A Complete History of Collecting and Imitating Birdsong

Since literature began, poets and naturalists have coined words and phrases which attempt to replicate the sounds birds make. Their legacy is a glorious vocabulary of thousands of unique words, from the aaaaw of the black skimmer to the zzzzzd of the lazuli bunting. A muddled, contentious, and inconsistent vocabulary, the harvest of the jottings of different naturalists in different places, who hear differently and record differently, whose variation is boundless and consensus occasional: Their liberty and ours to spell the “words” of birds as promiscuously as the Elizabethans spelled the spoken word. Twenty-five years ago I sought for the first time to collect, sift, and standardize these wonderful, bizarre words with their anarchic spellings, absurd pronunciations, and uncertain meanings. That project culminated in “Aaaaw to Zzzzzd: The Words of Birds,” the appendice to which is featured below. Here, we see the history of alternative attempts to collect bird songs and sounds, from musical composition through recording devices to duck calls, bird organs, singing bird automata, and varieties of bird clock.

Field Recording

Contemporary field guides to birdsong are commonly audio books accompanied by CDs of birds performing in the wild. Their great advantages over verbal notation are veracity and lack of ambiguity; their disadvantages that they record the particular rather than the general, and have no mnemonic expedient. Collecting and recording bird sounds is more popular than ever, with the development of affordable, high-quality recording and archiving equipment, while improving technology and resources have resulted in birdsong being frequently sampled in contemporary music.

The earliest known bird recording, of a captive Indian shama at the Frankfurt Zoo, was made in 1889 by the godfather of bird recording, Ludwig Koch, then aged eight years old. It was cut on the first retailed recording device, the Edison cylinder machine, which focused the sound through a horn onto a stylus, whose vibrations cut a groove into the surface of a wax cylinder revolving at a speed of 160 rotations per minute (rpm). The cylinders, whose recording time was limited to around two minutes, were played back on the same machine. The Edison was used by Dr. Sylvester D. Judd in 1898 to play recorded birdsong to an academic audience for the first time ever at the 16th Congress of the American Ornithologists’ Union in Washington, D.C., and also for the first recordings of wild birds, at Kenley, England, in 1900, when Cherry Kearton captured the songs of the nightingale and song thrush. The machine had to be positioned close to the subject, and it was found that the noise of the stylus cutting the wax tended to disturb the bird and curtail the song.

The first gramophone record of a bird singing was issued in England in 1910, a 10-inch, 78 rpm disc featuring a nightingale recorded by Karl Reich in Berlin. The technique for this method of field recording was refined by 1926 with the introduction of the electrical microphone, positioned and camouflaged close to where the subject was expected to vocalize. Cables were run to the recording plant, a cumbersome machine that would be located up to a mile from the microphone, where the operator would monitor the signal through headphones or a small speaker. At the chosen moment the cutting stylus was lowered onto the recording medium, a wax disc or, later, an aluminum disc with a pressure-sensitive acetate coating, revolving at 78 rpm. Ludwig Koch headed a team traveling extensively in England in the 1930s, with a mobile recording studio equipped with three recorders and five microphones; he edited the results into the first popular birdsong audio books, “Songs of Wild Birds” and “More Songs of Wild Birds.” The Ludwig Koch archives became the foundation of the BBC Natural History Unit’s Sound Library, and his collection is now housed in the National Sound Archive at the British Library.

Field recording was greatly improved with the advent of the parabolic reflector, pioneered by Peter Keane and Arthur A. Allen of Cornell University in 1932. This enables sound to be collected accurately from a distance of scores, or even hundreds, of yards, by reflecting the sound off a directional dish receptor onto a microphone positioned at the sonic focus, rather in the manner of a contemporary satellite dish. For best results the reflector is hand-held, and an assistant operates the recording equipment. The alternative is the shotgun mike, which has the microphone diaphragm situated at the base of a long tube, making for a very directionally sensitive, if rather short-range, sound collector.

