Of Grids and the Great Chicago Fire

One dark night — when people were in bed,

Old Mrs. O’Leary lit a lantern in her shed;

The cow kicked it over, winked its eye and said,

There’ll be a hot time in the old town tonight.

Soon after the Great Chicago Fire burned from October 8 to 10, 1871, this anonymous poem appeared in the Chicago Evening Post. It distills in one stanza, complete with mischievous bovine protagonist, one of our most enduring modern myths. As the story goes, in an unnumbered shed behind the cottage at 137 De Koven Street in Chicago, a hitherto unremarkable cow kicked the lantern lighting her milking. One of five cows in this informal dairy, she normally yielded easily to the patient caress of her udder by practiced hands. But it was hot and dry; there’d only been five inches of rain since July. Maybe Catherine O’Leary’s cowshed was sweltering. Maybe there were too many biting flies in the air. Maybe the normally compliant cow just didn’t want to give it away that day. Whatever the cause, she kicked. Hard.

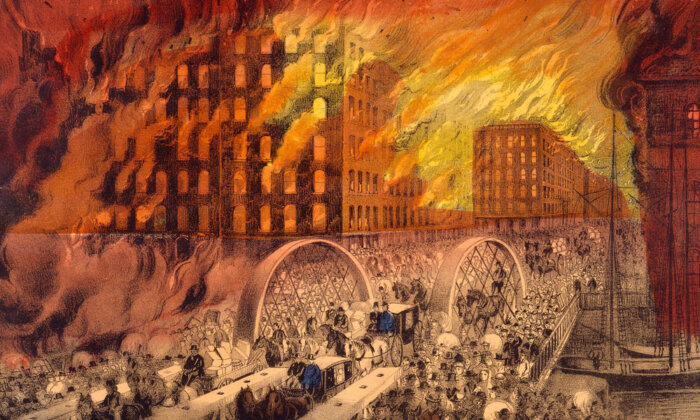

Over went the lamp, sparking a few odd pieces of hay. Mrs. O’Leary stomped them with a worn boot and uttered a few profanities — or so we would imagine. To no avail: More hay caught. Then the floorboards. Outside, the ground itself was tinder. Scraps of leaves ignited. The elevated wooden sidewalk and roadway. Ships along the Chicago River loaded with wood and coal. Buildings. City Hall. The opera. Theaters. The 13-day-old Palmer House Hotel. More buildings. In the end, a third of the city, about 2,000 acres including the entire business district, had burned to the ground. Nearly one-third of the city’s population of 300,000 were homeless.

By this account, history was made in a single animal’s rebellion, rendering mass destruction while also clearing the staging area for a phantasmagoric theater of the future. As the story goes, old Chicago burned to the ground and modern Chicago rose, phoenix-like, from the ashes. The transformation — or at least the impulse for it — was immediate. Two days after the fire, on October 12, Joseph Medill proclaimed in a Chicago Tribune editorial: “Chicago Shall Rise Again.” Within weeks, Potter Palmer secured funding for a new Palmer House Hotel across the street from the first and advertised it as the “World’s First Fireproof Building.”

It comes as no surprise that the modern grid has been at times reviled as a mechanism of dehumanization and at others celebrated as uniquely efficient.

Called shikaakwa by the Miami-Illinois tribe for the skunky smell of the wild-onion that grew on the banks of Lake Michigan, “Chicago” is a French transcription of the earlier name for the area. Founded in 1833, with an initial population of 350, before the fire, it is said, Chicago’s streets curved around the Lake Michigan waterfront and followed the course of the Chicago River and a network of cattle paths lain over Native American migration routes. In contrast to the organic form of the city associated with the early settlers, modern Chicago would be organized as a grid, with address numbers (beginning in 1909) that could tell any pedestrian where they were in relationship to the central point (0,0) of State and Madison streets. According to plan, the modules of this new grid, great skyscrapers, grew up from the rubble like gigantic, up-stretched skeletons of cast iron and, later, steel. The grid, “a framework of spaced parallel bars” according to the Oxford American Dictionary, appears here as the image of an emerging modernity.

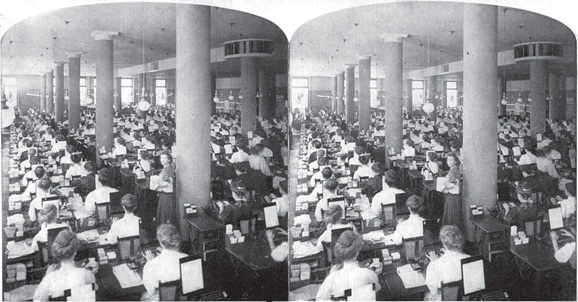

Embedded in this enormous gridded lattice were uniform apartments and office spaces carefully divided into smaller modules of uniform height, width, and length. The offices were filled with supplies delivered in stackable boxes that could be unloaded into standardized desks with little drawers designed to hold gridlike organizers filled with more standardized supplies. A harbinger of long-distance commerce to come, Sears, Roebuck and Co., the mail-order company that shipped goods to the world, was born here. A 1904 picture of Sears’ order-processing room shows how the industrial grid echoes itself at smaller scales that link the city’s gridiron to the office building, then to the manufacturing and distribution process, and finally to the desktop of each worker. Inside this modern factory space, uniformed female office workers labored in a carefully organized grid of identical desks on which stood legions of clipboards — always to the left — with printed order forms snapped to them. The modern work environment is made of such modules, each module the same as the next, each made up of smaller modules adapted to an incorporated whole. Applied with such authority by designers, it comes as no surprise that the modern grid has been at times reviled as a mechanism of dehumanization and at others celebrated as uniquely efficient.

