to understand that the chorea lasciva of the Strasbourg epidemic was born from the female imagination. In the eighteenth century, a renewed interest for Paracelsian theories of the imagination followed the very mediatized scandal concerning the medical practices of the Viennese physician Anton Mesmer, who cured Parisian women by touching them in very theatricalized ways (as reported by the Royal Commission in 1784).8 The scandal of Mesmer’s “animal magnetism” reinforced the idea, thereafter widely accepted, that the female imagination was particularly susceptible to contagion provoked by touch and theatrical gesture, that is to say, “nervous sympathies.”

In 1804, P. J. Marie de Saint-Ursin, one of the most prolific physicians to treat the dangers of the new closed-couple dances, published his “L’ami des femmes: Du luxe privé. De la wales” (“A Friend to Women: On Private Luxury. On Waltzing”), a medical text dedicated to Madame Bonaparte and written in a literary prose destined for a female readership. He cites the harmful effects of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel, “The Sorrows of Young Werther,” which begins with a sumptuous waltz shared between Werther and Lotte, and the events of the Revolution that “deformed” young women’s morals in France. Marie de Saint-Ursin describes the waltz as a “battle” of the sexes that, through “the confusion of the senses” and the “degradation of love,” upsets “women’s desires” and destroys the bonds of marriage. As the male dancer embraces the waist of his partner “with a nervous arm,” the couple pivots, “gazes merged, wholly absorbed in one another, they trace a multitude of circles in a state of delirium.” This practice, according to the physician, was responsible for a “general contagion” of dance mania in France.9 Other doctors considered that simply by observing a waltz, the “nervous sympathies” of a young woman could be activated, placing her in a state of contagious mania in which she risked sacrificing her mental health.

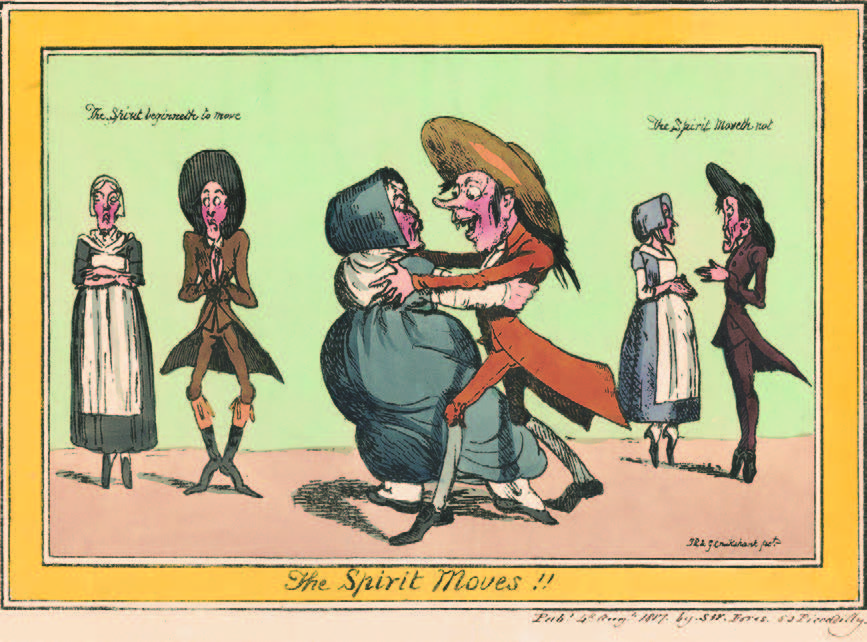

In this political period marked by speculation and the emergence of a new elite, the imperial aristocracy, the academic medical world took a keen interest in health problems stemming from social practices linked to the accumulation of private wealth (“luxe privé”). Urban illnesses like those of the women cured by Mesmer were categorized as nervous diseases specific to the female body. Faced with the excessively passionate dancing fashionable in the Parisian pleasure gardens, the medical establishment, in the interest of public health, alerted families about the potential contagion of the “perpetual” spinning dances that could strike their daughter’s imaginations and induce madness. Doctors and moralists feared the new form of the closed-couple dancing but also the liberalization of the public balls that allowed for unprecedented social diversity within high society exactly at a moment when tensions concerning women’s place in the imperial regime were unresolved.

