The Eldritch Roots of Dungeons & Dragons: Jon Peterson and Peter Bebergal In Conversation

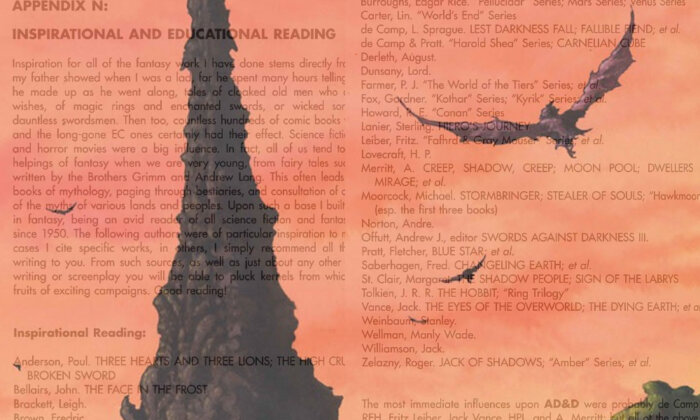

There’s a short section — not even a page long — in the back of the 1979 “Dungeon Master’s Guide” in which Dungeons & Dragons co-creator Gary Gygax includes a list of “inspirational and educational reading.” This section, says Peter Bebergal, a cultural critic known for his writings on speculative and fringe cultures, provides an important window into Gygax’s mind and functions “sort of like the DNA of his thinking about what fantasy was and how to make worlds.”

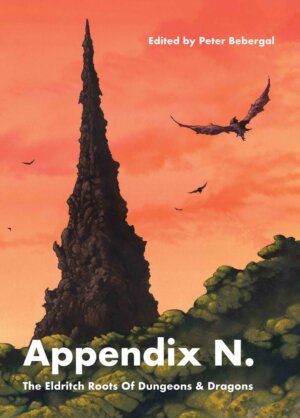

Drawing upon this original list, as well as hobbyist magazines and related periodicals, Bebergal’s new book “Appendix N” offers a collection of short fiction and resonant fragments that reveal the literary influences that shaped and defined Dungeons & Dragons. The stories gathered in the book contextualize the ambitious lyrical excursions that helped set the adventurous dungeon-crawling atmospheres of fantasy roleplay as we know it today.

In the following discussion with Jon Peterson, a widely-recognized authority on the history of games and the author of numerous books on D&D, Bebergal explores some of these influences and discusses the process of editing the collection.

A stream and shortened transcript of the conversation, originally recorded in February 2021 for the MIT Press podcast, can be found below. You can also listen to the discussion on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

Jon Peterson: Peter, thanks so much for coming on. I’m a fan of your work and it’s really great to meet you and be talking to you about something that we both love very much. Can you tell us a bit about Appendix N?

Peter Bebergal: Thank you, I’m a fan of your work and it’s great to meet you. Appendix N is an appendix from “The Advanced Dungeons and Dragons: Dungeon Masters Guide,” which was published in 1979. It’s a section that Gary Gygax, the author, calls the inspirational and educational reading list. He proposes this appendix (which doesn’t even take up a whole page in the book) is his attempt to show new players the kinds of literary influences on him while writing the guide and how they shaped the look and feel of Dungeons and Dragons. I like to think of it as just a window into the mind of Gary Gygax as a game designer.

JP: Definitely. There may be people who are listening to this who aren’t familiar with the kinds of stories you find yourself in when playing D&D. Maybe that would be an interesting place for us to start exploring. What do you see as the life or the arc of a typical Dungeon adventure? What do you think are the common kinds of stories we end up telling with D&D?

PB: For people who are playing D&D for the first time now via the more recent editions of rules, it’s a little different to the game that Gygax describes in the “Dungeon Masters Guide” in 1979. The ’79 guide is more of a fantasy sandbox. Whereas, I think, the more recent editions are more prescriptive.

But with that being said, the core of a D&D story is usually some form of heroic adventurer on a quest. You’re often given a puzzle to solve, someone to rescue, a monster to stop, or a treasure to find. These adventures are likely to take place in some kind of dungeon or lost temple, some kind of underground structure. When you look at D&D you see that the game play is very local. It’s focused on a place, if that makes sense?

What I find interesting is that in all of you can see the influence of pulp. I think that’s what drove Gygax in many ways, and that’s what we see in Appendix N.

What I find fascinating about the initial vision of the game is that improvisation is built into the rule book.

JP: Definitely, if you look at the very earliest version of the rules, you see, you’re being instructed to devise your own dungeon, right? Devise your own world, your own situations. This eventually transitioned into a more authorial thing. I think to your point, a lot of the newer players today will play new adventures with a prescribed story arc.