Even today, Chicago sees herself as the quintessentially modern city of industry arisen from an Indian settlement-turned-cowtown-turned-rubble-turned-honeycomb-and-cubical. But the urban grid was operational long before the Chicago fire, long before it was conventionalized as a symbol and product of the modern metropolis and its attendant industrial progress. Most Chicagoans and tourists never learn that Mrs. O’Leary was later acquitted of the dastardly deed, that Daniel “Pegleg” O’Sullivan or another neighbor stepping out from a nearby party possibly started the fire while trying to pilfer some milk, long after Patrick and Catherine O’Leary had gone to sleep. It doesn’t matter that the fire department sounded an alarm that sent the wagons to the wrong neighborhood as the O’Leary fire spread, that several other fires started simultaneously in Chicago on the fateful night perhaps as the result of a meteor shower caused by the breakup of Biela’s Comet, or that the fires spread because the system was already exhausted from a sweep of fires the night before. We certainly don’t learn (or can’t remember) that the city was already laid out on a grid before the fire, though, fatefully, in the flammable materials used during that first wave of development.

We certainly don’t learn (or can’t remember) that the city was already laid out on a grid before the fire, though, fatefully, in the flammable materials used during that first wave of development.

Our oversights are easy enough to explain. The O’Leary story is simply better than these corrective facts. It resonates with an emergence into modernism that is foundational both for Chicago and for American expansion in general. As history, this story offers an emissary of a simpler life, the dairy farmer Catherine O’Leary, whose accident symbolizes the predestined exchange of an agrarian life for one of efficiency and industry. This fiction held sway well before time eroded the facts. Chicago papers published the poetic and factual accounts side by side, as if to suggest their equal merit. The Chicago Evening Journal said as much at the time: “Even if it were an absurd rumor, forty miles wide of the truth, it would be useless to attempt to alter ‘the verdict of history.’ Mrs. O’Leary has made a sworn statement in refutation of the charge, and it is backed by other affidavits; but to little purpose. She is in for it and no mistake. Fame has seized her and appropriated her, name, barn, cows and all.”

The fundamental elements of Mrs. O’Leary’s story, in which nature-fated destruction virtually necessitates emergence into the grids of industrial life, is repeated in the genealogy of many cities.

The destruction occurs by warfare with the Dutch in New York, by earthquake in San Francisco, and by revolutionary agitation in Paris. In each of these instances, the grid plan takes over in apparent opposition to nature, including human nature, whose form is irregular and inefficient. Ever since these early, apparently wholesale transformations, the interconnected, nature-subsuming grids of the emerging modern metropolis have proven themselves infinitely appealing and adaptable, guiding the creations of not only city planners and architects but artists and designers throughout the 20th century and into the 21st. Coupling this application of grids with the O’Leary story and stories like it, one could even argue that the grid is the dominant mythological form of modern life — a visualization of modernity’s faith in rational thought and industrial progress comprising everything from the urban landscape to the power grid, from modernist painting to the forms of modern physics.

The tale of Mrs. O’Leary demonstrates the persistence of premodern grids. At the outset of the fire, our much-maligned beast stood in a cowshed, the simplest of buildings, a single module in an irregular grid that included other buildings. The grid existed in the long, skinny plot that housed Mrs. O’Leary’s cottage and shed and in the maps that brought Irish Catholic immigrants like her to America. The grid was there in every hymnal with musical notation, in the ledger books in every shop she entered, every printed sign she encountered, every newspaper she read or didn’t read. The grid existed in the surface of every brick wall and every building facade dotted with regularly spaced windows and their panes.

The persistence of grids demonstrates that once a grid is invented, it never disappears. At least not yet. Neither does the grid evolve in isolation. Rather, the quality of each grid progressing to the next ties them to political, social, economic, and religious histories, each grid aligning with a different universalizing scheme. Large-scale urban planning follows on the invention of the grid plan and reflects the expanding scope of the Egyptian bureaucracy. Vast territorial conquest requires maps, which appear during the reign of Alexander the Great and signify expanded imperial power. Orchestral performance is inextricably bound up with the invention of musical notation and the spread of Roman Catholicism. Mass literacy is unimaginable without moveable type and reflects the literacy required by a newly emergent merchant class in the early modern period. Each of these grids scales information, whether domestic, geographic, musical, or textual, and on behalf of its user, by turns a bureaucracy, an empire, a church, and the emerging merchant class.

Made by human hands, grids are endowed with a most human contradiction: a vigorous free spirit and a propensity to control.

The history of the grid is a living history of crafted things — from the handmade object to the World Wide Web. Made by human hands, grids are endowed with a most human contradiction: a vigorous free spirit and a propensity to control. And what of the habitual hands of Mrs. O’Leary? Her servants pulled the udder, which riled the cow, which kicked the lantern, which started the fire, which nearly sealed the fate of the grid. But merely nearly. That mythical creature, the grid, was ready with the aid of builders to leap from the ashes — leaner, meaner, and stronger than ever before. But not everlasting. The few scraps that remained of Mrs. O’Leary’s farm were torn down in 1956 to make space for the new Chicago Fire Academy. Here, fires are forever set and doused by aspiring firemen and women, a fitting reminder of the grid’s constant making and unmaking. There’ll be a hot time in the old town — tonight and every night.

Hannah B Higgins is professor and founding director of the IDEAS program in the School of Art and Art History at the University of Illinois, Chicago. She is co-editor of “Mainframe Experimentalism” and the author of “Fluxus Experience” and “The Grid Book,” from which this article is adapted.