Bird sound has also been captured using motion picture equipment, the first occasion in North America occurring on May 18, 1929, when Arthur A. Allen and Peter Paul Kellogg recorded the song sparrow, rose-breasted grosbeak, and house wren at Ithaca, New York, on synchronized movie and audio film. The recordings of Kellogg and Allen formed the basis of what would become the Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds, at Cornell University.

Situations can sometimes demand that recordings be made via radio transmission, a portable transmitter in the field broadcasting the signal to a radio receiver connected to a recorder. This was an obvious advantage in remote and hostile locations at a time when recording equipment was bulky and heavy. The technique was tried for the first time on December 3, 1934 in the Antarctic, when an emperor penguin was recorded via a radio link onto aluminum disc. The reel-to-reel tape recorder using magnetic tape was first used for recording birds by Sture Palmér in Sweden in 1946, when guillemots and razorbills on the island of Gotland were the subject. High- quality, reliable, portable machines, notably the Uher and Nagra decks, became available in the 1960s and were the standard apparatus for several decades, enabling longer recording times and easier editing. The first stereophonic bird record, a 7-inch, 45 rpm EP, “Birds in Stereo,” was recorded in Sweden by Sten Wahlström and Sven Åberg and released in 1963.

DAT (digital audio tape) recording became available in the 1980s and offered the advantages of low self-noise and an extended frequency response. Analog cassette, digital compact cassette, and MiniDisc systems have all been put to purpose, while the current generation has full digital hard disk/Flash capability. As well as greater portability and a new level of recording brilliance, these latest systems offer greater ease in editing, analyzing, sharing, and storing recorded material. By 1965 around 25 percent of the 10,000-odd bird species known worldwide had been recorded, increasing to 50 percent by 1982. The figure today stands at greater than 90 percent. A major resource is the British Library Sound Archive in London, which houses historical, commercial, and private field recordings covering more than 80 percent of world species.

An important spinoff has been that some species thought to be extinct have been rediscovered by the recognition by their recorded sounds. These include the Puerto Rican whip-poor-will in 1961 and the orange-fronted parakeet, identified in the D’Urville Valley, New Zealand, in 1965.

Graphic Notation

Before the advent of recording equipment, birdsong could most readily be captured on paper. Phonetic transcription — “bird words” — was one method; the other was to use a system of symbolic marks. The earliest of the graphic systems was the adaptation of the existing convention of musical notation.

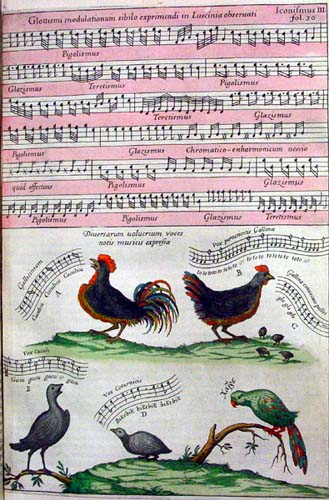

The first scholar known to have written bird sound in this way was the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher, described by historian Robert Irwin as “one of the last scholars aspiring to know everything,” inventor of those antidotes to birdsong, the megaphone and the cat piano, and author of the “Musurgia universalis” (1650), whose premise that there was a harmonic relationship between music and the planets was illustrated with notation of birdsong. Sight-reading ornithologists find it an effective shorthand, though there are disadvantages: Musical notation tends to simplify (although the same could be said of transcription); bird notations rehearsed on musical instruments become so approximate as to be often unidentifiable; not everyone can read music. And as the zoologist Walter Garstang has pointed out, tune is the least part of the performance of species such as the skylark.