PB: What I find fascinating about the initial vision of the game is that improvisation is built into the rule book. You didn’t need an authored world or campaign with various tiers of conspiracies to get the characters to take part in a dungeon crawl.

JP: The interesting thing about looking at D&D through the influences of fantasy fiction that inspired it is you begin to understand the relationship between those fictions and the kind of stories you might experience while playing. But of course, as you point out in your book, there were various lists of inspirational reading for D&D, and you examine those different sources in your book.

PB: Yes. What I’ve tried to do in my “Appendix N,” is not to dive too deep into one specific list and bring together stuff I knew Gygax must have been aware of, and for whatever reason didn’t include in his appendix but still feel like they’re a part of that zeitgeist.

JP: As you say, it is your own Appendix N, and you make that clear. As I read or re-read the stories in your book I was astonished by the thematic unity across them. As a curated selection there’s a lot of things that these stories have in common. For example, many of the stories are about a wandering adventurer who shows up in a town and the town has a problem. Almost like a Western. Maybe you could talk a bit about how you made the selections you did for the book?

PB: Sure. As soon as I started to think about putting together this appendix and I realized there would be restrictions. I began by looking at what was actually in Gygax’s list; first of all, there were things that I couldn’t get the rights for, for whatever reason, and that limits you in many ways too.

Secondly, a great number of the references are novels. I didn’t want to extract sections of novels because I don’t think it’s interesting for readers. It starts to read like a sampler rather than a nice collection. I wanted to make sure that even if you don’t know anything about D&D you could still enjoy these stories.

I also found that there would be authors that Gygax would mention but it would be works of theirs that I thought weren’t quite the story that captured the spirit of D&D perhaps. I wanted to see if I could find other stories by those same authors. And here I want to give a shout-out to the internet fiction database. Yes. Thank you. The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. That website is what the web is supposed to be for. You can look up an author, and the website will show you any of their stories. It will list every place that story has appeared, and it will have the cover art for every place in which that story appeared. Using that website, I was able to find stories by authors that appeared in pulp magazines.

Given all those limitations, I realized, in the end, this was going to be my Appendix N. What does D&D feel like for me? For me, it feels more like Conan than Tolkien, for example. I wanted to make something that felt a little pulpier, a little weirder, a little more like what the 70s felt like.

JP: Definitely. Anyone who knows your previous work (of which I’m a great admirer) like “Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll” knows how much you’ve tapped into that 70s zeitgeist, of Zeppelin and Bowie. It’s the kind of collection I would have expected you to curate, in a good way.

PB: Thank you. I think everybody has their own Appendix N. We all have those texts, as gamers in particular, that help us create worlds. We’re absolutely influenced in many ways, by the movies we’ve seen, the books and comics that we’ve read. What Gygax did was give permission to D&D players to curate their own stories for their own experiences with D&D. But at the same time, despite how personal it is, I hope it still honors Gygax’s original list.

I wanted to make something that felt a little pulpier, a little weirder, a little more like what the 70s felt like.

JP: Definitely, I think it is. I also think it’s good to acknowledge that sometimes Gygax isn’t as straightforward as he should be about some of his influences. You alluded to Tolkien there and he is a big part of the origins of D&D. But Gygax had a particular kind of (perhaps love/hate) relationship to Tolkien.

PB: Yeah, it’s really something.

JP: One thing that seems salient here is that a lot of these heroic fantasy stories are about single adventurers, which isn’t usually how you play D&D. Generally, you’re in a group and a lot of people attribute that group structure to The Fellowship of the Ring.

PB: Sure, and that structure is similar to the kind of pragmatic friendships that you assume your party has to maintain, while you’re playing D&D. You can get along well enough to work together, right. Even if you may not agree 100 percent with somebody else’s palette.

JP: I wanted to ask about the order you chose for the stories in the book. I’m like a super pedantic historian and would have probably done them in chronological order, partly because I’d want to show what was pre- and post-D&D. But I’m interested why you decided to order the stories in the way you have?

PB: Yes. Well, I chose in the order I did with a couple of considerations in mind. The first is there are three fairly long stories in here and I wanted to make sure that those were not too close together in the book so I decided to use those as the frame. I wanted the book to feel as though it were building up to these Epic tales. Something else that informed my thinking was the idea of envisioning the book as a dungeon crawl. We devised a map that is in the front and back that spreads out into a full map. If you look at the table of contents each story corresponds to a room in the dungeon that you’d be exploring. I decided it could be fun to navigate these stories as if you were playing a D&D module.