grotesque little man, obliged to use a handkerchief to achieve the prise-fermée, seems blithely content despite the vulgar gender reversal implied in the couple’s posture: as he gets dragged through the dance by his obese partner, her upturned eyes suggest she is experiencing the jouissance of waltz vertigo. Source: Digital Commonwealth

In this way, the waltz participated in a sociomedical and philosophical debate centered on the powers of the female imagination and the question of republican motherhood, and these tensions were echoed in the specialized press. In the medical lexicon, a connection was established between the vertigo of the waltz and the “exaltation” or “striking” of the female imagination; the contagious character of the dance was correlated to “enthusiasm” or a form of physical and emotional “excess.”10

In the French dance mania, physicians observed the distressed passions of women waltzers and considered this responsible for a “reversal of the natural order of things” and the manufacture of “mannish women” attracted by masculine ambitions.11 They denounced the “very-vexing consequences” brought on by the “exciting and magnetic contact” of waltzing: vertigo, premature menstruation, syncope, spasms, miscarriage, the spitting of blood, tuberculosis, sudden death, clitorimania, and other “false pleasures.”12 These ills contradicted the “pleasures of maternity” that Louis-Jacques Moreau de la Sarthe and other physicians posited as a natural phenomenon.13 If marriage were to serve as a foundational element of modern society, as suggested by the 1804 Civil Code, the exaggerated pleasures of the waltz ran contrary to this recommendation.

In the wake of the Revolution and its fervor, the proper channeling of the collective imagination appeared vital for the successful orchestration and governing of a new imperial “social body.” The public balls remained an ambivalent space in this regard: On the one hand, they were controlled spaces and were monitored by municipal and military forces, yet they also legitimized a framework for the transmission of passionate practices that were susceptible to trouble the social order, especially when it came to gender relations. The circulation of medical discourse on waltzmania had the effect of rendering urgent, in the name of public health, the problem of the involuntary transmission of waltzing and its particular jouissance. The objective was to avoid a moral contagion of the “perpetual dances” that might lead to a collective female mania imprinted with revolutionary republican ideas, that is to say, a chorea lasciva that, by keeping female citizens away from the state-condoned imperative to reproduce, might destabilize the imperial project itself.

Elizabeth Claire is an associate professor of gender history at the CNRS. She teaches the Cultural History of Dance at the EHESS and is currently completing a manuscript on medical theories of the powers of the imagination and social dancing in Europe after the French Revolution. This article is excerpted from the book “Cultures of Contagion.”

Selected Bibliography:

Claire, Elizabeth. “Inscrire le corps révolutionnaire dans la pathologie morale: la valse, le vertige, et l’imagination des femmes.” In Orages: Littérature et culture 1760–1830, no. 12: “Sexes en Révolution” (March 2013): 87–109. http://orages.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/inscrire.pdf.

Claire, Elizabeth. “Monstrous Choreographies: Waltzing, Madness and Miscarriage.” Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture 38 (2009): 199–235.

Goldstein, Jan. “Enthusiasm or Imagination? Eighteenth-Century Smear Words in Comparative National Context.” In Enthusiasm and Enlightenment in Europe, 1650–1850, 29–49. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1998.

Hess, Remi. La Valse, un romantisme révolutionnaire. Paris: Métailié, 2003.

Lécuyer, Bernard P. “L’hygiène en France avant Pasteur 1750–1850.” In Pasteur et la révolution pastorienne, edited by Claire Salomon, 65–139. Paris: Payot, 1986.

Poma, Roberto. “Paracelse et la danse de Saint-Guy.” In 1518, La fièvre de la danse, edited by Cécile Dupeux, 95–114. Strasbourg: Éditions des Musées de Strasbourg, 2018.

Rohmann, Gregor. “Veitstanzähnliche Bewegungen. Dimensionen eines Deutungsmusters zwischen Martin Luther und Ozzy Osbourne.” In Mythen der Vergangenheit. Realität und Fiktion in der Geschichte, edited by Ortwin Pelc, 111–158. Göttingen: V and R Unipress, 2012.