The author and bird watcher Aretas A. Saunders made the further proposition that notation is unsuited to birdsong since birds make use of musical intervals not capable of indication in our system of music. His belief that attempts at representation by words from human speech or by musical notation had been, with exceptions, “almost total failures” led to his invention of a unique graphic system. This was introduced in “A Guide to Bird Songs,” first published in 1935 and demonstrating the songs of more than 200 eastern U.S. birds. Saunders’s notation is a score sitting within three bands. The upper band contains a description of musical quality, such as “melodious,” “harsh rattle,” etc. The line of the song is conveyed in a phonetic transcription in the lowest band. The reading of this is modified by the graphic score in the middle band, comprising hieroglyphs representing the articulation of the individual notes, with a horizontal element indicating duration, of a thickness indicating volume, at a station within the band indicating pitch. Vertical lines indicate connected notes. A “key signature” to the left of the score shows pitch at that position.

The Saunders notation adds to our ability to reconstruct birdsong inside our own heads, given practice, but remains the Saunders notation, not the birdwatchers’ notation. This is a pity, as Saunders came closer than anyone to devising a method of collecting birdsong using pencil and paper alone. Perhaps we find his method underintuitive; or perhaps we have an aesthetic aversion to a technique akin to capturing the sound of, say, a Chopin prelude in a diagram resembling less the lines of the music than of the inside of the piano.

The invention that has given us a real new insight into the structure of birdsong is the sonograph. This recording device plots sound frequency against time, tracking the results with a pen on a revolving roll of paper to produce a sonogram. This shows the acoustic spectrum of each sound, enabling analysis of pitch, timbre, quality of tone, and overall structure. The sonograph was developed as a forensic tool at Bell Telephone Laboratories in New Jersey in the 1940s, and its potential for research in his own field of expertise was quickly grasped by W. H. Thorpe, professor of zoology at Cambridge.

Sonograms have a graphic presence that gives us a “feel” for the sound they convey, and may be intriguing and even beautiful to look at, but their proper interpretation is not intuitive, and they remain more a tool of the researcher than of the birder.

Thorpe’s experiments with the sonograph from 1949 have trailblazed its use in the scientific analysis of animal sounds. They revealed for the first time how birdsong may range from a simple, linear melodic line, through songs of greater complexity displayed as calligraphic curves and spikes and bands of black ink, to those showing two or even three simultaneous melodic lines, as hard to discern by the ear alone as they are to convey other than by sonographic means. Sonograms have a graphic presence that gives us a “feel” for the sound they convey, and may be intriguing and even beautiful to look at, but their proper interpretation is not intuitive, and they remain more a tool of the researcher than of the birder. Despite attempts to include sonograms in field guides as a “score” to be used in conjunction with either field recording or notation, their value in bird books is for the most part as a curiosity.

Birdsong in Music

There are a number of ways in which bird music and human music may overlap or interact. The most general and widespread occurs when composers are simply influenced or inspired by birdsong, the precise nature of the individual song often being sublimated or varied, and the composition not attempting any true reproduction of specific bird sound. A master of this was Richard Wagner, who reconstituted the birdsong of Bavaria into a cast of warblers and wood birds that are part real, part mythological.

The imitation of birdsong by musical instruments or voices is probably as old as music itself. One of the oldest surviving pieces of music from Britain is the 13th-century “Sumer is icumen in,” in which we hear the song of the cuckoo, “cuccu cuccu, wel singes thu cuccu.” The unmistakable motif of the cuckoo, shorthand for the onset of summer, recurs across the centuries in pastorals by composers from Handel to Beethoven, through Mahler and Frederick Delius, to Michael Tippett and György Ligeti. Nightingales are heard in Rameau, Scarlatti, Handel, Schubert, and Rossini, while the songs of doves, linnets, canaries, larks, and warblers are among others most frequently heard in the concert hall. A cock crows thrice in Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion”; swans beat the skies of Grieg and Tchaikovsky.

The unmistakable motif of the cuckoo, shorthand for the onset of summer, recurs across the centuries in pastorals by composers from Handel to Beethoven, through Mahler and Frederick Delius, to Michael Tippett and György Ligeti.