JP: It’s interesting too that after D&D came out there were attempts to do fiction that was explicitly based on the experience of playing D&D. I guess because I study it so much, I think of the release of D&D as a seminal moment when all these creative forces are unleashed. But I do think it had a profound influence on the way people approached fantasy.

PB: Absolutely. And you start to see that in the later additions of Dragon Magazine. The earliest stories were more general fantasy fiction, right? But the later stories really seem to be trying to capture a D&D-like experience.

JP: Definitely. I’m also interested in the authors who knew each other and how the things that they wrote were connected, any universities that were shared. HP Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith are the go-to reference point any time we look at D&D and the collaborative authorship that goes into creating stories. Critics have drawn parallels between a shared universe that is inhabited by a few of the authors and the process of storytelling in role-playing games. But yeah, I’m glad you included Clark Ashton Smith. Can you talk about the shared universe that Lovecraft was perhaps one of the first to articulate?

PB: Yeah, I mean, so, Lovecraft devised the notion of a universe populated by these anti-deities, which we called Old Ones. Lovecraft had a long-standing friendship with Robert E. Howard, and if I remember correctly, they had this idea that Howard might in fact have a story that exists in the same world that the Old Ones populate. And similarly, he would have a relationship like that with Clark Ashton Smith — who I personally think is the better of all three of them but that’s a different debate!

So anyway, these writers created a shared world, which is referred to as the Cthulhu Mythos. Although I don’t think Lovecraft ever called his world the mythos until other authors started playing in that sandbox.

JP: And maybe the sandboxes of D&D are similarly kind of these collaborative sandboxes that we all participate in.

On a slightly different topic, I was very pleased to see you’d included just a little bit of comics. And in the introduction, you hinted that if there were to be a sequel to this book, perhaps you could do something solely focused on comics? Where do you see comics in all of this, because obviously they had an enormous influence?

PB: Right. Certainly, an enormous influence. Also I think that would begin to reveal the influence of D&D on popular culture more broadly. So I do tease the idea of an Appendix N². I think that would have to include some of the best fantasy collections from the time. There’s a bunch of wonderful tales and excerpts from comics and things that I think could be fun.

JP: I mean, so much of it comes over directly. Obviously, there are the Conan books by Roy Thomas. I mean, rights for those might be difficult to secure at this point.

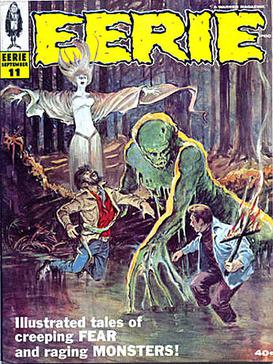

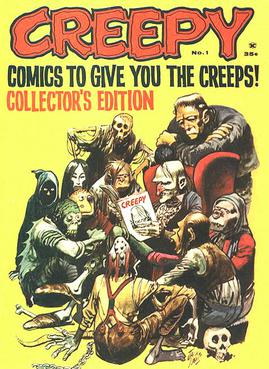

PB: Yes. But there’s also some great stories from “Creepy” and “Eerie” which were a part of that. And again, some of the stories in these comics first appeared in fanzines. There’s the fanzine culture happening at that time too, which could provide some really wonderful things to include.

JP: Yeah. I remember even in “Season of the Witch” I think you alluded to “Creepy” and “Eerie.” Again, just giving people the broader context of this, it was impossible to look at any of these things in isolation, the web of influences that surround them, that culturally influenced them at the time, is so immense. I’m sure you could do a whole other version about the musical influences.

PB: Absolutely. Yes. An album version would be very interesting.

Also, I would love to know if you’ve thought about this (and maybe we could end on this) but how much do you feel that the context to all of this is the 1970s. How much do you think D&D is a product of the 70s? It couldn’t have happened in another decade.

JP: I mean, there’s, there’s a number of reasons why that’s true. Yes.

The popularity of Tolkien was essential to it, I think. At that time Tolkien had reached number one bestseller on the New York Times list.

You also have the cultural forces of the 60s (the idealism, medievalism, and agrarianism) that helped popularize it. In the Bay Area especially the SCA were early adopters of D&D and helped define the reception of the game and steer it in directions that maybe the folks in Lake Geneva wouldn’t have intended.

PB: Right. Because the folks in Lake Geneva were still thinking about war gamers.

JP: Exactly. I totally agreed. You need a bit of that 60s idealism and you need it’s crash. You need Vietnam. You see a desire for the (unfortunately reductive) good versus evil stories that was so lacking in the perception of the American intervention in Vietnam, right? That escapist fantasy was absolutely essential to the reception of D&D.

PB: Definitely. Perhaps we should leave it there for today.

JP: Thanks so much for coming on Peter, we should talk more.

PB: Thank you too.