Vermeir, Koen. “Guérir ceux qui croient: Le mesmérisme et l’imagination historique.” In Mesmer et Mesmérismes: Le magnétisme animal en context, edited by Bruno Belhoste and Nicole Edelman, 119–146. Paris: OmniScience, 2015.

Notes:

- Antoine de Baecque, Les nuits parisiennes, XVIIIe–XXIe siècle (Paris: Seuil, 2015), 52–53.

- Louis-S. Mercier, “Les bals d’hyver,” in Le nouveau Paris (Gènes, 1795).

- Ernst M. Arndt, Reisen durch einen Theil Teutschlands, Ungarns, Italiens und Frankreichs in den Jahren 1798 und 1799 (Leipzig: N.p., 1804).

- Christoph W. F. Hufeland, L’Art de prolonger la vie humaine (Lausanne: Hignou en Company, 1809), 217–218 and 320; Samuel A. Tissot, “Des causes morales des maux de nerfs,” Traité des nerfs et de leurs maladies, in Encyclopédie des sciences médicales, vol. 10; Œuvres de Tissot (Paris: N.p., 1840).

- Salomon J. Wolf, Beweis daß das Walzen eine Hauptquelle der Schwäche des Körpers und des Geistes unserer Generation sey (Halle: Johann Christian Hendel, 1799). First published in 1797.

- Pierre J. G. Cabanis, Rapports du physique et du moral de l’homme (Paris: De Crapelet, 1805). First published in 1802.

- Paracelse, Œuvres médicales, éd. Bernard Gorceix (Paris: PUF, 1968).

- The Reports of the Royal Commission of 1784 to Examine on Mesmer’s System of Animal Magnetism and Other Contemporary Documents, new English translation and an introduction by I. M. L. Donaldson, 2014, http://www.rcpe.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/the_royal_commission_on_animal_-_translated_by_iml_donaldson_1.pdf.

- P. J. Marie de Saint-Ursin, L’ami des femmes: Du luxe privé. De la walse (Paris: Barba, 1804), xiii, 49 and 58–68.

- Samuel A. Tissot, “Des causes morales des maux de nerfs,” in Œuvres de Tissot, 126, 130–132, and 367; “Tanzmoden in Breslau, Aus einem Briefe,” Journal des Luxus und der Moden 6 (June 1797): 289–292; Christoph Wilhelm Friederich Hufeland, L’Art de prolonger la vie humaine (Lausanne: Hignou, 1809), 320.

- Jean Etienne Dance, De l’influence des passions sur la santé des femmes (Paris: Didot Jeune, 1811), 15.

- E. Pariset and A. C. L. Villeneuve, “Danse,” in Dictionnaire des sciences médicales, vol. 8 (Paris: Panckoucke, 1814), 1–8; G. J. Raparlier, Dissertation sur le vertige (Paris: Didot Jeune, 1815), 10; Louis-Jacques Moreau de la Sarthe, Histoire naturelle de la femme, vol. 2 (Paris: Duprat and Letellier, 1803), 393–395; Dance, De l’influence des passions, 9; Jean-Joseph de Brieude, Traité de la Phthisie Pulmonaire, par Brieude, Membre de la Société de Médicine de Paris, Membre de la ci-devant Société Royale de Médicine, de l’Académie Royale de Médecine-Pratique de Barcelonne; l’un des Auteurs de la partie médicale de la nouvelle Encyclopédie, book 1 (Paris, Chez Levrault frères, 1803), 32–33; Jean-Joseph de Brieude, “Imagination (Pathologie),” Louis-Charles-Henri Macquart, “Imagination (Hygiène),” in Encyclopédie méthodique. Médecine, contenant: 1° l’hygiène, 2° la pathologie, 3° la séméiotique et la nosologie, 4° la thérapeutique ou matière médicale, 5° la médecine militaire, 6° la médecine vétérinaire, 7° la médecine légale, 8° la jurisprudence de la médecine et de la pharmacie, 9° la biographie médicale, c’est-à-dire, les vies des Médecins célèbres, avec des notices de leurs Ouvrages, book 7, ed. Félix Vicq-d’Azyr (Paris, Vve Agasse, 1798), 465–491, at 471 and 489.

- Moreau de la Sarthe, Histoire naturelle de la femme.