The songs of different species of birds make a natural subject for musical suites, including Clément Janequin’s “Le chant des oiseaux” (1529), which has been described as a “cacophonous chanson”; Camille Saint-Saëns’s “Le carnaval des animaux” (1886); and the broad selection of birdsong featured in Luigi Boccherini’s string quartet “The Aviary” (1771). These occasional compositions are somewhat dwarfed by the opus of 20th-century French composer Olivier Messiaen, whose lifelong interest in ornithology and birdsong informed and inspired his musical composition with an unparalleled knowledge and passion. For Messiaen, birds were the symbol of freedom, and their song the symbol of true musical expression, with its unaffected craftsmanship and improvisation. His “birdsong” techniques, which acknowledge not only the song of the bird but the season, the place, and local color, first appear in “Quatuor pour la fin du temps” (1941), and are developed most tellingly in “Réveil des oiseaux” (1953) and the set of pieces for solo piano, “Catalogue d’oiseaux” (1958).

The vocal imitation of birds, by singing or whistling, has its own virtuosi. The first commercial disc of a human imitation of a bird call was George W. Johnson’s “The Mocking Bird,” released in America in 1896. One of the best- known British imitators was Percy Edwards, a broadcaster and entertainer who happened to be a published ornithologist. His 60-year career began on BBC radio in 1930, and he became a household name for his bird and animal imitations, developing a repertoire of several hundred species of birds. More recently Nicole Peretta,“The Bird Call Lady,” has appeared on U.S. television and recorded on CD some of her imitations of more than 150 species, vocalized without whistling. The Festival of the Osei, a market exhibition of songbirds and aviary held annually at Sacile in Italy since 1274, features a songbird imitator competition. The embedding of actual recordings of birdsong became feasible in the early twentieth century, a pioneering example being “The Pines of Rome,” written in 1923–1924 by Ottorino Respighi, whose score incorporates a gramophone record of a nightingale (in live performance this part may be taken by a human imitator). Johan Dalgas Frisch set a tape of birdsong from Brazil to orchestral accompaniment in his “Sinfonia das aves brasileiras” (1966). In 1972 the Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara wrote “Cantus arcticus,” sometimes called “Concerto for Birds and Orchestra,” an orchestral piece incorporating prerecorded bird songs and calls, such as those of migrating swans, from the Arctic.

Compositions created in the studio, by layering recorded bird sounds, include the American composer James Fassett’s “Symphony of Birds” (1955) and the last work of Karl-Birger Blomdahl, a composition for Swedish radio entitled “Altisonans” (1966), which combines bird sounds with other recorded sounds from nature and radio emissions from satellites.

One final type of interaction is to make music with the intention of provoking or affecting birds. A mechanical device for encouraging cage birds to sing, the serinette, is considered elsewhere. The slightly more eccentric notion of playing with the birds, en plein air, has had some recorded triumphs, including a 1920s BBC radio broadcast of cellist Beatrice Harrison successfully encouraging nightingales in a Surrey wood to sing by playing popular cello pieces to them. More recently David Rothenberg has recounted, in “Why Birds Sing,” his experiments with Michael Pestel in interacting with singing birds by making sounds that are part imitation, part improvisation, using clarinets, saxophones, flutes, whistles, and bird calls. We might be reminded of Saint Francis of Assisi who, it was said, spent a whole night singing alternately with a nightingale, finally conceding victory to the bird.

Whistles and Imitators

The English mind turns every abstraction it can receive into a portable

utensil.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson

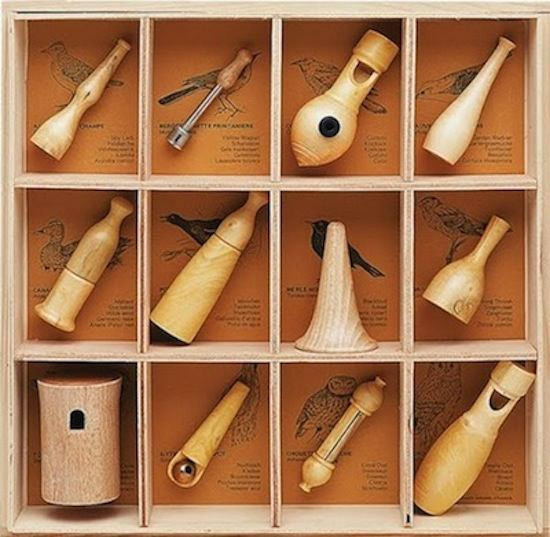

Bird whistles, or imitators, fulfill a number of different purposes: to attract and locate birds for hunting and wildfowling; as an aid to birdwatching; as ornaments; and as toys and entertainments. The earliest hunters’ whistles would have been crude devices cut from reed or bamboo. They evolved in many parts of the world, notably the Amazon and China. The Romans made theirs of terracotta. Modern calls have hardwood, plastic, acrylic, or brass bodies, and are used in gamekeeping, to call crows and magpies, and in field sport to call ducks.

The commonest type of game or duck call is played like a recorder, by blowing air over a single or double reed and through a resonating chamber. Instruments are usually shaped like horns or whistles, and vary widely in proportions depending on the sound required. Some have a bladder to propel the air, particularly useful when the movement of the whistle to the player’s lips may alarm the bird, or a bellows which operates when the call is shaken, reproducing the chattering sound of ducks or geese feeding. Wooden calls give the lowest pitch, a rounded, warm tone, and produce least volume, while acrylic has the highest pitch and volume, useful for calling ducks over large expanses of water. Plastic calls are pitched somewhere between the two. Some are blown “clean,” others require a blown grunt to achieve the full effect.

Birdwatchers use a wider range of calls to attract otherwise elusive species and to stimulate the songs of garden birds. The nightingale call is worked by twisting a key in a barrel to mimic the rapid “ratcheting” element of the song. A slide, or swanee, whistle can be used to imitate various bird songs in the right hands. Pea whistles recreate some of the higher-pitched calls, while a warbling effect is attainable by blowing the air through a reservoir partly filled with water (whistles of this type were used to mimic birdsong in Elizabethan theater).

In England, ornamental bird whistles were mass-produced in the 19th century, usually in the form of a dovelike bird with blue, brown, or green glazes, and were sometimes put inside chimneys to ward off evil spirits.

Ornamental bird whistles, usually ceramic, have a cultural niche of their own. In England they were mass-produced in the 19th century by Whieldon of Staffordshire, usually in the form of a dovelike bird with blue, brown, or green glazes, and were sometimes put inside chimneys to ward off evil spirits. Italian ceramic whistles (fischietti) have a centuries-long popularity, and were often given as love tokens. A huge collection of Italian and other examples is housed at the Museo dei Cuchi in Cesuna di Roana, in the province of Vicenza, and there is even a whistle festival or Sagra del Fischietto Popolare held annually in Canove di Roana. Because they are cheap, reasonably durable, and fun to play, bird calls have always doubled as children’s toys. Several may be heard in Leopold Mozart’s madly entertaining “Toy Symphony.” The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds offers a range of fluffy toy birds that produce an authentic call when squeezed.

Bird Organs and Tutors

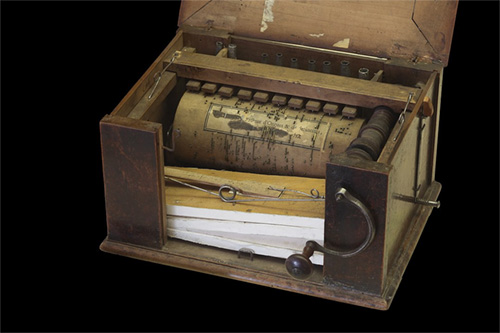

Bird organs, also known as serinettes, make a sound similar to that of the piccolo, and were intended for ladies to teach their singing birds (“serins,” or finches) to sing human compositions. They appear in eastern France at the beginning of the 18th century, their manufacture being centered on Mirecourt in Lorraine. Construction was remarkably consistent, with little variation between different makers or across the 100-odd years of their manufacture.

The typical serinette is a barrel organ with one or two ranks of 10 metal pipes, housed in a wooden case of walnut or beechwood, often inlaid with marquetry and having typical dimensions of around 11 by 8 by 6 inches. Turning a crank mounted on the front of the case pumps the bellows supplying air to the pipes, and also turns a wooden barrel by means of gears. Driven into the barrel are brass pins and staples encoding the tunes. As the barrel is turned, the pins and staples lift wooden keys, operating push rods which open the pipe valves, admitting air into the organ pipes. Tunes, which last about 20 seconds, are ornamental in arrangement and chosen for their quick tempo. To change the tune, the key mechanism is lifted and the barrel slid along its length into a different locked position. A barrel may carry four or eight different tunes, and the repertoire may be increased by having a stock of barrels, which are easy to lift out and replace.

The serinette in deployment may be seen in a 1751 painting by Jean- Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. An affectionate study of luxury in idleness, “The Bird Organ,” or “A Woman Varying Her Pleasures” hangs in the Louvre, Paris.

Serinettes would no doubt have been effective if used systematically. Joseph Walter Belmont, who trained canaries in the 1930s, advised that a real singing bird must start his career at eight weeks, by being shut in a dark room and taught to imitate a master canary, a human whistle, or some musical instrument. Promising performers should be given practice three hours a day, and should have developed a full repertoire by the end of a year. Contemporary with the serinette, the much less ornate bird flageolet was a small high-pitched recorder, made of wood or ivory, which found popularity in England, Germany, and France.

A collection of tunes for different species to be played on the instrument was published in London in 1717 with the title “The Bird Fancyer’s Delight.” A century and a half later Arthur Lloyd, the Victorian music hall singer, wrote a song called “The Bird Whistle Man,” whose sheet music is illustrated with a drawing of a man selling “New Chinese Bird Whistles for the Tuition of Birds”:

So don’t think me absurd

And believe me when I say

I’ll teach your little bird

To whistle night and day

A latter-day Bird Fancyer’s Delight is The Whistler’s “Whistling Workout for Birds,” a series of CDs intended to train birds in the skills of whistling. Produced by Rob “the Whistler” Stemmons, of Oklahoma, they offer selections of short whistled melodies interspersed with one-minute “practice time” silences, and are intended to offer birds a model of excellence to emulate.

A modern novelty variation is the construct-it-yourself Gakken’s Bird Song Organ, operated by scrolling a hand-made punch card past the organ pipes, the punch holes admitting air to the pipe valves creating “your own hand-cranked chirping cacophonies,” unlikely to resemble anything found in nature.

Singing Automata and Clocks

We like the sound of birds in and around our houses so much that we have kept songbirds in cages for centuries. And if we can’t stand the bother but enjoy the song on demand, we can buy (for rather more than the cost of a caged bird) a singing bird automaton. Such was the reasoning of its inventor, Pierre Jaquet-Droz, a theology student who converted to the study of horology.

His earliest singing bird box, which had a pipe organ producing the birdsong, was made at La Chaux-de-Fonds in Switzerland in 1768. Jaquet-Droz replaced the pipe organ with a refined clockwork mechanism, with a tiny leather bellows and automated piston whistle assembly operated by a set of six or eight shifting revolving cams, the prototype for all birdsong automata. His invention, fancy and romantic as it was, captured the spirit of the times and became a Europe-wide success. Jaquet-Droz founded an international partnership, which later included his son, to meet the demand.

The configuration of the earliest automata was based on an ornate tabatière or snuffbox, in copper, brass, or silverwork, tooled and engraved, sometimes enameled or with an inlay of semiprecious jewels. A knob released a spring catch, opening the lid. A bird popped up and performed in solo, singing for up to ninety seconds. The robotic movement, activated by clockwork propelled cams and pulleys, might include the bird revolving on its support, opening and shutting the lower beak, moving the head from side to side, flapping the wings, and fluttering the tail. The birds had papier-mâché bodies dressed with dyed feathers, and bead or jewel eyes.

A significant improvement in sound authenticity came in the early 1800s, through the development by Jacob Frisard of an arrangement of the cam sets used to produce the birdsong in a continuous spiral, so that no break occurred from the beginning to the end of the melodic warble. The Jaquet-Droz sound mechanism was perfected in 1848 by Blaise Bontems in Paris, whose device enables an intricate melody with precise articulation, vibrato, and melismatic lines, simulating real birdsong in a plausible if approximate rendition.

Bontems was also responsible for a more realistic configuration, a cage with anything from two to a dozen or more life-size birds perching in foliage and singing to each other. He exhibited his unique automata at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, and his Paris-based family business continued manufacturing bird automata until 1956. The company was bought by Reuge of Sainte-Croix, Switzerland, who continue the business to this day.

In Germany, Karl Griesbaum solved some of the problems of the original box design in 1905, when he added safeguards including a slow-closing lid and a device that prevented damage to the mechanism should the lid be closed during its play. Music boxes to the Griesbaum 1905 standard are still being hand-made in the Black Forest today. Other configurations include the Rochat singing bird bouquets, in which a small flock of up to eight birds perches in an arrangement of silk flowers, with the mechanism concealed in the vase. This has been latterly revived by the manufacturers MMM/Symphonion. And perhaps it is no surprise that Fabergé have produced a limited-edition, hand-painted, 24-karat-gold-encrusted Limoges porcelain egg, opening to reveal a miniature Reuge singing bird in a gilded cage.

An extensive collection of bird automata and other kinds of mechanical musical instruments, built up by automaton collector, restorer, and maker Siegfried Wendel, is on display at Siegfrieds Mechanisches Musikkabinett at Rüdesheim am Rhein, Germany. The original bird clock, the cuckoo clock, has its origins in the 17th century, and has been produced in the Black Forest, Germany, since the mid-18th century. Arguably the most persistently ridiculed object in the history of home furnishing, the typical cuckoo clock is pendulum-driven and occupies a wooden case in the form of a rusticated hut or chalet, often decorated with carved animals and foliage. On the hour a gong strikes, a trapdoor opens, and a cuckoo automaton springs out. The cuckoo call is made with a small bellows driving an organ with two pipes. More elaborate models may include a music box playing a tune on the hour, and additional sylvan animations. Quartz battery-powered cuckoo clocks replace the pipe organ with a digital recording of a cuckoo in the wild, usually with an echo, other birdsong, and the sound of a waterfall. The striking gong is omitted. Contemporary bird clocks have a conventional clock format with a face diameter of eight to fourteen inches. They play recordings, lasting around twelve seconds each, of the songs or calls of twelve species (typically North American garden birds), one for every hour, with a captioned image of each decorating the clock face at the relevant hour. A light sensor silences the chimes in darkness, allowing the birds, and us, a welcome interlude.

Footnote

Gratifyingly, some of the earliest bird machines have been given a new lease of life. A fantasy of birdsong mechanisms playing in unison may be heard in Aleksander Kolkowski’s baroque performance piece “Mechanical Landscape with Bird,” commissioned by the MaerzMusik Festival–Berliner Festspiele and premiered on March 28, 2004 at the Sophiensaele, Berlin.

On a revolving carousel a string quartet plays canary tunes on the Stroh violin, an instrument used for the first quarter of the 20th century for sound recording, and characterized by a large aluminum trumpet horn. A serinette in a perspex box plays a composition based on the song of the waterslager canary, stimulating into song eight singing canaries nearby. The song is recorded, and played back, on a pair of Edison wax cylinder machines, the faintness and fragility of the recorded sound, concealed within a patina of surface noise, being likened by the composer to an aging process through which we strain to hear the past.

John Bevis is a writer, poet, and book artist living in London, and the author of “Aaaaw to zzzzzd: The Words of Birds,” from which this article was excerpted. He can be found at johnbevis.com